Introduction

Invasive breast cancer will be diagnosed in an estimated 300,000 American women in 2023.1 Early screening and targeted treatment have improved overall survival since the late 1980s,2 but breast cancer remains the second most common cause of cancer death in women, occurring in 1 in 39 women.1 Globally, premenopausal women account for approximately 20% of all new breast cancer diagnoses, and approximately 4% of breast cancer deaths occur in premenopausal women.3 This newsletter will focus on best practices for managing premenopausal women with breast cancer.

Breast cancers are classified by their molecular characteristics, specifically hormone receptor (HR) and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) subtyping, which influence presentation, prognosis, and appropriate therapeutic approaches.2 Hormone receptor-positive (HR+) breast cancer is more likely to grow in response to estrogen and progesterone and is more likely to respond to hormonal therapies. HR+ cancers account for 78% of all breast cancers (68% are HR+/HER2-, 10% are HR+/HER2+).2

Treatment for HR+/HER2‐ early-stage premenopausal breast cancer can include surgery, radiation, and systemic therapies.4 Systemic therapy can be administered either before surgery (neoadjuvant) or after surgery (adjuvant). Conventional systemic therapy includes tamoxifen, which is typically combined with ovarian function suppression (OFS) or an aromatase inhibitor (AI) combined with OFS. Chemotherapy is administered as needed based on the molecular profile of the tumor, and targeted therapies, including cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 (CDK4/6) inhibitors or poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors, may also be appropriate based on factors such as high-risk disease and gene mutations. In advanced unresectable and metastatic HR+/HER2‐ breast cancer, the addition of a CDK4/6 inhibitor to OFS and endocrine therapy has become the standard of care. Chemotherapy and antibody–drug conjugates are utilized once first-line options have been exhausted.

Use of Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH) agonist Therapy for Ovarian Suppression in Premenopausal ER+ Breast Cancer

Mohammed A. Jaloudi, MD

When discussing OFS with patients, I explain that surgical oophorectomy is permanent and cannot be reversed; therefore, the side effects are permanent. Using a GnRH agonist for OFS is transient, and we expect that some of the side effects will improve once we stop the medication.

Emily M. Beard, RN, BSN, OCN®, CBCN®

Shared decision-making is the key when discussing OFS options. Each patient comes to us with their own overall health and wellbeing goals that are not necessarily connected to treatment. As part of this process, we need to consider aspects such as their current quality of life, age, reproductive health, and family-building goals.

The effects of OFS on breast cancer recurrence and survival have been well-studied. A meta-analysis of these data was recently presented at the 2023 American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Annual Meeting.5 Of the nearly 15,000 premenopausal women enrolled in 25 studies, the 15-year risk of recurrence and death from breast cancer in women under the age of 45 was found to be reduced in those receiving ovarian ablation or suppression.

Various mechanisms exist to suppress ovarian function in women with premenopausal HR+ breast cancer, including surgical ovarian ablation (oophorectomy),6 radiation-induced ovarian ablation,7 and chemically-induced ovarian ablation via GnRH agonist therapy.8 However, GnRH agonist therapy has become the recommended option as surgical oophorectomy and radiation-induced ablation are irreversible,9 with key studies such as the Zoladex in Premenopausal Patients (ZIPP) trial, the Suppression of Ovarian Function Trial (SOFT), and Tamoxifen and Exemestane Trial (TEXT) evaluating GnRH agonist therapy.

The ZIPP trial was a long-term outcomes study designed to determine the effectiveness of adjuvant goserelin in premenopausal women with early breast cancer.10 Patients were randomly assigned to receive goserelin alone, tamoxifen alone, both treatments, or no treatment for a period of 2 years following appropriate primary therapy (surgery with or without radiotherapy and adjuvant systemic chemotherapy, where appropriate). Goserelin was associated with a risk reduction in all 4 study end points, including the risk of having an event-free survival (EFS), risk of recurrence, breast cancer mortality, and overall mortality. These effects were highly dependent on whether patients received tamoxifen. In groups that did not receive tamoxifen, goserelin was associated with a 33% reduction in EFS, a 34% reduction in risk of recurrence, a 29% reduction in risk of breast cancer mortality, and a 29% reduction in risk of overall mortality. In those patients who received tamoxifen, the benefit attributable to goserelin was smaller (8% reduction in EFS, 9% reduction in risk of recurrence, 11% reduction in breast cancer mortality, and 10% reduction in risk of overall mortality). The effect of goserelin was greatest in women who were node-negative and those with HR+ cancer, and the data were consistent with the observations that the benefits of goserelin may be greater in young women who had received prior chemotherapy.

The meta-analysis presented by Gray and colleagues at ASCO 2023 showed that the 15-year risk of recurrence and death from breast cancer in women under 45 years of age was reduced in those receiving ovarian ablation or suppression.

The SOFT study examined OFS (triptorelin, bilateral oophorectomy, or ovarian radiation) plus exemestane, OFS plus tamoxifen, or tamoxifen alone in premenopausal women diagnosed with HR+ breast cancer.11 The TEXT trial examined OFS (triptorelin, a gonadotropin-releasing hormone [GnRH] agonist; bilateral oophorectomy; or ovarian irradiation) in conjunction with the aromatase inhibitor (AI), exemestane, or tamoxifen in premenopausal women diagnosed with HR+ breast cancer.11 Combined analysis of data from SOFT and TEXT showed that adjuvant exemestane plus ovarian suppression significantly improved disease-free survival (DFS) and lengthened patients’ time without breast cancer. It also lengthened the time before distant recurrence compared with tamoxifen plus ovarian suppression. Additional analysis of these study cohorts showed that although patients at lowest risk of cancer recurrence saw minimal benefit from exemestane plus ovarian suppression, patients with high recurrence risk saw a benefit of 10% to 15% in freedom from breast cancer at 5 years.

FDA-approved GnRH Agonist Therapy Options for Premenopausal ER+ Breast Cancer

Mohammed A. Jaloudi, MD

In the US, goserelin is the only FDA-approved OFS agent for breast cancer and has a long, proven history of reliability and efficacy and it is still my standard. Could we use other OFS drugs? Perhaps. Should we? I don’t in my practice. If the medication doesn’t have indications or clinical trials based on breast cancer use, I don’t think we should be using it. I tend to stick to what the FDA and treatment guidelines tell me until there are approvals for other agents.

Abbey J. Kaler, MS, APRN, FNP-C

In my experience, the consistency of response physicians and nurses see in real-world use leads cancer treatment teams to choose goserelin as the OFS agent of choice for their patients.

Goserelin is the first and only GnRH agonist approved by the US Food and Drug administration (FDA) for the treatment of premenopausal breast cancer. The FDA approved goserelin (3.6 mg for the palliative treatment of advanced breast cancer in pre- and perimenopausal women in 1995).12,13 Goserelin reduces circulating concentrations of estrogen in the body through interference with the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis.14 It is a ready-to-use implant administered subcutaneously every 28 days.

FDA approval of goserelin for breast cancer was based on the SWOG-8692 study, which commenced in the late 1980s. This was a prospective, randomized clinical study in premenopausal women with metastatic HR+ breast cancer to establish the use of goserelin as a reversible OFS treatment. Goserelin was compared to oophorectomy and showed that goserelin resulted in decreased estradiol, luteinizing hormone, and follicle stimulating hormone, indicating a postmenopausal state, which led to failure-free survival and overall survival (OS) rates comparable to surgical ovariectomy.15 This early work established goserelin as a viable therapeutic option, allowing patients and their physicians to make an informed decision between permanent surgical ovarian suppression and a reversible, non-invasive drug therapy option in the treatment of their breast cancer.

Goserelin is the first and only GnRH agonist approved by the FDA. The goserelin 3.6 mg implant is indicated for the palliative treatment of advanced breast cancer in pre- and perimenopausal women.

Goserelin has subsequently been studied in numerous clinical trials over a span of nearly 40 years and is included as standard OFS treatment in studies for other cancer drugs. In searching ClinicalTrials.gov on December 8, 2023, and using the terms “breast cancer” and “goserelin”, 135 breast cancer studies that included goserelin were found to be registered. Of the 135 studies, 20 studies were active but not recruiting, and 30 were recruiting patients. Furthermore, a PubMed® search on December 8, 2023, using the terms “(goserelin) AND (evaluation of breast cancer)”, yielded 90 publications. Among recent phase 3 data published are MONALEESA-716 and NATALEE17, which examined the function of the CDK4/6 inhibitor, ribociclib, in conjunction with endocrine therapy to treat breast cancer in younger, premenopausal patients. In these trials, goserelin was administered to suppress ovarian function in conjunction with endocrine therapy (either tamoxifen or an AI).

Timing and Duration of OFS Therapy in Premenopausal ER+ Breast Cancer

Mohammed A. Jaloudi, MD

I tend to start OFS upfront with initiation of chemotherapy. I think there’s more benefit to it and it just makes more sense. If it’s hormone positive breast cancer, I would like to give OFS to patients for 5 years if possible based on some of the clinical trials, including the recent ASTRRA trial.

Emily M. Beard, RN, BSN, OCN®, CBCN®

Our oncologists like to share the SOFT and TEXT data, especially with our younger patients. Those 2 trials really have great evidence over 20-plus years of follow-up treatment showing the benefit of extended treatment. We really do encourage that 5-year goal and addressing individual symptoms related to OFS helps patients reach that goal.

The optimal use and timing of OFS, whether medical or surgical, is a shared decision between patients and their medical team. Treatment plans and approaches must be tailored to an individual patient’s risk of cancer recurrence, reproductive goals, and comorbidities, as well as social and financial factors.18

While guidance on when to initiate OFS treatments remains fluid and can occur before, with, or after chemotherapy,19–23 randomized trials have demonstrated that GnRH agonists protect against ovarian failure and premature ovarian insufficiency when administered in parallel24 or prior to chemotherapy.21,22,25 Safety data also support the administration of GnRH agonists prior to or in conjunction with chemotherapy.22,25 These medications may also be initiated after chemotherapy in patients who remain premenopausal;23 however, meta-analyses examining GnRH agonists in breast cancer showed OFS was usually initiated 1 to 2 weeks prior to chemotherapy start and continued alongside other treatments.26

Furthermore, premenopausal patients may benefit from achieving amenorrhea if a GnRH agonist is incorporated before or with chemotherapy, as evidence suggests that chemotherapy-induced amenorrhea (CIA) is associated with improved outcomes in young patients with HR+ breast cancer. In a meta-analysis of 13 studies, premenopausal women with ER+ breast cancer and CIA had a significantly improved prognosis versus participants without CIA, irrespective of various factors.27 However, the rate of CIA varies based on age and chemotherapy regimen. A retrospective study of 305 patients treated with anthracycline regimens, with or without taxanes, in the adjuvant or neoadjuvant setting found that nearly 50% of the 74 patients who were aged <40 years did not achieve CIA versus 29.2% of patients 40 to 45 years and 4.9% of those >45 years.28 This suggests that premenopausal patients could benefit from the addition of a GnRH agonist before or with chemotherapy to reduce estradiol levels and ensure an amenorrheic status. In the OPTION study, patients who received goserelin with chemotherapy had lower FSH, LH, and estradiol levels versus chemotherapy alone during chemotherapy, at the end of chemotherapy, and 12 months post-chemotherapy treatment.29

When considering duration of therapy, treatment plans and approaches must be tailored.18 The ASCO Clinical Practice Guideline Update on Ovarian Suppression recommends that higher-risk premenopausal women with HR+ metastatic breast cancer be offered ovarian suppression for a duration of 5 years in combination with hormone therapy.9 Adjuvant endocrine therapy, in general, is recommended for a minimum of 5 years, with data showing that longer treatment improves DFS.20

The recommended 5-year duration of OFS is largely based on the results of the TEXT/SOFT trials,11,19 but other studies have also examined duration of OFS. Initial data from the Addition of Ovarian Suppression to Tamoxifen in Young Women With Hormone-Sensitive Breast Cancer Who Remain Premenopausal or Regain Vaginal Bleeding After Chemotherapy (ASTRRA) trial demonstrated that 2 years of goserelin added to tamoxifen in an adjuvant setting significantly increased DFS and OS compared to tamoxifen alone in patients who remained premenopausal after completing chemotherapy after a median follow-up of 63 months.30 Long-term follow-up indicated that treatment with OFS plus tamoxifen provided consistent benefit in DFS, yielding a significantly higher DFS rate of 85.4% versus 80.2% in the tamoxifen alone group at 8 years, but OS did not remain statistically different.30 With consistent DFS benefits after long-term follow-up, the results of ASTRRA concluded that adding 2 years of OFS to tamoxifen should be considered in patients who remain in a premenopausal state or resume ovarian function after treatment with chemotherapy.

For patients who are unable to remain on OFS therapy for the recommended 5 years, studies have demonstrated that at least 2 years of treatment provides clinical benefit.

In addition, the ZIPP study, as mentioned earlier, also demonstrated that 2 years of goserelin therapy resulted in a 29% reduction in both risk of breast cancer mortality and overall mortality.10 For patients who are unable to remain on therapy for 5 years, these studies provide evidence that at least 2 years of treatment with goserelin provides clinical benefit.

Ovarian Preservation and the Role of GnRH Agonist Therapy in Premenopausal ER+ Breast Cancer

Mohammed A. Jaloudi, MD

For younger patients, I introduce temporary OFS as a means of ovarian preservation. Trials have shown that adding OFS in premenopausal women increases the likelihood of return of ovarian function after completion of their treatment.

Preserving fertility is an important concern for many premenopausal women diagnosed with breast cancer who require chemotherapy. Recent data from the Prevention of Early Menopause Study (POEMS) and Prevention of Menopause Induced by Chemotherapy: A Study in Early Breast Cancer Patients—Gruppo Italiano Mammella 6 (PROMISE-GIM6) trials provide evidence that adding a GnRH agonist to chemotherapy can help protect ovarian function and increase pregnancy rates in these patients without negatively impacting survival outcomes.25,31

The POEMS study evaluated long-term pregnancy and disease outcomes in premenopausal women with stage I-IIIA estrogen/progesterone receptor-negative breast cancer treated with chemotherapy with or without goserelin.31 Patients randomized to chemotherapy plus goserelin were more likely to report ≥1 pregnancy when compared with the chemotherapy alone group at 5 years (23.1% vs 12.2%, respectively). The addition of goserelin to chemotherapy was associated with improved but not statistically significant DFS and OS.31 This long-term analysis of ER/PR negative breast cancer found continued evidence that goserelin plus chemotherapy not only helps patients avoid premature menopause, but also increases pregnancy rates without adverse effects on breast cancer outcomes.

The PROMISE-GIM6 phase 3 trial evaluated the long-term safety and efficacy of the GnRH agonist triptorelin combined with chemotherapy to preserve ovarian function in premenopausal patients with early breast cancer.25 After a median 12.4 years of follow-up, there were no differences in 12-year DFS or OS between the GnRH agonist and chemotherapy-alone groups, including in the 80% of patients with hormone receptor-positive disease. A total of 9 patients in the GnRH agonist arm had a post-treatment pregnancy compared with 4 in the control arm. These results provide reassuring evidence that using a GnRH agonist with chemotherapy is a safe strategy to preserve ovarian function without negatively impacting outcomes, even in patients with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer.

In the OPTION study, 202 premenopausal patients who received adjuvant or neoadjuvant chemotherapy were randomized to chemotherapy alone or goserelin before and during chemotherapy. The protective effect of goserelin was assessed by the incidence of premature ovarian insufficiency (POI), defined as amenorrhea with elevated FSH with a cutoff of 25 IU/L. The prevalence of POI in the goserelin group was 18.5% versus 34.8% in the control group (P=0.048).29

These studies demonstrate that fertility preservation strategies can be safely incorporated into breast cancer treatment plans for those wishing to achieve pregnancy after therapy. Guidelines recommend that clinicians have discussions with all patients of childbearing potential regarding fertility preservation options before starting systemic therapy,32 and they suggest that while GnRH agonists may protect ovarian function, other fertility preservation modalities should still be pursued in young adult women.32 Patients who wish to have children after completing their cancer treatment should be referred to a fertility specialist for consultation.32

Managing Side Effects of GnRH Agonist Therapy in Breast Cancer

Emily M. Beard, RN, BSN, OCN®, CBCN®

It is important for us to prepare patients for the potential sudden onset of side effects from medical menopause with goserelin, including hot flashes, sleep issues, and sexual dysfunction. Although not every patient experiences all side effects, making them aware of what may occur and that there are many options for symptom management is crucial. We also need to understand the value of a multidisciplinary approach, including referrals to behavioral health for counseling on things like mindfulness and communication, sex therapists, pelvic floor physical therapy, and nutritionists for bone health. Normalizing open conversations about sexual health and encouraging patients not to suffer in silence are also key. We should also be consistently screening patients for depression and emotional distress throughout treatment using validated tools, as this population is at increased risk for mental health effects. Assuming patients are doing well and overlooking their holistic needs beyond just their medical treatment can be detrimental.

Abbey J. Kaler, MS, APRN, FNP-C

It’s important to have open conversations with patients about the need for OFS to enable optimal therapy. We should consider basic interventions for managing side effects, such as staying hydrated, dressing lightly, decreasing caffeine, and optimizing diet. Adding in things like acupuncture, yoga, meditation, and low-dose antidepressants can also help if needed. I also recommend the routine use of an assessment tool to screen patients every 30 days for distress levels and issues like nutrition, physical therapy, safety, and suicidal ideation. For us, scores of 4+ automatically trigger a social work consult. In addition, regular holistic check-ins with patients throughout treatment should be emphasized.

Mohammed A. Jaloudi, MD

I would recommend routinely screening patients on endocrine therapy with bone density scans every 2 years and starting bisphosphonates or denosumab if osteopenia/osteoporosis is found. Overall, I recommend close follow-up and monitoring for side effects in patients on long-term endocrine therapies, with a low threshold to intervene medically or with referrals as needed.

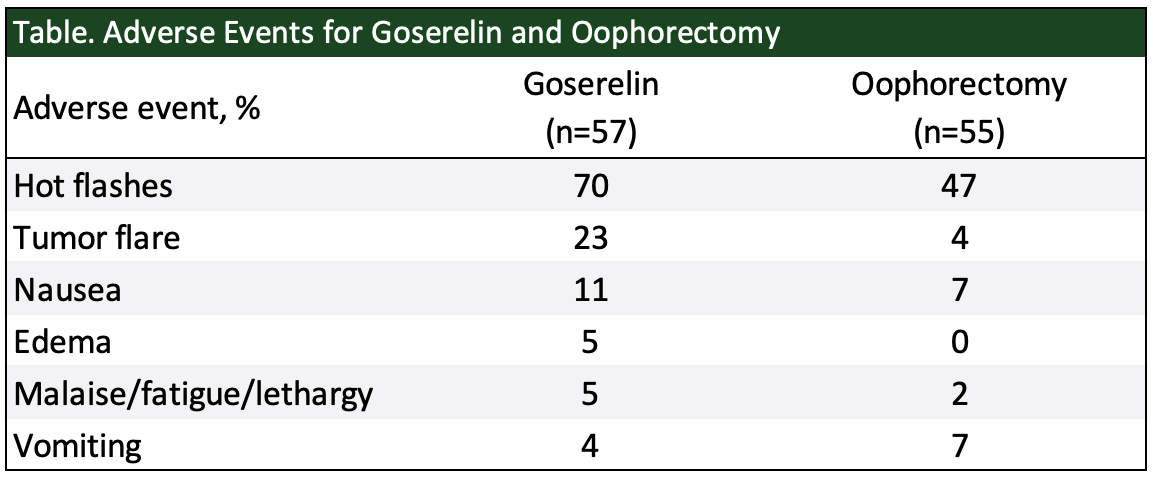

The most common adverse events (>20%) for women treated with goserelin are hot flashes, headache, sweating, acne, emotional lability, depression, decreased libido, vaginitis, breast atrophy, seborrhea, and peripheral edema.33 In the goserelin phase 2 clinical trial program, among 333 pre- and perimenopausal women with advanced breast cancer, hot flashes occurred in 75.9% and decreased libido in 47.7% – reflecting the hormone-suppressing actions of goserelin.33 Goserelin has also been compared with oophorectomy in pre- and perimenopausal women with advanced breast cancer in a controlled clinical trial.33 The table below shows the adverse events that were reported at a frequency of ≥5%.

Goserelin has also been associated with loss of bone mineral density (BMD). After 6 months of treatment, 109 women showed an average 4.3% decrease in vertebral trabecular BMD compared with pretreatment.33 Of these, 66 were reassessed at 6 months post-treatment, showing an average 2.4% BMD loss. At 12 months, 28 patients had an average 2.5% decrease versus pretreatment. These findings suggest that bone changes may be partially reversible after discontinuing goserelin.33

Despite the side effects associated with OFS, more than 60% of women were adherent to their OFS regimen in a recent real-world study. Among women who initially began a GnRH analog, more than 40% eventually underwent oophorectomy, resulting in significantly more hot flashes (74% vs 48%, P< .001), arthralgias (46% vs 30%, P= .003), and vaginal dryness (37% vs 21%, P= .001) compared with patients remaining on GnRHa.34 Similarly, another study showed that patients taking tamoxifen plus OFS had an adherence rate of approximately 60% versus those taking tamoxifen alone, who had an adherence rate of approximately 50%, suggesting the likelihood of adherence was similar regardless of OFS exposure.35

Although there is a lack of evidence-based guidelines for managing the full sequelae of symptoms associated with medication-induced menopause, interventions are available and can be tailored to the unique needs of each patient.36 Pharmacological interventions, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, gabapentin, and clonidine, as well as nonpharmacological interventions, such as cognitive behavioral therapy and mind-body therapies, can be used to effectively address vasomotor symptoms.36 Vulvovaginal symptoms and dyspareunia can be managed with nonhormonal vaginal moisturizers, lubricants, low-dose topical hormone therapies, and pelvic floor physical therapy. Lifestyle modifications such as physical activity, smoking cessation, reduced alcohol intake, healthy nutrition, and maintaining a healthy weight are important to many components of menopausal symptom management. Finally, psychosocial support may be necessary for feelings of distress, uncertainty, isolation, and loneliness. Because of medication-induced menopause with OFS, patient education and encouraging open communication are critical. It is also important to develop both monitoring and treatment strategies to assess and manage side effects and minimize their impact on patients’ quality of life.

Administration of GnRH Agonist Therapy

Emily M. Beard, RN, BSN, OCN®, CBCN®

The goserelin injection is generally well-tolerated with proper positioning of the patient and by providing reassurance and instructing them to avoid looking at the needle. Local anesthetic can be made available, especially for highly apprehensive patients undergoing their first injection, but it is not typically needed for most patients. After the first injection without local anesthetic, many patients realize it is not as bad as anticipated. The key is making patients feel comfortable and addressing any fears they have. After administering goserelin a couple times and getting familiar with the procedure, it is no more difficult than other depot injections. Ultimately, it comes down to patient preference and motivation, as well as provider recommendations. Offering a topical anesthetic as an option can help ease needle anxiety for those who really need it. But most patients can manage the injection without anesthesia once positioned properly and reassured.

Abbey J. Kaler, MS, APRN, FNP-C

Going back to basics helps when dealing with injections – letting patients look away or utilizing distraction. Some patients fear all needles, regardless of size; therefore, most of us are proficient with the use of lidocaine-prilocaine cream or our local numbing cream of choice. Through education, patients can learn their preferences for managing injections and optimizing comfort. Key points are educating patients about options and working together for best results. In addition, we need to use caution with low BMI patients to ensure adequate subcutaneous tissue for safe injection. Being well-educated on proper site selection, we can typically identify an appropriate location for injection.

The goserelin 3.6-mg dose should be administered every 28 days subcutaneously.33 Position the patient comfortably with the upper body slightly elevated. Cleanse the anterior abdominal area below the navel with an alcohol swab. Holding the protective sleeve, pinch the skin of the abdominal wall below the navel using an aseptic technique and insert the beveled needle at a 30 to 45-degree angle in 1 steady motion until the protective sleeve touches the skin.33 To administer goserelin and activate the sleeve, grasp the barrel and fully depress the plunger. A click indicates the sleeve is covering the needle. Withdraw the needle, allowing the sleeve to slide over it and discard the syringe appropriately.33

When inserting the needle, it is important to avoid penetrating muscle or peritoneum. Caution should also be used when injecting into the anterior abdominal wall due to the underlying inferior epigastric artery. If blood appears in the syringe, withdraw it and inject elsewhere with a new syringe. Patients should be monitored for signs of abdominal hemorrhage.33 Extra precautions should be taken when giving goserelin to patients with low body mass index (BMI) or on full-dose anticoagulants.

The administration of goserelin has been studied in a number of settings. A randomized crossover study ascertained nurses’ administration time and perceptions of the injection systems of 2 GnRH agonist treatments (goserelin and leuprorelin).37 In data analyzed from 82 nurses, significantly more nurses agreed that compared with leuprorelin, goserelin was easy to prepare prior to administration (91% versus 61%; P<0.001); there were good safety precautions with this preparation (85% versus 40%; P<0.001), and the equipment was easy to manipulate (76% versus 64%; P<0.001). Furthermore, the system used to administer the goserelin implant was significantly quicker to prepare and deliver than the vial system of the comparator GnRH agonist product.

A second study focused on whether needle size influences a patients’ perception of pain on administration of a GnRH agonist.38 A total of 24 blindfolded patients received 2 injections of goserelin and 26 blindfolded patients received 2 injections of leuprorelin. Pain of injection on a visual analogue scale (VAS) ranging from 0 (no discomfort) to 100 (maximum discomfort) for the first injection was a median 5 and 3 for goserelin and leuprorelin, respectively (P=0.162). For the second injection, median pain scores were 7 and 2.5 for goserelin and leuprorelin, respectively (P=0.064), indicating no significant difference between the pain levels experienced.

The Future of OFS and GnRH Agonist Therapy

Optimizing and individualizing OFS treatment of premenopausal women with HR+ breast cancer remains a key area of research. As clinical trials to support the use of OFS in premenopausal women with HR+ breast cancer were conducted prior to the use of genomic assays, taxane- and anthracycline-based chemotherapy, and targeted therapies, additional research and clinical trials are ongoing to further elucidate which populations might benefit the most from OFS. The OFSET trial is a much-awaited study of adjuvant chemotherapy, OFS (goserelin, triptorelin, or leuprolide per investigator discretion), and endocrine therapy versus OFS and endocrine therapy in premenopausal women with early-stage HR+ breast cancer (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT05879926). Investigators will provide the long-awaited answer of whether moderate risk patients, based on risk of recurrence scores, can completely avoid chemotherapy based on the clinical benefit of ovarian suppression and endocrine therapy alone.

Additionally, many treatments for breast cancer negatively affect ovarian function, which can lead to long-term adverse health effects. Remarkably, fewer than 10% of phase 3 breast cancer trials have examined the impact of treatments on ovarian function.39 As there is a substantial gap in information to inform shared decision-making between healthcare providers and patients, ASCO has issued a statement regarding the incorporation of measures of ovarian toxicity into all clinical trials of anticancer agents intended for cure or primary prevention in premenopausal women.40 ASCO also suggests collection of ovarian toxicity measures at baseline and 12 to 24 months following treatment cessation as a minimum, as well as assessment of clinical measures and biomarkers of ovarian function.

A survey by Dibble and colleagues presented at SABCS 2023 showed that more than two-thirds of respondents stated they would consider OFS beyond 5 years if doing so would reduce their risk of breast cancer recurrence.

Extended ovarian suppression beyond 5 years has become a recent topic of interest and discussion of both breast cancer experts and patients. While some breast cancer experts believe treating high-risk patients beyond 5 years with therapy may be warranted, no data currently exist.41 A poster was presented at the 2023 San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium (SABCS) detailing the preferences of young breast cancer patients regarding OFS use beyond 5 years.42 Of the data analyzed from 615 patients, nearly 40% reported that their provider recommended to continue OFS for more than 5 years. Moreover, despite citing factors such as side effects (77.4%), inconvenience of injection visits (44.2%), and high cost of medication (36.3%), most respondents (64.4%) stated that they would consider OFS beyond 5 years if doing so would reduce their risk of breast cancer recurrence. As such, studying OFS for an extended duration provides a viable opportunity for future research.

In summary, overwhelming evidence exists establishing the clinical benefit of OFS in premenopausal women with ER+ breast cancer, with the recently presented meta-analysis at ASCO 2023 highlighting the importance of OFS in all premenopausal patients regardless of age. Additionally, starting OFS prior to or in conjunction with chemotherapy has demonstrated ovarian protection and the ability to prevent premature ovarian insufficiency. Ongoing and future studies will help answer important questions for both clinicians and patients on whether OFS with endocrine therapy may provide clinical benefit alone to reduce chemotherapy exposure to a broader group of patients and if extended OFS beyond 5 years may be warranted in high-risk patients.

References

- American Cancer Society. Cancer facts & figures 2023. Published 2023. Accessed December 12, 2023. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2023/2023-cancer-facts-and-figures.pdf

- American Cancer Society. Breast cancer facts & figures 2022-2024. Published 2022. Accessed December 12, 2023. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/breast-cancer-facts-and-figures/2022-2024-breast-cancer-fact-figures-acs.pdf

- Heer E, Harper A, Escandor N, et al. Global burden and trends in premenopausal and postmenopausal breast cancer: a population-based study. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8:e1027-e1037.

- Huppert LA, Gumusay O, Idossa D, Rugo HS. Systemic therapy for hormone receptor-positive/human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative early stage and metastatic breast cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 2023;73:480-515.

- Gray RG, Bradley R, Braybrooke J, et al. Effects of ovarian ablation or suppression on breast cancer recurrence and survival: Patient-level meta-analysis of 14,993 pre-menopausal women in 25 randomized trials. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41:503.

- Singh G. Oophorectomy in breast cancer-controversies and current status. Indian J Surg. 2012;74:210-212.

- Al Asiri M, Tunio MA, Abdulmoniem R. Is radiation-induced ovarian ablation in breast cancer an obsolete procedure? Results of a meta-analysis. Breast Cancer (Dove Med Press). 2016;8:109.

- Zhou J, Wu SG, Wang JJ, et al. Ovarian ablation using goserelin improves survival of premenopausal patients with stage II/III hormone receptor-positive breast cancer without chemotherapy-induced amenorrhea. Cancer Res Treat. 2015;47:55.

- Burstein HJ, Lacchetti C, Anderson H, et al. Adjuvant endocrine therapy for women with hormone receptor-positive breast Cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical practice guideline update on ovarian suppression. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:1689-1701.

- Hackshaw A, Baum M, Fornander T, et al. Long-term effectiveness of adjuvant goserelin in premenopausal women with early breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101.

- Regan MM, Francis PA, Pagani O, et al. Absolute benefit of adjuvant endocrine therapies for premenopausal women with hormone receptor-positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative early breast cancer: TEXT and SOFT Trials. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34.

- FDA. Zoladex (Goserelin Acetate Implant). Drugs@FDA. Published January 18, 2006. Accessed October 23, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/97/19726S018_Zoladex.cfm#:~:text=Approval%20Date%3A%206%2F27%2F1997

- The Pink Sheet. Zoladex breast cancer approval adds new indication to Zeneca’s fastest growing major product; phase IV study to come on relationship of drug to estradiol. Published 1996. Accessed December 12, 2023. https://pink.citeline.com/PS027440/ZOLADEX-BREAST-CANCER-APPROVAL-ADDS-NEW-INDICATION-TO-ZENECAs-FASTEST-GROWING-MAJOR-PRODUCT-PHASE-IV-STUDY-TO-COME-ON-RELATIONSHIP-OF-DRUG-TO-ESTRADIOL

- Jonat W. Goserelin (ZoladexTM) - its role in early breast cancer in pre- and perimenopausal women. Br J Cancer. 2001;85.

- Taylor CW, Green S, Dalton WS, et al. Multicenter randomized clinical trial of goserelin versus surgical ovariectomy in premenopausal patients with receptor-positive metastatic breast cancer: an intergroup study. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16.

- Lu YS, Im SA, Colleoni M, et al. Updated overall survival of ribociclib plus endocrine therapy versus endocrine therapy alone in pre- and perimenopausal patients with HR+/HER2- advanced breast cancer in MONALEESA-7: a phase III randomized clinical trial. Clin Cancer Res. 2022;28:851-859.

- Slamon DJ, Fasching PA, Hurvitz S, et al. Rationale and trial design of NATALEE: a phase III trial of adjuvant ribociclib + endocrine therapy versus endocrine therapy alone in patients with HR+/HER2− early breast cancer. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2023;15.

- Connolly RM, Miller KD. Back to the beginning: the role of ovarian suppression in management of hormone sensitive breast cancer in premenopausal women. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41.

- Pagani O, Regan MM, Walley BA, et al. Adjuvant exemestane with ovarian suppression in premenopausal breast cancer. New Engl J Med. 2014;371.

- Rugo HS, Rumble RB, Macrae E, et al. Endocrine therapy for hormone receptor-positive metastatic breast cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology Guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:3069-3103.

- Moore HCF, Unger JM, Phillips KA, et al. Goserelin for ovarian protection during breast-cancer adjuvant chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:923-932.

- Lambertini M, Boni L, Michelotti A, et al. Ovarian suppression with triptorelin during adjuvant breast cancer chemotherapy and long-term ovarian function, pregnancies, and disease-free survival: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;314:2632-2640.

- Kim HA, Lee JW, Nam SJ, et al. Adding ovarian suppression to tamoxifen for premenopausal breast cancer: A randomized phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:434-443.

- Blumenfeld Z, Evron A. Preserving fertility when choosing chemotherapy regimens - the role of gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2015;16:1009-1020.

- Lambertini M, Boni L, Michelotti A, et al. Long-term outcomes with pharmacological ovarian suppression during chemotherapy in premenopausal early breast cancer patients. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2022;114:400-408.

- Abdel-Razeq H. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists during chemotherapy for ovarian function and fertility preservation for patients with early-stage breast cancer. Cancer Manag Res. 2019;11.

- Zhou Q, Yin W, Du Y, et al. Prognostic impact of chemotherapy-induced amenorrhea on premenopausal breast cancer: a meta-analysis of the literature. Menopause. 2015;22:1091-1097.

- Pérez-Fidalgo JA, Roselló S, García-Garré E, et al. Incidence of chemotherapy-induced amenorrhea in hormone-sensitive breast cancer patients: the impact of addition of taxanes to anthracycline-based regimens. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;120:245-251.

- Leonard RCF, Adamson DJA, Bertelli G, et al. GnRH agonist for protection against ovarian toxicity during chemotherapy for early breast cancer: the Anglo Celtic Group OPTION trial. Ann Oncol. 2017;28:1811-1816.

- Baek SY, Noh WC, Ahn SH, et al. Adding ovarian suppression to tamoxifen for premenopausal women with hormone receptor–positive breast cancer after chemotherapy: an 8-year follow-up of the ASTRRA trial. J Clin Oncol. Published online 2023.

- Moore HCF, Unger JM, Phillips KA, et al. Final Analysis of the Prevention of Early Menopause Study (POEMS)/SWOG Intergroup S0230. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019;111:210-213.

- Oktay K, Harvey BE, Partridge AH, et al. Fertility preservation in patients with cancer: ASCO clinical practice guideline update. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2018;36:1994-2001.

- TerSera Pharmaceuticals. Zoladex (Goserelin Implant). Package Insert.; 2023.

- Sukumar JS, Quiroga D, Kassem M, et al. Patient preferences and adherence to adjuvant GnRH analogs among premenopausal women with hormone receptor positive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2021;190:183-188.

- Reeder-Hayes KE, Mayer SE, Lund JL. Adherence to endocrine therapy including ovarian suppression: A large observational cohort study of US women with early breast cancer. Cancer. 2021;127:1220-1227.

- Esch M, Schadewald DM. Treatment-induced ovarian insufficiency and early menopause in breast cancer survivors. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2023;27:7-12.

- Morgan G, Cooley C. Injection systems for two luteinising hormone-releasing hormone agonists: A comparative assessment of administration times and nurses’ perceptions. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2005;9:334-340.

- Montgomery BSI, Borwell JP, Higgins DM. Does needle size matter? Patient experience of luteinising hormone-releasing hormone analogue injection. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2005;8:66-68.

- American Society of Clinical Oncology. ASCO issues recommendations for assessing ovarian toxicity in cancer clinical trials. Accessed November 28, 2023. https://old-prod.asco.org/about-asco/press-center/news-releases/asco-issues-recommendations-assessing-ovarian-toxicity-cancer

- Cui W, Rocconi RP, Thota R, et al. Measuring ovarian toxicity in clinical trials: an American Society of Clinical Oncology research statement. Lancet Oncol. 2023;24:e415-e423.

- Buono G, Arpino G, Del Mastro L, et al. Extended adjuvant endocrine treatment for premenopausal women: A Delphi approach to guide clinical practice. Front Oncol. 2022;12:1032166.

- Dibble K, Sella T, Ruddy K, et al. Ovarian function suppression (OFS) use beyond five years? Young breast cancer patients preferences. In: San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium. PO4-01-11; 2023.