Palbociclib is a reversible small-molecule inhibitor of cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) signaling pathways 4 and 6.1 Through the inhibition of these kinases, palbociclib reduces downstream signaling that leads to the proliferation of hormone receptor–positive breast cancer cells.1

Initially approved by the US Food and Drug Administration under an accelerated approval pathway in 2015, palbociclib is a National Comprehensive Cancer Network preferred drug indicated for estrogen receptor (ER)- and/or progesterone receptor (PR)-positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-negative advanced or metastatic breast cancer in combination with an aromatase inhibitor for use in the first-line setting, or with fulvestrant in subsequent-line settings in patients whose disease has progressed after receiving endocrine therapy.2

The recommended standard dose of palbociclib is 125 mg orally once daily for 21 days, followed by 7 days off, which is then repeated every 28 days.1

The hematologic adverse events related to treatment with palbociclib include neutropenia, leukopenia, anemia, and thrombocytopenia, whereas the most common nonhematologic adverse events are infections, nausea, stomatitis, and fatigue.1 Palbociclib is extensively hepatically metabolized via cytochrome (CY)P3A and sulfotransferase 2A1 enzymes, but hepatotoxicity is not considered a major side effect of treatment.1 Although elevated liver function tests (LFTs) were reported in clinical trials of palbociclib, these occurrences were rare and often mild.3-6

In the PALOMA-1 study, which compared palbociclib and letrozole with letrozole alone, LFTs were elevated in 7.2% of patients who received palbociclib, with 1% of these patients having grade 3 aspartate aminotransferase (AST).3-5

In the PALOMA-2 study, which compared palbociclib and letrozole with letrozole and placebo, elevated all-grade AST and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) were reported in 9.7% and 9.9%, respectively, of patients in the palbociclib arm.1,5 Of these patients, only 3 (1%) required a dose reduction as a result of increased ALT.6

Last, in the PALOMA-3 study, which compared palbociclib and fulvestrant to fulvestrant and placebo, all-grade AST and ALT elevations were reported in 7.5% and 5.8%, respectively, of patients in the palbociclib arm.1,4 One patient in the palbociclib arm had grade 3 abnormal hepatic function and 1 patient had a fatal hepatic failure; however, it is unclear if these were drug-related or disease-related responses.7

No significant differences were found in any-grade AST and ALT elevations between the palbociclib and comparator arms across all 3 PALOMA studies, as was demonstrated by a final pooled safety analysis.8 However, grade 3 or 4 AST and ALT elevations occurred more frequently with palbociclib than with the comparator drugs (3.3% and 2.3% vs 1.9% and 0.2%, respectively).8

In addition, it is important to note that all 3 PALOMA studies included patients with liver metastases, which may also affect liver function,3,6,7 thus the number of patients who have true palbociclib-induced hepatotoxicity may be smaller.

Typically, treatment for drug-induced liver injury is dependent on the degree of liver damage and is composed of the discontinuation of the offending agent and supportive care as needed.9 For patients with mild-to-moderate hepatic impairment (defined as a Child-Pugh class A or B), no dose adjustment is necessary for palbociclib, but patients with severe impairment (Child-Pugh class C) may receive a reduced dose of 75 mg once daily for 21 days, followed by a 7-day break in treatment, for a total 28-day cycle.1

Patients who have grade ≥3 nonhematologic toxicity should delay treatment with palbociclib until their symptoms resolve to a lower grade and should then resume therapy at the next lower dose.1 The monitoring of complete blood count with differential before treatment initiation, every 2 weeks for the first 2 cycles, and then before each additional cycle is recommended, along with monitoring for the signs and symptoms of interstitial lung disease and infection. Periodic LFT monitoring, however, is not addressed in the prescribing information for palbociclib.1

This report presents the case of a patient with metastatic breast cancer and elevated AST and ALT that were primarily attributed to treatment with palbociclib.

Case Report

A 56-year-old postmenopausal woman had a medical history of long-standing asymptomatic multiple sclerosis that did not require medical intervention and no history of hepatitis or liver disease.

Beginning in December 2020, the patient underwent a bilateral mammogram that showed 2 masses, and a biopsy was performed. She had a 3.8-cm, grade 3, subareolar invasive ductal carcinoma that was 90% ER-positive, 30% PR-positive, and HER2-negative at 2+ intensity via immunohistochemistry (IHC) with a fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) result of 1.2. The second mass at the 10:00 axis was 98% ER-positive, 60% PR-positive, and HER2-negative at 2+ intensity via IHC (FISH, 1.0).

A right axillary lymph node biopsy demonstrated lymphoid tissue with metastatic breast carcinoma, and staging studies via computed tomography (CT) revealed a 1.5-cm sclerotic focus in the T10 vertebral body concerning for metastasis that was confirmed by biopsy to be a >90% ER-positive, >90% PR-positive, HER2-negative (IHC 1+) tumor, which is consistent with primary breast cancer.

The patient started treatment with anastrozole 1 mg daily on March 4, 2021, which she tolerated well. On May 28, 2021, the patient also began treatment with palbociclib 125 mg daily for 21 days, followed by 7 days off, which was repeated every 28 days, in addition to zoledronic acid 4 mg intravenously every 3 months for her osseous metastasis.

The patient’s other medications included cholecalciferol 1000 IU daily, ibuprofen 800 mg every 6 hours as needed for mild pain, and tramadol 50 mg every 6 hours as needed for moderate pain. Of note, the patient’s complementary medications also included a daily oral supplement of turkey tail mushroom supplement.

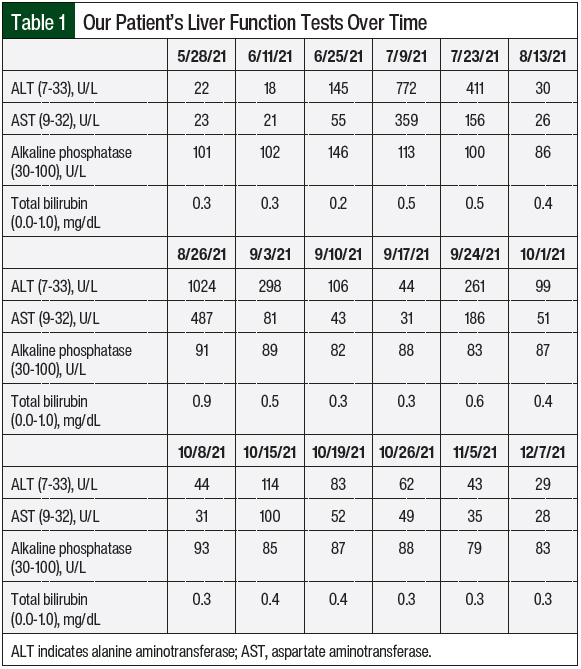

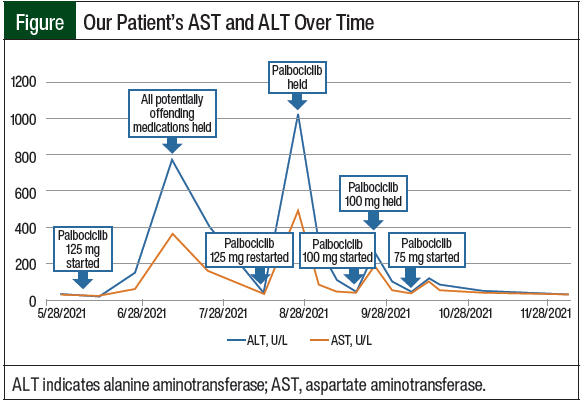

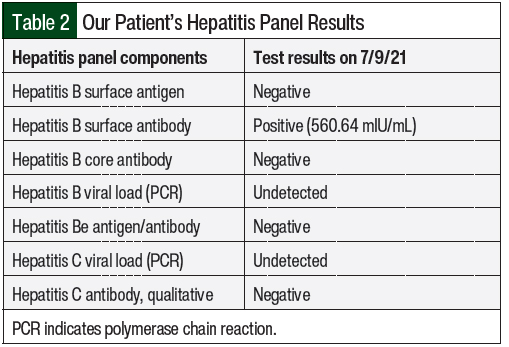

The patient completed 3 cycles of palbociclib therapy and had markedly elevated LFTs on her day-1 laboratory results before starting treatment cycle 4 (Table 1 and Figure). On July 9, 2021, her AST was 359 U/L (grade 3) and her ALT was 772 U/L (grade 4; Table 1). A hepatitis panel was negative (Table 2), and a CT scan showed no hepatic metastases or biliary dilation.

Other markers of liver impairment, including total bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase, were within normal limits. To ensure the resolution of the elevated LFTs, all potentially causative agents in the patient’s treatment were initially stopped. Thus, the patient was instructed to hold treatment with anastrozole and palbociclib and to permanently discontinue the turkey tail mushroom supplement. The patient was also instructed to avoid consuming alcohol and taking acetaminophen.

After a 2-week hold, on July 23, 2021, the patient’s AST and ALT began to downtrend to 156 U/L and 411 U/L, respectively. Treatment with anastrozole was restarted without issue at this time, and treatment with palbociclib 125 mg was resumed 3 weeks later on August 13, 2021, with weekly monitoring via laboratory testing. On August 26, 2021, the patient once again had grade 3/4 transaminases with normal total bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase.

Because the patient had previously received anastrozole and the turkey tail mushroom supplement concomitantly, which could have also caused or amplified the LFT elevations in addition to palbociclib, the patient’s reaction was analyzed using the Naranjo Adverse Drug Reaction Probability Scale.10 In practice, the Naranjo scale is an algorithm used to assess adverse drug events and whether there is a causal relationship between a drug and an untoward clinical event.10

Comprising 10 questions, the Naranjo scale assigns point values (–1, 0, +1, or +2) to answers of yes, no, or unknown.10 The scores are totaled and the results are classified as “definite” (score ≥9), “probable” (score of 5-8), “possible” (score of 1-4), or “doubtful” (score ≤0).11 Palbociclib was noted to be the probable cause of the patient’s elevated LFTs, whereas the anastrozole and turkey tail mushroom supplement were deemed possible causes.

Treatment with palbociclib was again held until the patient’s AST and ALT levels normalized, and 3 weeks later, on September 17, 2021, the patient restarted therapy with palbociclib at a reduced dose of 100 mg for 21 days (followed by 7 days off), which was repeated every 28 days. One week after the initiation of treatment with dose-reduced palbociclib 100 mg, the patient had recurrent grade 3 increased AST and ALT levels, and treatment with palbociclib was held once more. Approximately 1 week later, on October 1, 2021, treatment with palbociclib was again restarted at a final decreased dose of 75 mg for 21 days (with 7 days off), which was repeated every 28 days. At this dose, the patient’s LFTs remained at baseline without significant elevation, and she has continued to tolerate therapy.

Discussion

In our patient, we were able to deduce that treatment with palbociclib resulted in clear, asymptomatic hepatotoxicity, with AST and ALT elevations of more than 20 times the upper limit of normal.

Overall, palbociclib is considered a well-tolerated treatment, with the most commonly reported adverse events being hematologic toxicities.1 In comparison, the incidences of ribociclib- and abemaciclib-induced hepatotoxicities have been well-documented in original clinical trials and in postmarketing studies.11-17 Grade 3 or 4 increased AST and ALT were reported in 5.7% and 9.3%, respectively, of patients in the MONALEESA-2 trial; in 6% and 8.5%, respectively, of patients in MONALEESA-3; and in 4% and 5%, respectively, of patients in the MONALEESA-7 trial.11-13

Similarly, combined grade 3 and 4 ALT elevations were reported in 3.8% of patients in the MONARCH-1 trial and in 6.1% of patients in MONARCH-3, and combined grade 3 and 4 AST and ALT elevations were reported in 2.3% and 4.1%, respectively, of patients in MONARCH-2 and in 1.6% and 2.3%, respectively, of patients in the MONARCH-E trial.14-17

Given the higher incidence of grade 3 or 4 AST and ALT elevations, dosing recommendations that are specifically for hepatotoxicity during treatment are provided in the prescribing information for ribociclib and for abemaciclib.18,19

Reports of hepatotoxicity with palbociclib are rare and have primarily been anecdotal, stemming from cases with mostly asymptomatic presentation.20-22 In one study by Hyppolite and Hilzenrat, a patient with ER-positive metastatic breast cancer presented with asymptomatic AST up to 1052 U/L and ALT up to 1713 U/L, with normal total bilirubin 2 weeks after starting treatment with palbociclib and letrozole.20 On discontinuation of treatment with palbociclib and N-acetylcysteine, the patient’s LFTs returned to normal with no major liver damage.20

In another case, a woman with ER-positive, PR-positive, HER2-negative breast cancer had asymptomatic grade 3 or 4 AST and ALT elevations after receiving 3 cycles of treatment with palbociclib and fulvestrant.21 Subsequent dose reductions of palbociclib also resulted in elevated LFTs, and the patient eventually discontinued treatment.21

Last, Elder and colleagues presented the case of a woman with metastatic breast cancer who had asymptomatic AST and ALT elevations of 421 U/L and >700 U/L, respectively, after 3 treatment cycles of palbociclib and fulvestrant.22 Despite dose reductions of palbociclib, the patient continued to have elevated LFTs—although lower than she previously had—and treatment was permanently discontinued soon after.22

An interesting underlying parallel throughout all 3 cases was the delayed setting of the hepatotoxicity, which often happened after the patient received 3 cycles of treatment, which was similar to our patient. In addition, there is a probable dose-dependent correlation, with higher doses of palbociclib resulting in more severe toxicity.

To our knowledge, very few symptomatic patients have presented with palbociclib-induced hepatotoxicity. In our literature search, we identified 1 case, which was presented by Atallah and colleagues, of a patient with ER-positive, PR-positive, HER2-negative breast cancer who had grade 3 AST, ALT, and total bilirubin elevations after receiving 2 cycles of treatment with palbociclib, which led to jaundice and acute encephalopathy.23 This case ultimately resulted in fatal liver failure, with the proposed mechanism thought to be a drug interaction that resulted in the inhibition of palbociclib’s CYP3A4 hepatic metabolism.23

Concomitant drugs often make the diagnosis of drug-induced hepatotoxicity challenging. In our case, the patient was receiving anastrozole and a turkey tail mushroom supplement. Anastrozole is an aromatase inhibitor used in combination with palbociclib for the treatment of ER- or PR-positive locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer in postmenopausal women. Historically, anastrozole is considered safe to receive with palbociclib and has a relatively low risk for hepatotoxicity, with a reported incidence of 2% to 5% for mildly elevated LFTs.24

In the case report of a 70-year-old woman with ER-positive, PR-negative breast cancer who was receiving 1 mg daily of anastrozole and had elevated LFTs after 4 months of monotherapy, her AST rose as high as 640 U/L and her ALT was 1344 U/L.25 The patient discontinued treatment with anastrozole and her LFTs improved.25

For our patient, the reinitiation of treatment with anastrozole did not result in subsequent LFT elevations, and thus we were able to rule it out as a causative agent.

Our patient was also routinely taking a turkey tail mushroom supplement (Trametes versicolor or Coriolus versicolor), which is marketed for its potential immunomodulatory qualities. The main proteoglycan constituents of turkey tail mushroom, known as polysaccharide peptide (PSP) and polysaccharide Krestin, have been studied as adjunctive cancer treatments in Japan and China; however, turkey tail mushroom has not been extensively studied in the United States, and its efficacy and safety remain in question.26

There is not much data, if any, specifically on turkey tail mushroom’s interaction with palbociclib or on its tendency to cause hepatotoxicity by itself. One in vitro study of human liver microsomes demonstrated that PSP can act as a moderate competitive inhibitor of CYP3A4, but that it has a low potential to cause significant herb–drug interactions27; further pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic studies would be required to determine whether PSP can safely be administered with other drugs in vivo.

Palbociclib also shares the same metabolic pathway of CYP3A4, thus if taken concomitantly, turkey tail mushroom could theoretically increase the serum concentration of palbociclib in the body and potentiate adverse events. In addition, elevated liver enzymes and liver function impairment have been sporadically reported in the past when turkey tail mushroom is taken concomitantly with chemotherapy.28,29

In a meta-analysis assessing the efficacy and safety of turkey tail mushroom in patients with cancer, those receiving the supplement with conventional therapy had a higher incidence of increased LFTs compared with conventional therapy alone.28,29 This was particularly evident in patients with breast cancer, with a combined reported incidence of 38 cases of elevated AST and ALT compared with 22 cases in patients receiving chemotherapy only.29 However, statistical significance was not reported, and it is unclear if this increased incidence was a result of the combination of the turkey tail mushroom and chemotherapy or the turkey tail mushroom alone.28,29

In our patient, we initially suspected that turkey tail mushroom may have contributed to the increase in LFTs, and we theorized that it may have potentiated palbociclib’s effect on the liver. However, when the patient had subsequent LFT elevations after resuming treatment with palbociclib without the resumption of turkey tail mushroom, this theory became less likely.

One possibility that we did not explore because our patient tolerated dose-reduced palbociclib was a drug rechallenge with a different CDK 4/6 inhibitor. Three previous case reports have documented the safety of rechallenging with palbociclib or abemaciclib after ribociclib-induced hepatotoxicity,30-32 but, to our knowledge, no cases have been published on the success of abemaciclib or ribociclib rechallenge after palbociclib-induced hepatotoxicity.

Future investigators may consider this as an alternative option; however, it is important to note that the incidence of hepatotoxicity is often higher with abemaciclib and ribociclib treatment than with palbociclib, and careful consideration should be taken if switching to a different CDK 4/6 inhibitor.30-32

Conclusion

This case report highlights that palbociclib can cause uncommon but asymptomatically severe AST and ALT elevations in patients without baseline liver dysfunction and exemplifies the need for close monitoring of LFTs in patients who are receiving palbociclib, especially beyond the first few treatment cycles.

Healthcare providers should be aware of this adverse event and attention should also be paid to potential drug–drug interactions, particularly involving CYP3A4. In addition, in patients with palbociclib-induced hepatotoxicity, the management of nonhematologic toxicities according to the prescribing information for palbociclib can be an effective treatment strategy given the apparent dose-dependent levels of AST and ALT elevations.

Future investigation should further explore severe AST and ALT elevations to understand the circumstances that result in hepatotoxicity after receiving treatment with palbociclib.

Author Disclosure Statement

Dr Hutchinson is an Advisory Board Consultant to Novartis; Dr Green, Dr Jacques, Dr Kim, Dr Shin, Ms Haggett, and Ms Straw have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- Ibrance (palbociclib) capsules, for oral use [prescribing information]. Pfizer; December 2022. https://labeling.pfizer.com/ShowLabeling.aspx?id=2191. Accessed March 7, 2023.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines): Breast Cancer. Version 3.2023. March 3, 2023. www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/breast.pdf. Accessed March 10, 2023.

- Finn RS, Crown JP, Lang I, et al. The cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitor palbociclib in combination with letrozole versus letrozole alone as first-line treatment of oestrogen receptor-positive, HER2-negative, advanced breast cancer (PALOMA-1/TRIO-18): a randomised phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:25-35.

- Turner NC, Ro J, André F, et al. Palbociclib in hormone-receptor–positive advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:209-219.

- Pfizer. Study of letrozole with or without palbociclib (PD-0332991) for the first-line treatment of hormone-receptor positive advanced breast cancer. ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT00721409. Updated November 4, 2019. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/results/NCT00721409?view=results. Accessed March 15, 2023.

- Finn RS, Martin M, Rugo HS, et al. Palbociclib and letrozole in advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1925-1936.

- Cristofanilli M, Turner NC, Bondarenko I, et al. Fulvestrant plus palbociclib versus fulvestrant plus placebo for treatment of hormone-receptor-positive, HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer that progressed on previous endocrine therapy (PALOMA-3): final analysis of the multicentre, double-blind, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:425-439. Errata in: Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:e136; Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:e270.

- Diéras V, Rugo HS, Schnell P, et al. Long-term pooled safety analysis of palbociclib in combination with endocrine therapy for HR+/HER2- advanced breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019;111:419-430.

- Giordano C, Rivas J, Zervos X. An update on treatment of drug-induced liver injury. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2014;2:74-79.

- Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1981;30:239-245.

- Hortobagyi GN, Stemmer SM, Burris HA, et al. Ribociclib as first-line therapy for HR-positive, advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1738-1748. Erratum in: N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2582.

- Slamon DJ, Neven P, Chia S, et al. Phase III randomized study of ribociclib and fulvestrant in hormone receptor–positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2–negative advanced breast cancer: MONALEESA-3. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:2465-2472.

- Tripathy D, Im SA, Colleoni M, et al. Ribociclib plus endocrine therapy for premenopausal women with hormone-receptor-positive, advanced breast cancer (MONALEESA-7): a randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:904-915.

- Dickler MN, Tolaney SM, Rugo HS, et al. MONARCH 1, a phase II study of abemaciclib, a CDK4 and CDK6 inhibitor, as a single agent, in patients with refractory HR+/HER2– metastatic breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:5218-5224. Erratum in: Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24:5485.

- Sledge GW Jr, Toi M, Neven P, et al. MONARCH 2: abemaciclib in combination with fulvestrant in women with HR+/HER2– advanced breast cancer who had progressed while receiving endocrine therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:2875-2884.

- Goetz MP, Toi M, Campone M, et al. MONARCH 3: abemaciclib as initial therapy for advanced breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:3638-3646.

- Johnston SRD, Harbeck N, Hegg R, et al; for the monarchE committee members and investigators. Abemaciclib combined with endocrine therapy for the adjuvant treatment of HR+, HER2–, node-positive, high-risk, early breast cancer (monarchE). J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:3987-3998.

- Verzenio (abemaciclib) tablets, for oral use [prescribing information]. Eli Lilly and Company; March 2023. https://pi.lilly.com/us/verzenio-uspi.pdf?s=pi. Accessed March 9, 2023.

- Kisqali (ribociclib) tablets, for oral use [prescribing information]. Novartis; October 2022. www.novartis.us/sites/www.novartis.us/files/kisqali.pdf. Accessed March 9, 2023.

- Hyppolite JJ, Hilzenrat N. Palbociclib-induced severe hepatitis: a case study and literature review. Can Liver J. 2021;4:433-437.

- Roberts BA, Ibrahim M, Stone E. Elevated liver function tests in a patient on palbociclib and fulvestrant. J Community Support Oncol. 2018;16:e277-e279.

- Elder C, Ohana Z, Younas W. Fulvestrant- and palbociclib-induced hepatotoxicity in a patient with breast cancer: a case report. J Hematol Oncol Pharm. 2020;10(4):235-240.

- Atallah R, Parker NA, Hamouche K, et al. Palbociclib-induced liver failure. Kans J Med. 2020;13:81-83.

- Arimidex (anastrozole) tablets for oral use [prescribing information]. ANI Pharmaceuticals; August 2019. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/fda/fdaDrugXsl.cfm?setid=acbfaaa9-503c-4691-9828-76a7146ed6de&type=display. Accessed March 9, 2023.

- Inno A, Basso M, Vecchio FM, et al. Anastrozole-related acute hepatitis with autoimmune features: a case report. BMC Gastroenterol. 2011;11:32. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-11-32.

- Standish LJ, Wenner CA, Sweet ES, et al. Trametes versicolor mushroom immune therapy in breast cancer. J Soc Integr Oncol. 2008;6:122-128.

- Yeung JHK, Or PMY. Polysaccharide peptides from Coriolus versicolor competitively inhibit model cytochrome P450 enzyme probe substrates metabolism in human liver microsomes. Phytomedicine. 2012;19:457-463.

- Therapeutic Research Center. Turkey tail mushroom. Natural Medicines database. Updated August 16, 2022. https://naturalmedicines.therapeuticresearch.com/databases/food,-herbs-supplements/professional.aspx?productid=648. Accessed January 11, 2023.

- Eliza WLY, Fai CK, Chung LP. Efficacy of Yun Zhi (Coriolus versicolor) on survival in cancer patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. Recent Pat Inflamm Allergy Drug Discov. 2012;6:78-87.

- Fuentes-Antrás J, de Luna A, López de Sá A, et al. Safety and efficacy of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor rechallenge following ribociclib-induced limiting hypertransaminasemia. Breast. 2020;54:160-163.

- Meynard L, Grellety T. CDK 4/6 inhibitor successful rechallenge after limiting hepatic toxicity. Breast J. 2020;26:255-257.

- Farhat F, Tarabaih M, Kanj A, et al. Palbociclib safety and efficacy beyond ribociclib-induced liver toxicity in metastatic hormone-receptors positive breast cancer patient. Anticancer Drugs. 2020;31:85-89.