Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) is a myeloproliferative neoplasm that accounts for approximately 15% of all adults diagnosed with leukemia.1 CML is characterized by the presence of the Philadelphia chromosome, a translocation between chromosomes 9 and 22 [t(9;22)], resulting in the BCR-ABL1 fusion gene.2 The treatment for patients with CML includes long-term tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) therapy with the first-generation TKI imatinib or with the second-generation TKIs—dasatinib, nilotinib, or bosutinib. The choice of therapy is often established after consideration of the side-effect profile of each TKI, the patient’s age and comorbid conditions, potential drug interactions, and the patient’s CML risk score.2

The TKIs are generally well-tolerated, with common adverse events reported including gastrointestinal side effects, edema, musculoskeletal pain, and rash.3,4 An uncommon adverse event of treatment with imatinib or dasatinib is gynecomastia.5-10

To date, several reports have been published related to imatinib-induced gynecomastia,5-9 and only 1 report of this adverse event arising during therapy with dasatinib.10

Currently, no recommendations are given in the dasatinib’s prescribing information for the monitoring and management of gynecomastia.4 We present 2 cases of dasatinib-induced gynecomastia and a review of the literature to examine this adverse event.

Case 1

A 58-year-old man with unremarkable medical and medication histories presented to his primary care physician with bilateral edema and incidentally had an increased white blood cell (WBC) count and splenomegaly. He was subsequently admitted to the hospital with a WBC count of 353 × 103/mm3.

Shortly after admission, the patient was diagnosed with CML, based on a marrow biopsy and being Philadelphia chromosome–positive (p210), and he was initiated treatment with dasatinib 100 mg orally, daily. The patient’s Sokal score was calculated as 2.3 points, which placed him as having high-risk CML.2

The patient received hydroxyurea 2000 mg twice daily for 2 days for cytoreduction, before starting treatment with dasatinib, as well as hydroxyurea 3000 mg twice daily for 4 more days while receiving dasatinib.

The patient continued to take dasatinib for 3 more weeks before he was diagnosed with cytopenias, including a WBC count of 2.84 × 103/mm3, an absolute neutrophil count of 0.07 K/uL, hemoglobin of 9.6 g/dL, and a platelet count of 89 × 109/L. When the cytopenias resolved, treatment with dasatinib was resumed, at 80 mg daily, after being held for 17 days.

Approximately 2 months after starting dasatinib treatment, the patient presented to his primary care physician with painful breast, which he originally described as chest pain, as well as breast enlargement, which was consistent with gynecomastia. The results of a comprehensive metabolic panel were within normal limits.

The laboratory workups (at different times) included an estradiol level of 36 pg/mL (reference range, 26-61 pg/mL), follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) of 4.3 IU/L (reference range, 1-12 IU/L), prolactin of 12.8 ng/mL (reference range, 0-14.2 ng/mL), testosterone (percent free) of 1.51% (reference range, 1.22%-2.81%), testosterone (free) of 7.91 ng/dL (reference range, 6.16-19.4 ng/dL), and a total testosterone of 525 ng/dL (reference range, 249-836 ng/dL).

One month after the symptom presentation, the patient had a mammogram (for breast enlargement), which showed findings consistent with gynecomastia. The patient was offered the option of switching from dasatinib to an alternative TKI to avoid this adverse event, but he chose to continue to use dasatinib, because he was having response to therapy. Nine months after the patient was diagnosed with dasatinib-induced gynecomastia, he was still using dasatinib, and the symptoms of gynecomastia were not getting worse.

Case 2

A 40-year-old man with no significant medical history was diagnosed with CML and was initiated treatment with oral dasatinib 100 mg, daily. After 1 month of treatment, the patient was diagnosed with cytopenias, which required the cessation of the dasatinib treatment. The laboratory values were not available when writing up this case because of a change in the institution’s electronic medical record. Reporting relied heavily on progress note documentation. When the patient’s blood counts recovered, treatment with dasatinib was resumed at 80 mg daily; this therapy was continued for 4 years without issue.

Approximately 4 years after starting dasatinib therapy, the patient had new-onset breast tenderness, which he described as chest pain. An ultrasound and a mammogram revealed findings that were consistent with gynecomastia.

The laboratory workups (at different times) showed the patient had a testosterone level of 616 ng/dL (reference range, 6.16-19.4 ng/dL), prolactin of 8 ng/mL (reference range, 0-14.2 ng/mL), thyroid-stimulating hormone of 1.32 uIU/mL (reference range, 0.4-5 uIU/mL), and free T4 of 1.16 ng/dL (reference range, 0.89-1.76 ng/dL).

The patient was not receiving any concomitant medications in addition to dasatinib, and he had no history of alcohol use. No other obvious or potential causes of gynecomastia were identified. The patient continued to take dasatinib, without any worsening of or improvement in gynecomastia.

Discussion

We describe dasatinib-induced gynecomastia in 2 patients, both of whom received reduced dose of dasatinib. The onset of gynecomastia was different in each of the 2 patients in terms of the duration of dasatinib therapy. Although the adverse event of gynecomastia would score as a 6 (ie, probable adverse drug reaction) on the Naranjo scale, neither patient had other identifiable causes for gynecomastia.11

The limitations to the application of the Naranjo scale to our 2 patients are that dasatinib was never stopped and then readministered, the dose of the drug was not increased, and dasatinib was not measured in the body fluid of either patient.11

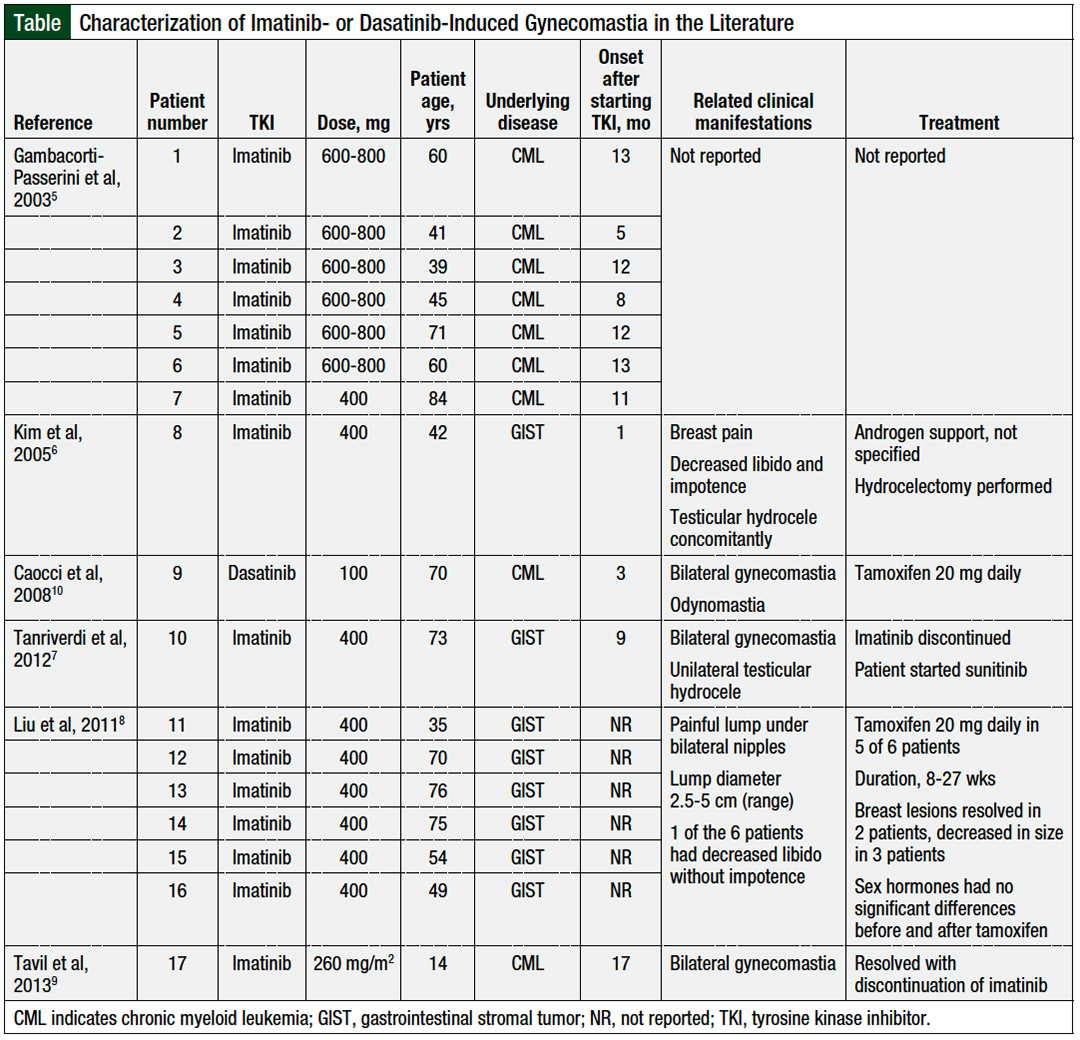

As noted earlier, to our knowledge, only 1 other case report of dasatinib-induced gynecomastia has been published,10 but several reports of imatinib-induced gynecomastia have been published (Table).5-10

Gynecomastia is defined as the expansion of the glandular epithelial tissue in breasts in men.12 The incidence of gynecomastia can vary, depending on the man’s age, and the reported incidence ranges from 32% to 65%.12

The causes of gynecomastia range from organ dysfunction (ie, hypogonadism, hyperthyroidism, or liver or renal disease), types of cancer, and the use of certain medications.12 Through different mechanisms, these causes can lead to an imbalance between free estrogen and free androgen in breast tissue.12,13

The receptors for estrogen and androgen are found in breast tissue, where estrogen stimulates proliferation and androgen inhibits the growth of the mammary gland. Excess estrogen or decreased androgen can tip the balance of these hormones, causing an abnormal hormonal ratio, which can modify the hormonal signaling, thereby leading to gynecomastia.12,13

The postulated mechanisms of action for dasatinib- and imatinib-induced gynecomastia include the inhibition of platelet-derived growth factor (PDGFR) and/or c-KIT.3,4 The testes express c-KIT and PDGFR, which contribute to testosterone production and secretion.14,15 PDGFR activation is essential for testes organogenesis and Leydig-cell differentiation, whereas PDGFR-A–specific subtype is required for Leydig-cell recruitment and spermatogenesis. The increase in progesterone and 17-hydroxyprogesterone in most patients with gynecomastia could be caused by a decreased testosterone production, with a resultant rise in testosterone precursors.14,15

Although imatinib-induced gynecomastia5-9 has been reported more often than gynecomastia associated with dasatinib treatment,10 dasatinib is a more potent inhibitor of c-KIT and of PDGFR than imatinib.16

Gynecomastia is diagnosed through a clinical evaluation. Differentiating between gynecomastia, pseudogynecomastia, and breast carcinoma can be established by a physical examination.12,13 A mammograph can be performed with at least 90% sensitivity and specificity to differentiate between gynecomastia and breast carcinoma.17

To aid in identifying the cause of gynecomastia, hormone levels may aid in the diagnosis, including human chorionic gonadotropin, luteinizing hormone, testosterone, and estradiol.12,13 Testosterone and luteinizing-hormone levels should be measured in the morning, to align with their circadian rhythm secretion.12

If the testosterone level is low, free testosterone may be measured to evaluate for hypogonadism. Increased luteinizing hormone with decreased testosterone is characteristic of primary hypogonadism, whereas normal or decreased luteinizing-hormone levels and decreased testosterone can be characteristic of secondary hypogonadism.12

Although these hormones may be helpful in identifying the cause of gynecomastia, as in the case of our 2 patients, most patients with gynecomastia do not present with hormonal abnormalities.12,13 Thyroid studies may also be beneficial at baseline and during TKI treatment, because dasatinib has been linked to hyperthyroidism, which can affect testosterone levels.18

Imatinib-induced gynecomastia has been well-described in the literature in patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumor and in patients with CML, with an onset ranging from as early as 1 month to 17 months.5-9 In contrast, in the only 1 previous case report of dasatinib-induced gynecomastia, this side effect occurred after 2 months of therapy.10

Among our 2 cases, the first patient had a similar onset, at 2 months, but our second patient had a much longer time to onset, at approximately 4 years. As men age, the average decline in serum testosterone is 1% to 2% annually19,20; however, because the 2 patients were relatively young, it is unlikely that the decrease in testosterone was caused by aging.

The largest retrospective study to date examining imatinib-induced gynecomastia, by Gambacorti-Passerini and colleagues, showed that 7 (18%) of 38 men who received imatinib had gynecomastia, and by 5 to 16 months, 35 (92%) of 38 men had abnormally low levels of serum testosterone.5 Specifically, the diagnosis of gynecomastia in that study was associated with hormonal abnormalities, and with the use of high doses (>600-800 mg) of imatinib. Patients who did not have gynecomastia still had a mean reduction in free testosterone levels of 6.36 pmol/L during treatment with imatinib.5

Some reports have demonstrated the presence of gynecomastia when testosterone levels decreased below the normal range, whereas others showed this link when testosterone levels decreased but remained within the normal limits.6-10

In a study by Ghalaut and colleagues of 34 men who were receiving imatinib, the proportion of patients with low testosterone increased from 11.8% at baseline to 58.8% at 6 months, but these men did not have gynecomastia.21 Additional hormone changes included increased luteinizing hormones and FSH levels, in line with increased FSH and luteinizing-hormone secretion, as feedback inhibition to promote testosterone production.21

No such studies have been conducted with other second-generation TKIs in the treatment of CML. In our 2 patient cases, because gynecomastia with dasatinib treatment has only been reported in 1 article, we did not measure the baseline laboratory hormone levels. A comparison could not be made between the baseline value and the value after starting treatment with dasatinib.

There is currently no standard treatment for TKI-induced gynecomastia, likely because it is a rare event. The reported therapeutic approaches include androgen support, tamoxifen, and switching to a different TKI.9,10,21

Tamoxifen is a selective estrogen receptor modulator that leads to decreased estrogen effects.22 Serious consideration should be used while weighing the risks versus the benefits of adding tamoxifen to remain on the current TKI versus switching to a different TKI. To date, tamoxifen has only been used in a total of 7 patients in the literature for this indication, and is associated with serious adverse events, including cardiovascular events.21,22 Considerations for treatment with tamoxifen include pertinent drug–drug interactions and serious warnings, including hepatotoxicity, thromboembolic events, and bone marrow suppression.22

The common drug class of selective serotonin inhibitors also interacts with tamoxifen, and may render tamoxifen inactive.22 Careful review of the current medication interactions is critical before starting treatment with tamoxifen.22 Androgen support options can be found in the Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline for testosterone therapy in men with androgen deficiency syndromes.19

Along with gynecomastia, other symptoms related to decreased testosterone have been described in patients with dasatinib- or imatinib-induced gynecomastia, including decreased libido, impotence, and hydrocele.6,8-10 Decreased testosterone levels have been associated with decreased bone mineral density, loss of muscle mass, and increase in metabolic syndrome.19,23-26 The physical symptoms of decreased testosterone can include hot flashes, depression, and decreased libido,19 which can significantly affect a patient’s quality of life.

In our 2 cases, both patients decided to continue treatment with dasatinib and careful monitoring, which consisted of a physical examination during follow-up, and encouraging both patients to report an increase in breast tissue or painful symptoms. Once gynecomastia was identified, neither patient wanted to discontinue therapy or switch to an alternative agent.

Because of the mechanism of this adverse event, it is unlikely that pausing therapy and resuming treatment after the symptoms have resolved would have led to the resolution of gynecomastia while receiving TKI therapy.

Conclusion

To our knowledge, this is only the second report of dasatinib-induced gynecomastia (in 2 patients). By contrast, imatinib-induced gynecomastia has been well-described in several reports and may share a similar mechanism of action with dasatinib-induced gynecomastia. Although gynecomastia is rare, based on the prevalence of low-testosterone levels while receiving imatinib, it may be appropriate to monitor the testosterone level at baseline before initiating imatinib or dasatinib therapy, and again if the patient reports symptoms of low testosterone.

Additional studies should be conducted to determine the appropriate monitoring of testosterone levels in patients receiving TKI therapy. Patients should be educated on gynecomastia as a potential adverse event with TKI treatment and on the need to report any symptoms that may be characteristic of low-testosterone syndromes.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients’ willingness to share their cases.

Author Disclosure Statement

Dr Signorelli is a consultant to Bristol Myers Squibb and has received honoraria from AbbVie. Dr Fathi has been a consultant to Pfizer, Trillium, AbbVie, Kura, Blueprint, Genentech, Agios/Servier, Bristol Myers Squibb, Morphosys, Kite, Foghorn, and Takeda, and has received clinical trial support from Agios/Servier, Bristol Myers Squibb, and AbbVie. Dr Hobbs is on the Advisory Board of Pfizer, Novartis, Bristol Myers Squibb/Celgene, Constellation, Incyte, and AbbVie, and has received research support from Incyte and Constellation.

References

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70:7-30.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines): Chronic Myeloid Leukemia. Version 2.2022. November 15, 2021. www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/cml.pdf. Accessed January 26, 2022.

- Gleevec (imatinib mesylate) tablets, for oral use [prescribing information]. Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; August 2020. www.novartis.us/sites/www.novartis.us/files/gleevec_tabs.pdf. Accessed January 28, 2022.

- Sprycel (dasatinib) tablets, for oral use [prescribing information]. Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; June 2021. https://packageinserts.bms.com/pi/pi_sprycel.pdf. Accessed January 28, 2022.

- Gambacorti-Passerini C, Tornaghi L, Cavagnini F, et al. Gynaecomastia in men with chronic myeloid leukaemia after imatinib. Lancet. 2003;361:1954-1956.

- Kim H, Chang HM, Ryu MH, et al. Concurrent male gynecomastia and testicular hydrocele after imatinib mesylate treatment of a gastrointestinal stromal tumor. J Korean Med Sci. 2005;20:512-515.

- Tanriverdi O, Unubol M, Taskin F, et al. Imatinib-associated bilateral gynecomastia and unilateral testicular hydrocele in male patient with metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumor: a literature review. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2012;18:303-310.

- Liu H, Liao G, Yan Z. Gynecomastia during imatinib mesylate treatment for gastrointestinal stromal tumor: a rare adverse event. BMC Gastroenterol. 2011;11:116. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-11-116.

- Tavil B, Kınık S, Gözen A, Olcay L. Gynecomastia in a boy with chronic myeloid leukemia during imatinib therapy. Turk J Hematol. 2013;30:336-337.

- Caocci G, Atzeni S, Orrù N, et al. Gynecomastia in a male after dasatinib treatment for chronic myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2008;22:2127-2128.

- Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1981;30:239-245.

- Braunstein GD. Gynecomastia. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1229-1237.

- Kanakis GA, Nordkap L, Bang AK, et al. EAA clinical practice guidelines—gynecomastia evaluation and management. Andrology. 2019;7:778-793. Epub 2019 May 16.

- Basciani S, Mariani S, Spera G, Gnessi L. Role of platelet-derived growth factors in the testis. Endocr Rev. 2010;31:916-939.

- Sette C, Dolci S, Geremia R, Rossi P. The role of stem cell factor and of alternative c-kit gene products in the establishment, maintenance and function of germ cells. Int J Dev Biol. 2000;44:599-608.

- Chen Z, Lee FY, Bhalla KN, Wu J. Potent inhibition of platelet-derived growth factor-induced responses in vascular smooth muscle cells by BMS-354825 (dasatinib). Mol Pharmacol. 2006;69:1527-1533.

- Evans GFF, Anthony T, Appelbaum AH, et al. The diagnostic accuracy of mammography in the evaluation of male breast disease. Am J Surg. 2001;181:96-100. Erratum in: Am J Surg. 2001;181:579.

- Kim TD, Schwarz M, Nogai H, et al. Thyroid dysfunction caused by second-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors in Philadelphia chromosome-positive chronic myeloid leukemia. Thyroid. 2010;20:1209-1214.

- Bhasin S, Cunningham GR, Hayes FJ, et al. Testosterone therapy in men with androgen deficiency syndromes: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:2536-2559. Errata in: J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:4101; J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;106:e2848.

- Feldman HA, Longcope C, Derby CA, et al. Age trends in the level of serum testosterone and other hormones in middle-aged men: longitudinal results from the Massachusetts Male Aging Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:589-598.

- Ghalaut VS, Prakash G, Bansal P, et al. Effect of imatinib on male reproductive hormones in BCR-ABL positive CML patients: a preliminary report. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2014;20:243-248.

- Soltamox (tamoxifen citrate) oral solution [prescribing information]. Fortovia Therapeutics; June 2019. https://soltamox.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/soltamox-pi.pdf. Accessed January 30, 2022.

- Wang C, Cunningham G, Dobs A, et al. Long-term testosterone gel (AndroGel) treatment maintains beneficial effects on sexual function and mood, lean and fat mass, and bone mineral density in hypogonadal men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:2085-2098.

- Grinspoon S, Corcoran C, Lee K, et al. Loss of lean body and muscle mass correlates with androgen levels in hypogonadal men with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome and wasting. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81:4051-4058.

- Basaria S. Androgen deprivation therapy, insulin resistance, and cardiovascular mortality: an inconvenient truth. J Androl. 2008;29:534-539.

- Laughlin GA, Barrett-Connor E, Bergstrom J. Low serum testosterone and mortality in older men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:68-75.