The incidence of atrial fibrillation after hematopoietic stem-cell transplant (HSCT) is between 7% and 27% after HSCT.1-4 Patients who received an allogeneic HSCT and those who received the drug melphalan also have shown an increased risk for atrial fibrillation.1,4,5 The onset of atrial fibrillation after HSCT has been associated with increased rates of intensive care unit (ICU) admissions and longer hospital stays among this patient population.1-4

Previous studies have identified potential risk factors for atrial fibrillation in the setting of HSCT. Cardiac risk factors, such as a history of cardiac arrhythmias, baseline cardiac dysfunction, and previous exposure to anthracyclines, have been identified in multiple studies.1,2,4-8 Other potential risk factors identified across multiple studies include increased age at the time of HSCT and elevated baseline serum creatinine.1-5,7,8

Although previous studies have evaluated isolated potassium and magnesium levels in patients who had newly developed atrial fibrillation post-HSCT, the lack of substantiated data has limited the consideration of electrolyte abnormalities as an established risk factor for atrial fibrillation in the HSCT setting.1,8 Nevertheless, low levels of serum potassium and magnesium have been identified as potential risk factors for atrial fibrillation in the general population.9-11

A recent meta-analysis showed that patients with low serum potassium level had a 1.6-fold increased risk for supraventricular arrhythmias, defined as atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter, with increasing age being a significant risk factor.11 Extrapolation of this information to patients undergoing HSCT indicates a high risk for electrolyte abnormalities and potentially for atrial fibrillation, with the highest risk approximately 8 to 10 days after HSCT, a time range that has previously been identified as the electrolyte nadir after HSCT.12

Regardless of the role that electrolyte abnormalities play in the onset of atrial fibrillation after HSCT, uncertainty remains as to whether the incidence of atrial fibrillation is transient or persistent in nature. Previous studies have shown that 25% to 76% of patients had a recurrence of atrial fibrillation after HSCT up to 30 days later.2,5,6 No long-term follow-up data regarding atrial fibrillation management for patients who have undergone autologous HSCT are available. Therefore, it remains unclear whether such patients require lifelong treatment and monitoring.

The purpose of this current study was to review retrospectively whether an associated risk exists between having electrolyte abnormalities around the time of autologous HSCT and the onset of atrial fibrillation. In addition, we evaluated the rate of recurrence and the treatment method of atrial fibrillation in patients who had atrial fibrillation 1 year after HSCT.

Methods

This single-center, retrospective cohort study included patients who underwent autologous HSCT at Avera McKennan Hospital & University Health Center in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, between November 2007 and November 2018. Patients were included if they had an autologous HSCT at the facility within this study period. Patients were excluded from the study if they had documented atrial fibrillation on baseline electrocardiogram (EKG) results.

Patients were included in the atrial fibrillation cohort if they had an EKG showing the presence of atrial fibrillation during their hospital stay after undergoing HSCT. The patients who did not have atrial fibrillation after HSCT constituted the control group. We compared the outcomes among these 2 cohorts.

We identified patients through the institution’s electronic health record systems. This study was approved by the institution’s investigational review board before study initiation.

The patients’ baseline demographic and clinical data were obtained from the electronic medical record. Baseline demographic data included age, sex, race, type of malignancy, serum creatinine level, thyroid-stimulating hormone level, number of previous treatments, history of chronic kidney disease, ibritumomab tiuxetan administration, and mediastinal radiation. Other data points collected related to hospital stay included the onset of sepsis, ICU admission, hospital length of stay, onset of mucositis, and onset of Clostridium difficile infection.

Serum electrolytes, including potassium and magnesium levels, were collected at baseline and then daily through neutrophil engraftment. If multiple electrolyte levels were drawn in one day, the first level of the day was used for data collection, because repeated laboratory blood tests might have been completed to assess the efficacy of electrolyte replacement. We also collected EKG results at baseline before HSCT and any subsequent EKGs until 1 year after HSCT.

For patients who had atrial fibrillation, we collected data about their cardiac history; calculated congestive heart failure, hypertension, age (65-74 years; ≥75 years), diabetes mellitus, stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA), vascular disease, sex category (by CHA2DS2-VASc score for atrial fibrillation); and atrial fibrillation treatment modalities and duration for up to 1 year post-HSCT.

The primary study end point was the presence of atrial fibrillation after HSCT, specifically focusing on the impact of hypokalemia and hypomagnesemia on its onset. EKG results were used to identify atrial fibrillation in patients. Normal serum potassium level was defined as 3.5 mEq/L to 5.1 mEq/L, and normal serum magnesium level was defined as 1.6 mg/dL to 2.6 mg/dL, per laboratory reference range.

The secondary end points included the rate of ICU admission, hospital length of stay, sepsis onset, incidence of mucositis, and C difficile infection. We conducted a subgroup analysis of the patients with atrial fibrillation post-HSCT to examine the rate of recurrence and the method of treatment of atrial fibrillation at 1 year after HSCT.

Statistical Analysis

We used Fisher’s exact test to assess the relationship between categorical variables. A Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used for continuous variables, because of a non-normal distribution of data. In all statistical tests, an effect was considered statistically significant if the P value of its corresponding statistical test was <.05. All statistical computations were performed using R version 3.5.2 (R Foundation; Vienna, Austria).

Results

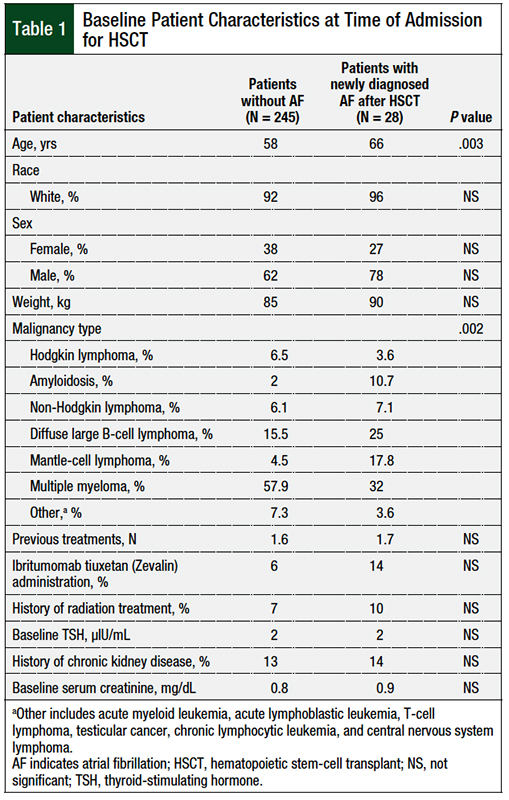

Between November 2007 and November 2018, a total of 275 patients had autologous HSCT at our facility; 2 patients were excluded, because they had atrial fibrillation at baseline. After HSCT, a total of 28 (10.2%) patients had newly diagnosed atrial fibrillation (ie, the atrial fibrillation group), and 245 patients were allocated to the control cohort (Table 1). The average time to the onset of atrial fibrillation was day 8 after HSCT, with a range of day 1 to day 17 after HSCT.

The patients’ baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1. A significant difference in age at the time of HSCT was found between the atrial fibrillation cohort and the control cohort (58 vs 66 years, respectively; P = .003). A significant difference between the cohorts also existed in the distribution of underlying malignancies. No significant differences were noted between the cohorts with regard to race, gender, body weight, number of previous treatments, previous radiation therapy, ibritumomab tiuxetan administration, thyroid function, and renal function (Table 1).

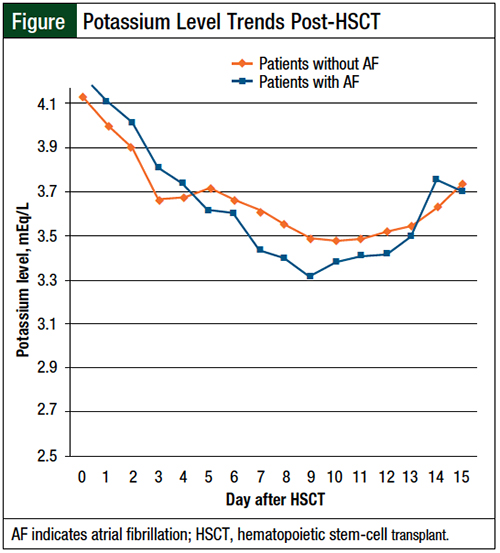

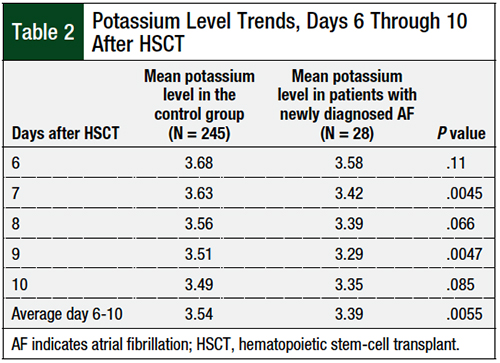

Serum potassium levels were lower during days 5 to 13 after HSCT in patients who had newly diagnosed atrial fibrillation, as illustrated in the Figure. The mean potassium levels on days 6 to 10 after HSCT were significantly lower in patients who had atrial fibrillation than in the control group (3.39 mEq/L vs 3.54 mEq/L, respectively; P = .0055; Table 2). No significant difference in serum magnesium levels was identified between the 2 cohorts.

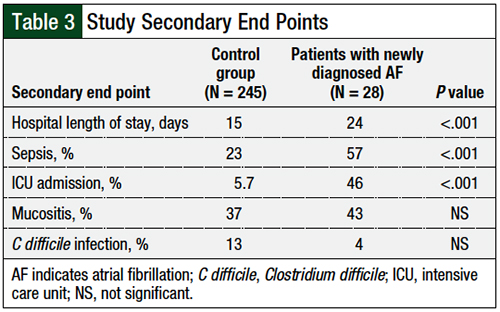

Regarding the secondary end points of the study, patients who had newly developed atrial fibrillation had a higher incidence of sepsis than the control group (57% vs 23%, respectively; P <.001) and ICU admission (46% vs 5.7%; P <.001). Similarly, these patients had a longer hospital stay than the control group (24 days vs 15 days, respectively; P <.001). No significant differences were identified between the cohorts regarding the incidence of mucositis or of C difficile infection (Table 3).

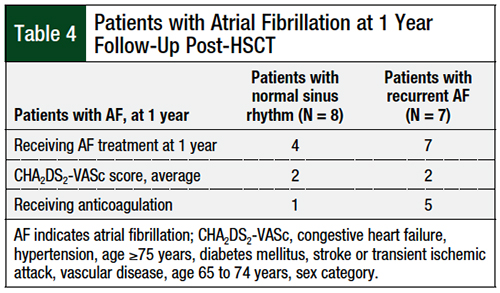

Among the subgroup of 28 patients who had atrial fibrillation after HSCT, 15 (53%) patients had 1-year follow-up data available for analysis. Of these 15 patients, 7 (46.6%) patients had EKG results subsequent to their initial HSCT admission that remained positive for atrial fibrillation, whereas the other 8 (53.3%) patients maintained normal sinus rhythm after resolution of their initial episode of atrial fibrillation.

The 7 patients whose subsequent EKGs showed atrial fibrillation were receiving treatment to control the rate or rhythm, whereas only 4 patients in the subgroup of patients who maintained normal sinus rhythm received treatment for atrial fibrillation. The average calculated HA2DS2-VASc score of the entire atrial fibrillation cohort was 2. Between the 2 cohorts, 6 patients were receiving therapeutic anticoagulation.

An interesting finding resulted from the secondary end point of 1-year follow-up data for patients with newly developed atrial fibrillation after HSCT. Up to this point, the follow-up for such patients had only been until 30 days after discharge from the original HSCT hospital admission. Of the 28 patients who had atrial fibrillation after HSCT, 15 (54%) had 1-year follow-up data available (Table 4).

All the patients who continued to have atrial fibrillation after HSCT were receiving treatment for atrial fibrillation, but only approximately 50% of the patients who remained in normal sinus rhythm were receiving treatment. Less than 50% of the patients were receiving oral anticoagulation, although the mean CHA2DS2-VASc score of the group was 2.

Discussion

Our results show that 7 of 15 (46.6%) patients either remained in persistent atrial fibrillation or had at least 1 recurrence episode during the follow-up period. This demonstrates that many patients continue to have problems with atrial fibrillation even after the initial 30 days after HSCT.

The findings of this study have encouraged our institution to complete a more thorough cardiovascular evaluation and outpatient monitoring for atrial fibrillation in this patient population. Many patients who undergo autologous HSCT have electrolyte abnormalities as a result. Previous studies have described factors that could contribute to the onset of atrial fibrillation, including increased age and elevated serum creatinine at baseline,1-8 but electrolyte abnormalities after HSCT had yet to be evaluated before this study.

Our results confirm that increased age is a potential risk factor for atrial fibrillation after HSCT; the mean age of the atrial fibrillation cohort was 66 years compared with 58 years in the cohort without atrial fibrillation (P = .003). Our results did not identify elevated serum creatinine level at baseline as a potential risk factor, with a 0.1-mg/dL difference in mean serum creatinine between the 2 study cohorts, which did not reach statistical significance.

Other cardiac risk factors identified in previous studies, such as a history of cardiac arrhythmias and baseline cardiac dysfunction, could not be evaluated in this study, because of inconsistent reporting within the electronic medical record.2-8 We also chose not to evaluate the receipt of melphalan as a potential risk factor, as was previously identified by Feliz and colleagues,1 because the number of patients who did not receive melphalan in their conditioning regimens was too small to be analyzed. In addition, we found a significant difference in the distribution of various malignancy types between the 2 cohorts. This was thought to be a result of the small sample size of the cohort to have any clinical significance.

In our study, we identified hypokalemia as potentially being associated with an increased risk for atrial fibrillation after HSCT. An identifiable trend in potassium level was seen from day 6 to day 10 after HSCT, when the atrial fibrillation cohort’s serum potassium levels decreased significantly below the other cohort’s levels, as seen in the Figure.

Also of note, the average time for patients to have newly developed atrial fibrillation after HSCT was 8 days, which falls within the window of when electrolytes were at their lowest. The average potassium levels significantly differed between the atrial fibrillation cohort and the control cohort from days 6 to 10 post-HSCT (3.39 mEq/L vs 3.54 mEq/L, respectively; P = .0055).

We could not reach conclusions regarding the impact of hypomagnesemia on the incidence of atrial fibrillation post-HSCT, because the reporting of magnesium levels at our facility was inconsistent compared with potassium levels, which was drawn daily for most patients. Although our results are not powered, the findings show that a closer look at electrolytes in this patient population may be warranted.

An analysis of the secondary outcomes is outlined in Table 3. Statistically significant findings were found in the outcomes of hospital length of stay, ICU admission, and the onset of sepsis in the atrial fibrillation cohort compared with the control cohort. However, many of the patients who had atrial fibrillation post-HSCT had more complicated admissions post-HSCT and had an ICU admission or onset of sepsis before the onset of atrial fibrillation, which limited the strength of this finding. Although these findings indicate that patients who had atrial fibrillation post-HSCT are at risk for poorer outcomes, the clinical relevance of this finding cannot be determined.

Limitations

The limitations of this study include the evaluation of only patients who had an autologous HSCT, with the exclusion of those who had an allogeneic HSCT. Allogeneic HSCTs were not included because of the overall increased risk for complications related to this type of transplant.13 Considering the small sample size of our study, their inclusion might have skewed the results.

Our patient population of only those undergoing autologous HSCT gave us a sample size of 275 patients, with a 10.2% incidence of atrial fibrillation. Such a low incidence, with only 28 patients having newly developed atrial fibrillation, makes our sample size too small to reach power in our findings.

Additional limitations include the retrospective nature of this study, with all data being collected by retrospective chart review. Not all patients had thorough cardiac monitoring during their hospital stay, potentially leading to underreporting of atrial fibrillation. At the time of this study, no standard existed for electrolyte monitoring and replacement protocol at our institution. This resulted in inconsistent reporting and replacement of electrolytes in the patients during their admission.

Although the findings were significant in the analysis of secondary outcomes regarding length of stay, ICU admission, and the onset of sepsis, our conclusions are limited by confounding factors.

We hope that future larger, prospective studies will further analyze the impact of electrolyte abnormalities on the onset of atrial fibrillation in this population.

Conclusion

Our findings showed that hypokalemia correlated with the incidence of atrial fibrillation in patients after autologous HSCT. This supports the implementation of more aggressive electrolyte monitoring and replacement protocols in this patient population. This study also supports the consideration of higher electrolyte target values for patients after autologous HSCT; for example, targeting a serum potassium level of at least 4 mEq/L.

This study also established that close to 50% of patients who have atrial fibrillation after autologous HSCT will have a recurrence of atrial fibrillation after their initial HSCT admission. This leads us to believe these patients require thorough cardiology workups, including treatment and monitoring regarding their atrial fibrillation after HSCT. Studies with larger sample sizes are needed to support these findings and establish clinical significance between hypokalemia and hypomagnesemia after HSCT and the onset of atrial fibrillation.

Author Disclosure Statement

Dr Schulze, Dr LaPorte, Dr Breikreutz, Dr Meissner, Dr Parameswaran, Dr Raj, and Dr McCaul have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- Feliz V, Saiyad S, Ramarao SM, et al. Melphalan-induced supraventricular tachycardia: incidence and risk factors. Clin Cardiol. 2011;34:356-359.

- Singla A, Hogan WJ, Ansell SM, et al. Incidence of supraventricular arrhythmias during autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2013;19:1233-1237.

- Sureddi RK, Amani F, Hebbar P, et al. Atrial fibrillation following autologous stem cell transplantation in patients with multiple myeloma: incidence and risk factors. Ther Adv Cardiovasc Dis. 2012;6:229-236.

- Tonorezos ES, Stillwell EE, Calloway JJ, et al. Arrhythmias in the setting of hematopoietic cell transplants. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2015;50:1212-1216.

- Arun M, Brauneis D, Doros G, et al. The incidence of atrial fibrillation among patients with AL amyloidosis undergoing high-dose melphalan and stem cell transplantation: experience at a single institution. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2017;52:1349-1351.

- Peres E, Levine JE, Khaled YA, et al. Cardiac complications in patients undergoing a reduced-intensity conditioning hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2010;45:149-152.

- Fatema K, Gertz MA, Barnes ME, et al. Acute weight gain and diastolic dysfunction as a potent risk complex for post stem cell transplant atrial fibrillation. Am J Hematol. 2009;84:499-503.

- Steuter JA, Villanueva MLH, Loberiza FR, et al. Factors affecting the development of atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter (AF/AFL) following autologous hematopoietic SCT (auto-HSCT). Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013;48:963-965.

- Khan AM, Lubitz SA, Sullivan LM, et al. Low serum magnesium and the development of atrial fibrillation in the community: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2013;127:33-38.

- Krijthe BP, Heeringa J, Kors JA, et al. Serum potassium levels and the risk of atrial fibrillation: the Rotterdam Study. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168:5411-5415.

- Hoppe LK, Muhlack DC, Koenig W, et al. Association of abnormal serum potassium levels with arrhythmias and cardiovascular mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2018;32:197-212.

- Philibert D, Desmeules S, Filion A, et al. Incidence and severity of early electrolyte abnormalities following autologous haematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23:359-363.

- Hierlmeier S, Eyrich M, Wölfl M, et al. Early and late complications following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in pediatric patients–a retrospective analysis over 11 years. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0204914.