Symptom Overview and Etiology

Clostridium difficile–related diarrhea is one of the most common types of nosocomial diarrhea in the United States, with an incidence of 15% to 25%.1 Infectious diarrhea resulting from C difficile is a common complication in patients undergoing hematopoietic stem-cell transplant (HSCT), with higher rates in those undergoing allogeneic than autologous HSCT (12%-18% vs 6%-8.5%, respectively).2-4

Higher rates in patients undergoing allogeneic HSCT may be explained by many factors, including, but not limited to, prolonged hospitalization, myeloablative chemotherapy, longer periods of impaired immunity, and increased antimicrobial treatment exposure.2,3

Cytotoxic chemotherapy agents used as part of HSCT conditioning regimens represent an important risk factor for C difficile infection resulting from altered gastrointestinal (GI) mucosa and increased apoptosis of intestinal crypt cells.1 The use of these medications causes mucosal damage and local inflammation, creating an environment that facilitates the binding and internalization of C difficile infection toxins by intestinal cells, and ultimately leading to the development of C difficile infection. It is interesting to note that the onset of C difficile infection in patients undergoing autologous HSCT occurs much earlier than in allogeneic HSCT recipients (median, 6.5 days vs 33 days post–stem-cell infusion).4

Treatment Options

Historically, the treatment of C difficile infection has been stratified based on the severity of the patient’s condition, as determined by the degree of leukocytosis and elevation in serum creatinine.1 HSCT recipients often undergo treatment with myeloablative chemotherapy regimens during induction and conditioning that suppress the immune system and cause prolonged neutropenia. Therefore, white blood cell count may not be a reliable marker for the severity of C difficile infection in this patient population. Wang and colleagues demonstrated that white blood cell count, as well as serum creatinine levels, do not correlate with mortality outcomes and are not predictive of C difficile infection severity in patients with cancer.5

The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) has issued guidelines for the management of C difficile infection, but these guidelines are not specific for patients undergoing HSCT and do not address this patient population.6 In light of the increased risk for morbidity and mortality associated with C difficile infection, consider empiric treatment with antimicrobial agents in HSCT recipients who have unexplained, new-onset diarrhea (ie, ≥3 unformed stools in a 24-hour period).6 If possible, discontinue or limit treatment with systemic antibiotics that are associated with the development of C difficile infection.

In practice, treatment is initiated while testing is pending, although the IDSA guidelines do not specifically recommend it. Frequently, diarrhea in HSCT recipients may coincide with the onset of mucositis after high-dose myeloablative chemotherapy and radiotherapy.1

In view of overlapping symptoms between noninfectious diarrhea and C difficile infection, treatment should be continued until infectious etiology is ruled out by negative stool studies. Furthermore, allogeneic HSCT recipients are at risk for acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) during the engraftment period. Whereas symptoms of intestinal GVHD often resemble those of C difficile infection (ie, secretory diarrhea, fever, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain), a confirmatory biopsy is needed to definitively diagnose GVHD.7

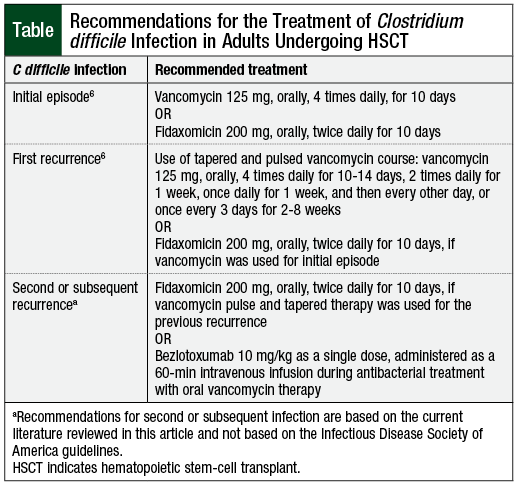

An initial episode of C difficile infection should be treated with oral vancomycin or with fidaxomicin, according to the IDSA guidelines (Table).6 Although both agents are equally efficacious, fidaxomicin is associated with decreased C difficile infection recurrence rates (15.4% vs 25.3%; P = .005) compared with vancomycin.8

The incidence of adverse events, such as mild GI symptoms, is similar for both treatment options.8 For recurrent episodes of C difficile infection, prolonged and/or tapered and pulsed vancomycin therapy should be considered.6 Fidaxomicin may also be used for recurrent C difficile infection in the setting of initial episode treatment with vancomycin.6

Despite similar efficacy and safety, fidaxomicin offers several advantages over vancomycin, including twice-daily dosing, prolonged postantibiotic effect, and a narrow spectrum of activity.9 In addition, unlike vancomycin, fidaxomicin causes minimal inhibition of normal colonic microbiota and decreases overgrowth of vancomycin-resistant Enterococci and Candida species.9

Therefore, fidaxomicin may be a better first-line option in patients at high risk for recurrence and complications resulting from C difficile infection, such as HSCT recipients. Currently, a 10-day course of fidaxomicin is approximately 3 times more expensive than vancomycin, and submission of a prior authorization may be required in the outpatient setting.9

The novel agent bezlotoxumab, a human monoclonal antibody designed to target C difficile toxin B, may be considered as an adjuvant therapy for recurrent episodes of C difficile infection.10 Wilcox and colleagues evaluated the safety and efficacy of the addition of bezlotoxumab to oral standard of care antimicrobials for C difficile infection in the MODIFY I and MODIFY II studies. The results of both trials favored bezlotoxumab over placebo, with recurrence rates of 17% versus 28% (in MODIFY I) and 16% versus 26% (in MODIFY II). The incidence of adverse events, such as nausea, headache, fatigue, dizziness, and pyrexia, was similar between both study arms. Overall, 9% of the patients in the bezlotoxumab arm had infusion-related reactions.10

Based on clinical practice experience, the cost of a bezlotoxumab treatment course (ie, administered as a 1-time, 60-minute intravenous [IV] infusion) is reimbursed via the medical benefits in the outpatient setting.

Bezlotoxumab may be considered as an option for patients at high risk for C difficile infection recurrence (ie, age ≥65 years, immunocompromised status, hospitalization, and ≥1 episodes of C difficile infection in the previous 6 months) in addition to vancomycin treatment.10 Conversely, the combination of bezlotoxumab and fidaxomicin does not appear to significantly reduce C difficile infection recurrence rates compared with fidaxomicin monotherapy (15.4% vs 16%-17%).8,10

Oral metronidazole is no longer recommended by the IDSA guidelines for the treatment of C difficile infection in adult populations.6 The use of IV metronidazole may be considered as an option in cases where oral therapy with preferred agents is not feasible, such as in patients with ileus.6

Approximately 20% to 28% of patients have ≥1 recurrences of C difficile infection after initial infection.1,11 The risk for recurrence is particularly high in patients requiring systemic antimicrobial therapy. Oral vancomycin has been investigated as a prophylactic strategy for patients undergoing treatment with systemic antibiotics.11

Carignan and colleagues and Van Hise and colleagues retrospectively evaluated the efficacy of oral vancomycin for the prevention of recurrent C difficile infection.11,12 Both studies showed that oral vancomycin prophylaxis administered simultaneously with systemic antibiotic therapy resulted in a significant reduction in C difficile infection recurrence rates11,12 (4.2% in the treatment arm vs 26.6% in the control arm, P <.001)12. When used for prophylaxis, vancomycin is administered 125 mg orally twice daily for the duration of systemic antimicrobial therapy, plus up to 7 days after the completion of the treatment course.11,12 Currently, no data exist to support the use of oral vancomycin prophylaxis in HSCT recipients who are not concurrently treated with systemic antimicrobial therapy.

The novel agent ribaxamase is a first-in-class experimental betalactamase designed to degrade excess betalactam antibiotics excreted into the small intestine. Ribaxamase has undergone phase 2 clinical trials,13 with a planned phase 1b/2a clinical trial in adults undergoing allogeneic HSCT, according to the manufacturer.14 No phase 3 clinical trials are planned at this point. Ribaxamase is an oral agent that is administered concurrently with IV antimicrobials, with the goal of protecting the gut microbiome and preventing antibiotic-associated side effects, such as C difficile infection.13

C difficile infection prophylaxis with the administration of probiotics in hospitalized patients has been investigated. No current data exist to confirm the benefit of these agents in the oncology population.6 In addition, the use of probiotics in the peritransplant period may be detrimental to patients with a compromised immune system.15,16 Riquelme and colleagues showed that HSCT recipients developed fungemia with common probiotic species.17

A study by Mehta and colleagues showed a positive correlation between probiotic-enriched yogurt use and Lactobacillus acidophilus bloodstream infection in autologous HSCT recipients.16 Based on the lack of efficacy of probiotics and the potential risk for fungal and bacterial infections in the HSCT population, the use of probiotics should be avoided until immune system reconstitution has occurred.

Conclusion

Infectious diarrhea is a frequent complication in patients undergoing HSCT. Prompt recognition of the disease and treatment initiation are imperative in the vulnerable HSCT-recipient patient population. Currently, oral vancomycin and fidaxomicin are recommended by the national IDSA guidelines as first-line therapy for C difficile infection. Several modalities, such as vancomycin pulse therapy, fidaxomicin, or the addition of bezlotoxumab to vancomycin may be used for the treatment of recurrent episodes of C difficile infection. Prophylaxis with oral vancomycin may be considered in patients receiving systemic antimicrobial therapy. Probiotic use is not recommended, because of the potential risk for infections associated with these agents in immunocompromised HSCT recipients.

Author Disclosure Statement

Dr Melnyk has no conflicts of interest to report.

Reference

- Neemann K, Freifeld A. Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea in the oncology patient. J Oncol Pract. 2017;13:25-30.

- Chopra T, Chandrasekar P, Salimnia H, et al. Recent epidemiology of Clostridium difficile infection during hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Clin Transplant. 2011;25:E82-E87.

- Alonso CD, Treadway SB, Hanna DB, et al. Epidemiology and outcomes of Clostridium difficile infections in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:1053-1063.

- Alonso CD, Marr KA. Clostridium difficile infection among hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients: beyond colitis. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2013;26:326-331.

- Wang MS, Evans CT, Rodriguez T, et al. Clostridium difficile infection and limitations of markers for severity in patients with hematologic malignancy. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2013;34:127-132.

- McDonald LC, Gerding DN, Johnson S, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults and children: 2017 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA). Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66:987-994.

- Zeiser R, Blazar BR. Acute graft-versus-host disease: biologic process, prevention, and therapy. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:2167-2179.

- Louie TJ, Miller MA, Mullane KM, et al; for the OPT-80-003 Clinical Study Group. Fidaxomicin versus vancomycin for Clostridium difficile infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:422-431.

- Al Momani LA, Abughanimeh O, Boonpheng B, et al. Fidaxomicin vs vancomycin for the treatment of a first episode of Clostridium difficile infection: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Cureus. 2018;10:e2778. doi:10.7759/cureus.2778.

- Wilcox MH, Gerding DN, Poxton IR, et al; for the MODIFY I and MODIFY II investigators. Bezlotoxumab for prevention of recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:305-317.

- Carignan A, Poulin S, Martin P, et al. Efficacy of secondary prophylaxis with vancomycin for preventing recurrent Clostridium difficile infections. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:1834-1840.

- Van Hise NW, Bryant AM, Hennessey EK, et al. Efficacy of oral vancomycin in preventing recurrent Clostridium difficile infection in patients treated with systemic antimicrobial agents. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63:651-653.

- Kokai-Kun JF, Roberts T, Coughlin O, et al. The oral β-lactamase SYN-004 (ribaxamase) degrades ceftriaxone excreted into the intestine in phase 2a clinical studies. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017;61:e02197-16.

- Synthetic Biologics. Synthetic biologics receives FDA guidance at type C meeting for SYN-004 (ribaxamase) phase 1b/2a clinical trial in allogeneic HCT recipients. January 7, 2020. Press release. www.syntheticbiologics.com/news-media/press-releases/detail/279/synthetic-biologics-receives-fda-guidance-at-type-c-meeting. Accessed February 3, 2020.

- Cohen SA, Woodfield MC, Boyle N, et al. Incidence and outcomes of bloodstream infections among hematopoietic cell transplant recipients from species commonly reported to be in over-the-counter probiotic formulations. Transpl Infect Dis. 2016;18:699-705.

- Mehta A, Rangarajan S, Borate U. A cautionary tale for probiotic use in hematopoietic SCT patients–Lactobacillus acidophilus sepsis in a patient with mantle cell lymphoma undergoing hematopoietic SCT. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013;48:461-462.

- Riquelme AJ, Calvo M, Guzmán AM, et al. Saccharomyces cerevisiae fungemia after Saccharomyces boulardii treatment in immunocompromised patients. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2003;36:41-43.