The management of cancer therapy remains dynamic because dozens of new oral anticancer agents receive US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval or expanded indications each year. Although oral anticancer agents can be convenient treatment options for patients, their unique mechanisms of action lead to adverse effects that are novel and differ from those related to conventional cytotoxic chemotherapy.

Additional challenges to oral anticancer therapies include patient medication adherence, patient self-identification and reporting of side effects, drug–drug and drug–food interactions, and safe medication handling and storage.1,2 As new oral anticancer agents are approved, it is vital that patients are closely monitored to ensure the safety and tolerability of these agents. As medication experts, pharmacists play a critical role in educating and advising members of the cancer care team to optimize the use of oral anticancer agents based on patient-specific factors.1,2

In 2018, the Hematology/Oncology Pharmacy Association (HOPA) developed a practice standard for pharmacists’ role in the management of oral anticancer agents.3 This practice standard describes 4 best practices for pharmacists in providing patient education, which includes developing standardized education materials, a separate education visit with the patient to supplement information provided during the oncologist’s visit, comprehensive medication education that is focused on self-care management of adverse effects, and an assessment of the patient’s knowledge.3 Pharmacist involvement in all 4 of these elements helps patients make informed decisions about their treatment and enhances the care of patients with cancer.

Instances of patient care optimization via the addition of an oncology pharmacist have been widely reported in literature.2,4-6 At the Alvin J. Siteman Cancer Center in Missouri, pharmacists are integrated into the care of patients with solid tumors who are receiving oral anticancer agents. By providing counseling and education on adverse effects and self-management strategies, helping patients navigate copayment assistance programs, and monitoring for medication side effects and recommending dose adjustments, the pharmacists greatly improved patients’ understanding of and satisfaction with their care, while decreasing the workload and improving the workflow of the clinics.2

The benefits of integrating an oncology pharmacist into a clinic have been replicated at the University of North Carolina Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, as well as at other institutions in the United States and abroad.4-6

Medication histories and medication reconciliation are additional areas where pharmacists can significantly affect patient care and improve patients’ quality of life. In a study of pharmacist- and physician-obtained medical histories, fewer errors were made when a pharmacist completed a medication reconciliation, and pharmacists identified significantly higher numbers of medications taken per patient compared with other healthcare professionals.7

Furthermore, the completion of medication histories by a pharmacist has been associated with decreased mortality and readmission rates and fewer delays in drug dispensing than when completed by a physician.8

As a result of the positive impacts that pharmacists can make in patient care, the demand for pharmacy services has increased, and institutions are exploring the use of pharmacy learners to expand pharmacy services via the layered learning practice model.9,10 The benefits of layered learning have been previously described by Bates and colleagues and include the expansion of clinical pharmacy services, accommodating more pharmacy students and residents, engaging pharmacy learners in creating and supporting new clinical services, and optimizing medication use for patients.9-11

In 2011, the University of North Carolina Medical Center implemented a layered learning practice model for patients who were receiving acute care malignant hematology and medical oncology services.9 An attending pharmacist oversaw pharmacy residents and students who provided discharge medication reconciliation and counseling services.

The pharmacy students and residents reached 61 patients in 2 months and intervened on a median of 1.26 medication-related problems in patients with hematologic malignancies and 2.1 medication-related problems in patients with solid tumors.9 This study demonstrated that the implementation of a layered learning practice model in oncology pharmacy services can be used to expand pharmacy care services.9

Considering the request for the expansion of pharmacy services, as well as the growing numbers of pharmacy learners, at Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center (MGHCC) we developed and instituted a postgraduate year 2 (PGY2) oncology pharmacy resident–led medication reconciliation and patient education service for patients with leukemia who were receiving oral anticancer agent therapy.

This pilot program consisted of 1 PGY2 oncology pharmacy resident, 4 Advanced Pharmacy Practice Experience students, and 4 clinical hematology/oncology pharmacists who served as clinical content and operational advisors. The Appendix outlines the standard operating procedure for this pilot program.

The objective of this expanded service was to provide medication reconciliation and patient education services to optimize the care of patients who were initiated with a new oral anticancer agent or who were switching from one oral anticancer agent to another. The purpose of the pilot study was to consider the feasibility of this service and to determine the number of patients for whom the pharmacy students and PGY2 oncology pharmacy resident were able to provide clinical pharmacy services. We also discussed the barriers encountered and characterized the types of interventions made.

Methods

This single-center pilot study of patients with leukemia who were initiated with oral anticancer agents or were switched to a different agent was conducted between September 1, 2019, and January 31, 2020. Patients were included if they met the following criteria: aged >18 years, diagnosed with leukemia, initiated or switched to an oral anticancer agent during the study period, and received care at MGHCC, a 1000-bed academic medical center and outpatient infusion clinic. Patients were excluded if they refused pharmacy services or had altered mental status.

This pilot study was undertaken as a Quality Improvement Initiative at MGHCC, and as such was not formally supervised by the Institutional Review Board per its policies.

Patients with leukemia were identified via one of several methods: notification from a provider via a page or an e-mail, notification via e-mail from the nurse handling the prior authorization for oral anticancer agents, prospective chart review by a PGY2 oncology pharmacy resident, or notification from an inpatient pharmacist via a page or an e-mail.

The oral anticancer agents included bosutinib, dasatinib, enasidenib, gilteritinib, glasdegib, imatinib, ivosidenib, midostaurin, nilotinib, ponatinib, ruxolitinib, and venetoclax. The patients’ diagnoses included acute myeloid leukemia, acute lymphocytic leukemia, chronic myeloid leukemia, mast-cell leukemia, as well as myelodysplastic syndromes and myeloproliferative neoplasms.

The primary outcome measure was to assess the number of patients to whom 1 PGY2 oncology pharmacy resident and 4 pharmacy students were able to provide pharmacy services, which was defined as having received medication reconciliation services, medication education, or both. The secondary outcome measures included determining the number of interventions made by the PGY2 oncology pharmacy resident, characterizing the interventions, and identifying the barriers to the implementation of this service.

Preparation for the Pilot Program

Considerable planning and preparation that started 5 months before the implementation of this pilot program were crucial to ensuring its success. Four hematology/oncology clinical pharmacist preceptors identified 1 physician champion, designed the pilot program proposal, and set up a shadowing day for the PGY2 oncology pharmacy resident to observe the leukemia clinic processes and workflow.

While shadowing the physician champion, the PGY2 oncology pharmacy resident identified potential challenges to making face-to-face contact with patients, such as coordination with clinic staff on patient appointment times and integrating clinic visits into the PGY2 oncology pharmacy resident’s rotation schedule. In addition, the PGY2 oncology pharmacy resident developed and updated a standard operating procedure to serve as a guide for the duties and responsibilities of the pharmacy students and the PGY2 oncology pharmacy resident.

Determining identification strategies for eligible patients with leukemia who were newly initiated with an oral anticancer agent or switched to a different oral agent was vital. The PGY2 oncology pharmacy resident e-mailed the providers and the prior authorization nurse weekly as a reminder to notify the PGY2 oncology pharmacy resident of eligible patients. The PGY2 oncology pharmacy resident also conducted chart reviews of upcoming clinic days to identify patients. The inpatient pharmacists notified the PGY2 oncology pharmacy resident when an eligible admitted inpatient was starting an oral anticancer agent.

As part of the layered learning practice model, pharmacy students conducted medication histories. To orient the pharmacy students to the program, the PGY2 oncology pharmacy resident conducted medication history training sessions for the pharmacy students and served as their primary preceptor. To further supplement pharmacy student learning and minimize variation in the pharmacy services provided, the PGY2 oncology pharmacy resident developed a script, including communication etiquette, for pharmacy students to adhere to while obtaining medication histories.

Finally, in accordance with HOPA’s practice standard and MGHCC institutional guidance, the PGY2 oncology pharmacy resident created or updated patient education documents for 11 oral anticancer agents to supplement the verbal education. These education documents for patients with cancer were developed using the drug’s prescribing information and included details about the drug’s mechanism, dose, administration, side effects, storage, and safe handling. Each education document was reviewed by the preceptors and approved by the physician champion.

The PGY2 oncology pharmacy resident also developed 11 education note templates that detailed the patient encounter, including questions answered; drug–drug interactions that were identified using primary literature, prescribing information, and Lexicomp; drug–food interactions; and time spent with the patient. These notes were placed in the patient chart after the encounter.

After the Start of the Pilot Program

After this pilot program began, several ongoing maintenance tasks were introduced. The PGY2 oncology pharmacy resident continued to e-mail providers each week, detailing the ongoing pilot program and reminders to contact the PGY2 oncology pharmacy resident with any eligible patients.

As workflows were being optimized, the standard operating procedure was continuously updated to reflect changes in pharmacy student training, daily responsibilities, and integration into the clinic’s workflow. In addition, the PGY2 oncology pharmacy resident provided guidance to the inpatient pharmacists so that they would be able to provide these services for patients who were admitted to the hospital.

All the patient education documents and education note templates were saved in a Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act–compliant Dropbox folder provided by MGHCC and were shared with the inpatient pharmacists. Hematology/oncology pharmacy preceptors were available to the PGY2 oncology pharmacy resident throughout the pilot program.

Descriptive statistics were used for data analysis. Dichotomous and categorical variables are reported here as frequencies with percentages. Continuous variables are reported as medians and ranges. Microsoft Excel was used for data analysis.

Results

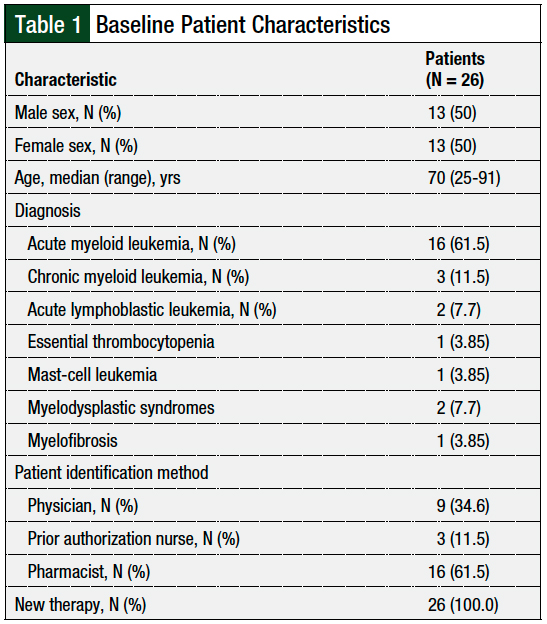

During the pilot study, 28 patients were identified via notification either from a provider, a nurse, an inpatient pharmacist, or a prospective chart review; of these, 26 patients met our study’s inclusion criteria. The reasons for exclusion were refusal of services (N = 1) and altered mental status (N = 1). The patient population included 50% (N = 13) females and 50% (N = 13) males, with a median age of 70 years. Table 1 outlines the baseline patient characteristics.

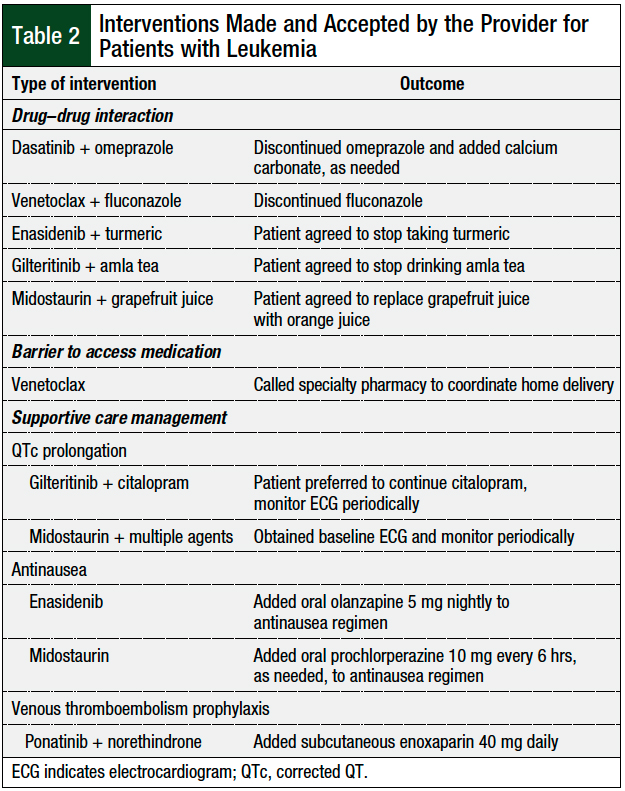

Per patient, the median number of interventions made was 3 (range, 1-4). In the 26 patients, the interventions included the completion of medication history and reconciliation (N = 26; 100%), providing medication education (N = 26; 100%), the identification of drug–drug interactions (N = 5; 19.2%), the optimization of supportive care (N = 5; 19.2%), and the identification of barriers to medication access (N = 1; 3.8%).

A total of 11 interventions required provider input and discussion, and all 11 interventions were accepted by the provider and involved the discontinuation of an interacting medication, increased cardiac monitoring, or additional supportive care measures. The details of the interventions are shown in Table 2.

A median of 20 minutes (range, 15-70 minutes) was spent with each patient to provide medication education. This amount of time does not include the time spent conducting medication histories, medication reconciliation, discussions with the provider, or the documentation of activities.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first pilot study to evaluate the feasibility of a pharmacy resident–led medication reconciliation and patient education program in a clinic that manages adults with leukemia. As more oral anticancer agents are approved by the FDA, the need for patient education becomes critical to enable patients to identify and manage medication side effects while receiving treatment at home.

This pilot study implemented a pharmacy resident–led medication reconciliation and patient education service to improve treatment adherence, optimize supportive care, and educate patients who are receiving oral anticancer agents by informing them of potential side effects, management strategies, and when to reach out to their providers.

One of the largest barriers we encountered was the absence of a consistent method to identify eligible patients, because our institution’s electronic medical record (EMR) does not have a report that pulls in new oral anticancer agent prescriptions. This barrier resulted in reliance on the notification about eligible patients from other members of the cancer care team and prospective chart reviews. In the future, it may be helpful to develop an EMR report that could be run weekly to identify eligible patients.

Furthermore, it was difficult to limit the patient education encounter to matters pertaining only to the oral anticancer agent, because many patients asked for help with insurance, prior authorizations, and specialty pharmacy delivery coordination, which were outside the scope of this pilot study. Troubleshooting these matters also increased the amount of time that the PGY2 oncology pharmacy resident spent with patients. In the future, the patient encounter could be expanded to include an overview of specialty pharmacy and insurance navigation to answer questions pertaining to these topics in a proactive way.

Because many of the barriers we encountered stem from time constraints, it would be beneficial to have a dedicated full-time oncology pharmacist or pharmacy extenders at the leukemia clinic. This would provide an opportunity to review patients being seen at the clinic, identify the initiation of new oral anticancer agents, and provide supportive-care management services.

The pharmacy department at the University of North Carolina was awarded a grant to support a full-time oncology pharmacist who would be integrated into the oncology clinic to initiate a supportive care program.4 This pharmacist was available in the clinic Monday through Friday during normal clinic hours of operation, which enhanced pharmacist visibility and allowed for full integration into the clinic’s services.

Many of the layered learning techniques and patient care activities used in our pilot study were adapted from earlier reports of successful implementations of ambulatory care services by clinical pharmacists at other sites in the United States and abroad.9,10 Our experience using the layered learning model showed that this structure is feasible, but that the model is amenable to optimization.

Four pharmacy students rotated monthly during the span of our pilot study, which required that the PGY2 oncology pharmacy resident take time out of rotation to train students each month. In the future, it may be more efficient to have 1 to 2 longitudinal pharmacy students involved throughout the year to decrease the time required for orientation and training.

A longitudinal experience for pharmacy students would also allow for a comprehensive preceptor experience for the PGY2 oncology pharmacy resident because the resident would experience the leadership role of developing objectives for the student, the evaluation of student work, and providing written and verbal feedback. This type of layered learning practice model can help to expand patient care and clinical services.9,10

At the Durham Veterans Affairs Health Care System in North Carolina, PGY1 and PGY2 residents use a 4-step model to orient students, outline expectations for activities, develop resources and evaluation tools, and provide written and verbal evaluation of the students.11 Loy and colleagues have reported a potential for providing quality precepting opportunities for residents, enhancing student learning, and improving preceptor efficiency.11

Finally, our pilot study did not examine the impact of pharmacy services on patient outcomes, such as quality of life, response to treatment, and patient understanding, which are important aspects of demonstrating the value of pharmacists.

Ma and colleagues evaluated pharmacist interventions and patient outcomes in a pharmacist-led outpatient palliative care practice.12 The pharmacist participated in 84 new patients with cancer visits and 135 follow-up patient visits over the course of 1 year, which resulted in a statistically significant change in pain score at the patients’ third visit with the pharmacist.12

Another study by Muluneh and colleagues assessed the medication adherence rates and clinical outcomes of a pharmacist-led oral anticancer agent management program.13 Between September 2014 and June 2015, clinical pharmacists working under a collaborative practice agreement educated all patients receiving oral anticancer agents either in the clinic or via a telephone call. This pharmacist-led oral anticancer agent management program led to an improvement in patients’ understanding of their oral anticancer agents, increased medication adherence rates, and significantly improved major molecular response rates.13

The wide variety of skills and deep breadth of knowledge that oncology pharmacists have provides the oncology care team with a unique perspective on cancer care. The pharmacist is one of the few team members who understand the safety, efficacy, operational, and financial components surrounding the medication aspect of patient care.1 As the role of clinical pharmacists in patient care expands and evolves, the pharmacist, pharmacy students, and pharmacy residents are uniquely positioned to provide care and show value in all dimensions of a patient’s treatment course.14

Our experience demonstrates a stepwise approach to the development and implementation of a new pharmacy service. This service was led by pharmacy extenders without the use of additional full-time equivalents that allowed the pharmacy team to provide services to areas that previously did not have a pharmacy presence. A substantial amount of time was dedicated to creating education materials and templates, training pharmacy students, educating patients, and communicating with providers, which were critical to our success as we demonstrated that pharmacy extenders can be a sustainable way to expand clinical pharmacy services.

Modifications to our pilot program to streamline care and increase efficiency include using longitudinal pharmacy students to decrease the amount of time training students, employing an oncology pharmacist full-time in clinic, and training additional pharmacists to provide these services. A possible area of expansion in the future is to have regular, scheduled follow-up visits or telephone check-ins with patients after the start of oral anticancer agents.

In our pilot program, we provided medication education and supportive care management recommendations to patients before starting therapy or after they had only received 1 dose of treatment. A structured oral anticancer agent oncology pharmacist care continuum with monthly and as-needed telephone follow-up visits to address medication adherence and side effects can contribute to safe and optimal patient care, and would further strengthen the role of the oncology pharmacist in the clinic.

Limitations

This pilot study has several limitations. We were not able to reach all the patients who were eligible to receive pharmacy services, because of the variability in effectiveness of the patient identification methods. Several patients who were newly started with or switched to an oral anticancer agent might have been missed if previous notes were not updated before chart review or if the PGY2 oncology pharmacy resident was not contacted.

In addition, because the PGY2 oncology pharmacy resident did not work side by side with the providers and was not physically present in the clinic, the impact of pharmacy services on patient care may not have been fully realized.

Furthermore, our pilot study addressed the number of patients reached, but not the clinical impact of a pharmacist on patients’ quality of life or outcomes. One study examined the impact of patient education by a pharmacist on complete response rates or quality-of-life scores.13 Because there is mounting pressure on pharmacists to demonstrate their value to the healthcare team, it becomes imperative to track closely and draw correlations between pharmacist intervention and health outcomes.

Finally, our pilot study only spanned 5 months and included 26 patients who received medication reconciliation and medication education services for leukemia at MGHCC. This is a small sample size over a short period of time and is specific to MGHCC and to the population of patients with leukemia.

Conclusion

Oncology pharmacy services are a vital component of the treatment and safety of patients with leukemia. This is the first pilot study to assess the feasibility of using pharmacy students and a PGY2 oncology pharmacy resident to implement a new medication reconciliation and patient education service. This pilot study demonstrates the ability of pharmacy students and a PGY2 oncology pharmacy resident to integrate into the initial medication education and reconciliation facet of patient care. When pharmacy personnel resources are limited, the layered learning practice model is an approach that pharmacy residency programs can use to expand services into clinics that were previously unreached by pharmacy.

Author Disclosure Statement

Dr Jia, Dr Signorelli, Dr Luk, Dr Kim, and Dr Blouin have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- Holle LM, Boehnke Michaud L. Oncology pharmacists in health care delivery: vital members of the cancer care team. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10:e142-e145.

- Stein J, Mann J. Specialty pharmacy services for patients receiving oral medications for solid tumors. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2016;73:775-796.

- Mackler E, Segal EM, Muluneh B, et al. 2018 Hematology/Oncology Pharmacist Association best practices for the management of oral oncolytic therapy: pharmacy practice standard. J Oncol Pract. 2019;15:e346-e355.

- Valgus JM, Faso A, Gregory KM, et al. Integration of a clinical pharmacist into the hematology–oncology clinics at an academic medical center. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2011;68:613-619.

- Shah S, Dowell J, Greene S. Evaluation of clinical pharmacy services in a hematology/oncology outpatient setting. Ann Pharmacother. 2006;40:1527-1533.

- Periasamy U, Mohd Sidik S, Rampal L, et al. Effect of chemotherapy counseling by pharmacists on quality of life and psychological outcomes of oncology patients in Malaysia: a randomized control trial. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2017;15:104.

- Reeder TA, Mutnick A. Pharmacist- versus physician-obtained medication histories. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2008;65:857-860.

- Splawski J, Minger H. Value of the pharmacist in the medication reconciliation process. P T. 2016;41:176-178.

- Bates JS, Buie LW, Amerine LB, et al. Expanding care through a layered learning practice model. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2016;73:1869-1875.

- Bates JS, Buie LW, Lyons K, et al. A study of layered learning in oncology. Am J Pharm Educ. 2016;80:68.

- Loy BM, Yang S, Moss JM, et al. Application of the layered learning practice model in an academic medical center. Hosp Pharm. 2017;52:266-272.

- Ma JD, Tran V, Chan C, et al. Retrospective analysis of pharmacist interventions in an ambulatory palliative care practice. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2016;22:757-765.

- Muluneh B, Schneider M, Faso A, et al. Improved adherence rates and clinical outcomes of an integrated, closed-loop, pharmacist-led oral chemotherapy management program. J Oncol Pract. 2018;14:e324-e334.

- Gatwood J, Gatwood K, Gabre E, Alexander M. Impact of clinical pharmacists in outpatient oncology practices: a review. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2017;74:1549-1557.