Nausea and vomiting are common adverse effects of chemotherapy that continue to affect patients’ quality of life negatively, despite the use of prophylactic medications.1 Olanzapine is an oral atypical antipsychotic drug that has been used for breakthrough and refractory chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV)2-4; guidelines have recently incorporated olanzapine into their first-line algorithms for the prevention of acute and delayed CINV in patients receiving intravenous highly emetogenic chemotherapy (HEC) or moderately emetogenic chemotherapy (MEC).5,6

The American Society of Clinical Oncology and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) recommend olanzapine as part of a 4-drug regimen that includes a neurokinin-1 (NK-1) receptor antagonist, a 5-hydroxytryptamine-3 (5-HT3) receptor antagonist, and dexamethasone in patients receiving HEC.5,6 The NCCN also recommends the use of olanzapine in conjunction with palonosetron and dexamethasone for HEC and MEC regimens as part of a 3-drug combination.6

Palonosetron is a second-generation 5-HT3 receptor antagonist that has a longer duration of action, and possesses additional mechanisms that may help decrease the rate of CINV, specifically delayed CINV compared with other 5-HT3 receptor antagonists.7 However, the cost of palonosetron may prohibit institutions from adding it to the formulary for inpatient use.

Dexamethasone’s use as a CINV prophylaxis medication may also be limited because of the adverse effects associated with its short-term use. The NCCN guidelines on antiemesis have recently decreased the recommended dose of dexamethasone on day 1 from 20 mg to 12 mg, and now include a recommendation to individualize dexamethasone dosing, including a consideration for the elimination of dexamethasone on subsequent days for non–cisplatin-containing regimens.6

Single-day high-dose melphalan is a conditioning regimen for patients with multiple myeloma undergoing autologous hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation (HSCT). Melphalan can result in significant nausea and vomiting in the acute and delayed treatment settings.6 The most recent NCCN guidelines consider melphalan as highly or moderately emetogenic at doses ≥140 mg/m2 and <140 mg/m2, respectively, although earlier versions considered it to be only moderately emetogenic, regardless of dose.6

Although the use of olanzapine for CINV prophylaxis has been studied in a variety of patient populations,8-10 its use in patients receiving a conditioning regimen for HSCT warrants further investigation, because of paucity of data in this patient population. The available literature on olanzapine in patients who have had HSCT does support its use.11,12 A randomized prospective study by Nakagaki and colleagues showed that olanzapine was effective in controlling breakthrough CINV in patients who have had HSCT.11 More recently, Clemmons and colleagues published their positive findings of using olanzapine as part of a 4-drug CINV prophylaxis regimen in patients undergoing HSCT.12

Based on guideline updates,5,6 favorable data on the use of olanzapine in the transplant and nontransplant settings,8-11 as well as our clinical experience with a significant need for rescue medications with our prophylactic CINV regimen, a pharmacy-driven change in our CINV prophylaxis protocol was implemented at our institution at Houston Methodist Hospital, Texas Medical Center, for patients with multiple myeloma who were receiving single-day high-dose melphalan before autologous HSCT.

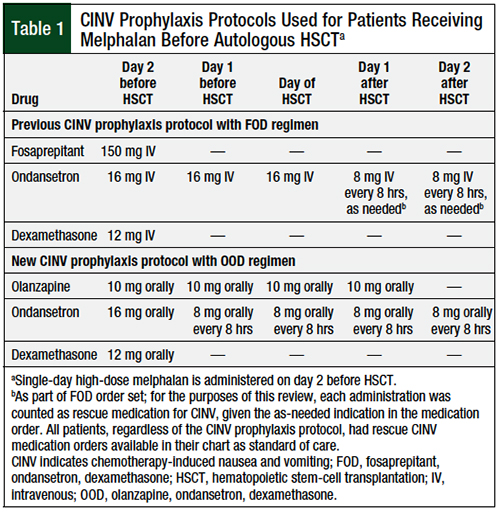

The new protocol, which was put into effect in April 2017, consists of a regimen of olanzapine, ondansetron, and dexamethasone (OOD), in which all medications are preferentially administered orally. Ondansetron administration is scheduled around the clock to mimic the longer duration of action of palonosetron, because the latter was not available in the inpatient setting at our institution. Before the implementation of this protocol, a prophylaxis regimen consisting of fosaprepitant, ondansetron, and dexamethasone (FOD) had been used, in which all medications were preferentially administered intravenously. At the time of implementation, our institution had approximately 60 to 70 patients with multiple myeloma who received treatment, annually, in our 15-bed bone marrow transplant unit. Almost all the patients with multiple myeloma who received single-day high-dose melphalan at our institution had additional risk factors that would necessitate the addition of an NK-1 receptor antagonist to their CINV prophylaxis.

At our institution, treatment with ondansetron and dexamethasone alone in this patient population resulted in unacceptable rates of delayed nausea; hence, even before the most recent NCCN guideline updates that now classify melphalan ≥140 mg/m2 as HEC, the longstanding practice had been to use empirically the FOD regimen in such patients.

The objective of this retrospective review was to compare the efficacy and safety of the newly instituted OOD regimen versus the historical FOD regimen in patients with multiple myeloma who are receiving single-day high-dose melphalan before autologous HSCT.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective review of a practice change that was implemented in patients with multiple myeloma who were receiving single-day high-dose melphalan as a conditioning regimen before autologous HSCT. The specific protocols used at our institution for the FOD and OOD regimens are shown in Table 1. No other protocol changes were implemented during the period reviewed.

As part of our institution’s standard of care, bone marrow transplant pharmacists ensure that rescue CINV medication orders are available in each patient’s chart. The selection of rescue medication is individualized and is not part of the FOD or OOD order sets (with the exception of as-needed ondansetron orders in the FOD regimen on day 1 and day 2 posttransplant; Table 1). Providers are available at all times if additional orders for rescue CINV medications are needed.

The rescue antiemetic medications evaluated in this review included dexamethasone, haloperidol, lorazepam, metoclopramide, olanzapine, ondansetron, prochlorperazine, promethazine, and scopolamine.

We obtained the electronic medical records (EMRs) for all the patients who received melphalan and fosaprepitant between June 1, 2016, and March 31, 2017, through an institutional pharmacovigilance system. We chose the start date of June 1, 2016, because it coincides with the date that our institution’s current EMR system went online. We pulled the EMRs for all patients who received melphalan and olanzapine between April 1, 2017, and March 31, 2018, from the same system. One author was responsible for manually reviewing all the patients’ EMRs to ensure the accuracy of the administratively pulled data.

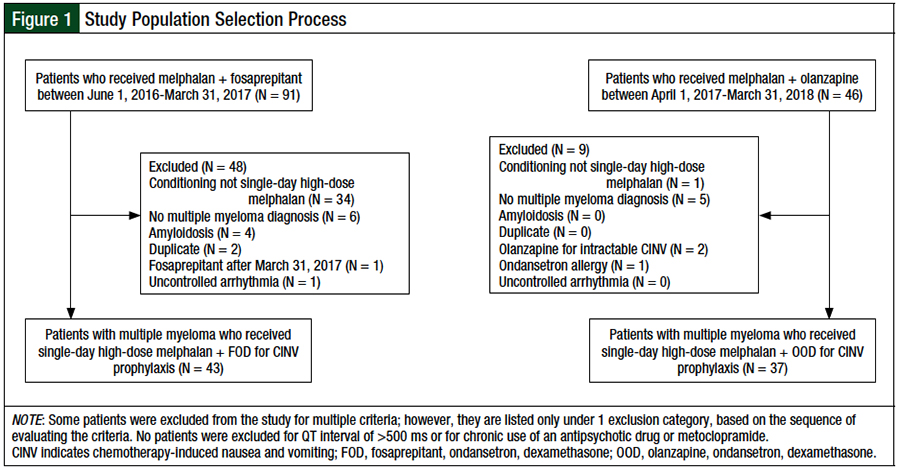

Patients were included in this review if they had a diagnosis of multiple myeloma and received single-day high-dose melphalan for autologous HSCT (Figure 1). Patients were excluded from the study if they had a diagnosis of amyloidosis, had a corrected QT interval of >500 ms, as measured by an electrocardiogram before autologous HSCT, had chronic antipsychotic drug or metoclopramide use, or had uncontrolled arrhythmia.

The study’s primary end point was the proportion of days requiring rescue medications for CINV within 7 days (ie, 168 hours) of melphalan administration. The secondary end points included the proportion of patients requiring rescue medications for CINV in the acute (0-24 hours), delayed (24-120 hours), and very-delayed (120-168 hours) periods.

We charted the distribution of days requiring rescue medications for CINV, and performed comparisons for length of hospitalization and time to engraftment. Engraftment was defined as the first of 3 consecutive days with an absolute neutrophil count of ≥500 cells/µL.

We also evaluated adherence to each protocol to assess the feasibility of the new OOD regimen, and to ensure that the differences in the proportion of days requiring rescue medication for CINV are not a result of differences in adherence to protocol. Adherence was evaluated by looking at the percentage of medications administered as scheduled, with the FOD regimen having 5 medications and the OOD regimen having 18 medications that needed to be given at scheduled times (see Table 1 for our institutional dosing schemes).

To evaluate safety as an end point, one author was responsible for reviewing all the patients’ EMRs for the entire duration of their inpatient HSCT-related stay to determine if any safety events related to receiving the FOD or OOD regimen were documented in the chart. Each safety event noted was discussed with a second author, who was involved in the daily care of the specific patient, to determine if the cause of the event was related to the CINV regimen received.

To investigate whether the OOD regimen leads to a decreased proportion of days requiring rescue medication for CINV compared with the FOD regimen, we used a 2-tailed Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

Based on previous observations, the expected proportion of days requiring rescue medication for CINV in the FOD cohort was estimated to be 0.714 (5 of 7 days). Based on the available data from our institution, the anticipated sample size for the FOD cohort was 40 patients, and the OOD cohort was projected to have 20 patients. Although not conventional for retrospective studies, a Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to determine that the model parameters would provide 80% power to detect a decrease of 50% in the proportion of days requiring rescue medication for CINV in the OOD cohort.

The secondary analysis included the proportion of patients requiring rescue medication for CINV by treatment arm in the acute, delayed, and very-delayed periods after receiving melphalan. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc; Cary, NC); statistical significance was defined as P <.05. The P values were estimated by Monte Carlo simulations.

Results

The selection process for the study population is shown in Figure 1. A total of 137 patient charts were screened for eligibility. After the inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied, 43 and 37 patients were included in the FOD and OOD cohorts, respectively. The main reason for study exclusion was the receipt of a conditioning regimen other than single-day high-dose melphalan.

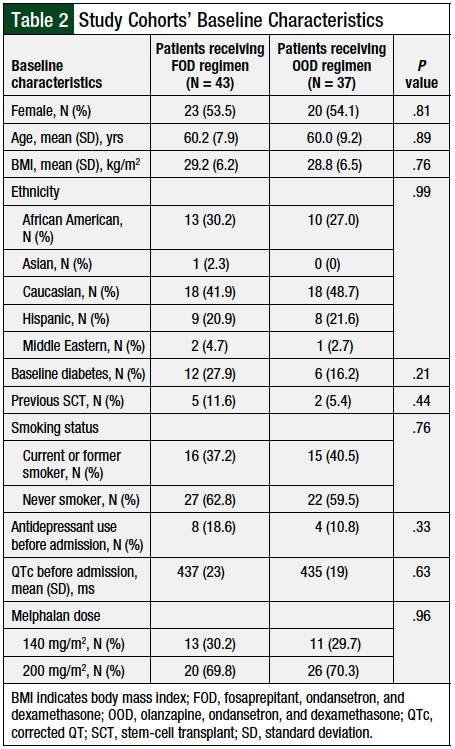

No significant differences were found in the baseline characteristics of the 2 study cohorts (Table 2). The majority of patients were female, with a mean age of 60 years and a mean body mass index of 29 kg/m2, who self-identified as Caucasian. The majority (70.1%) of patients received melphalan at the 200-mg/m2 dose, whereas the remaining patients (29.9%) received melphalan at the 140-mg/m2 dose. The distribution of melphalan doses between the 2 cohorts was similar (P = .96).

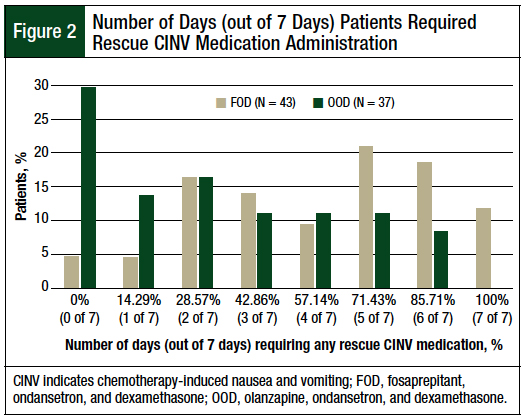

A significant difference was found between the median number of days in which patients in the FOD and OOD cohorts required rescue medication for CINV within 7 days after receiving melphalan (FOD cohort, 5 of 7 days [71.43%] vs OOD cohort, 3 of 7 days [42.86%]; P = .0013). Almost 30% of patients in the OOD cohort required no rescue medication for CINV within 7 days after receiving melphalan (Figure 2). The distribution of patients by the total number of days in which they required rescue medication for CINV is shown in Figure 2.

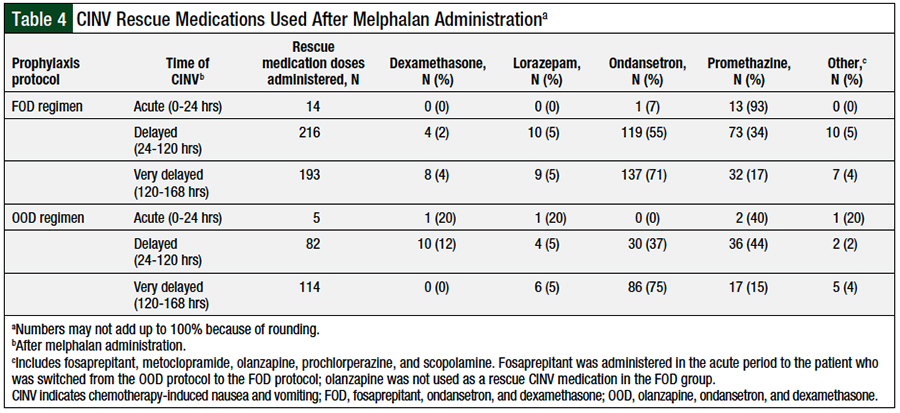

The use of rescue medication for CINV was assessed during the acute, delayed, and very-delayed periods after the administration of melphalan and is presented as the distribution of patients requiring rescue medications for CINV in each period assessed (Table 3), and as the distribution of specific rescue medications for CINV administered in each period (Table 4). Significantly more patients in the FOD cohort required rescue medication for CINV at all periods that were analyzed.

Overall, 1 patient (4.3%) had a significant adverse effect that was thought to be related to treatment with olanzapine. The patient was an elderly female who weighed less than 50 kg and had had a previous transplant. She was switched from the OOD to the FOD prophylaxis protocol as a result of hypotension that presented after she received the first dose of olanzapine. Her hypotension subsequently resolved without a need for any medical intervention.

Daily morning blood glucose levels from day of melphalan administration (ie, 2 days before transplant) through day 4 after transplant were evaluated for the entire study cohort, as well as for 2 subgroups based on patients with or without a diagnosis of diabetes at baseline. No significant differences were noted for daily morning blood glucose levels (data not shown). Drowsiness, which is a side effect that has been reported with the use of olanzapine for the treatment of CINV,6,8 could not be evaluated through our chart review.

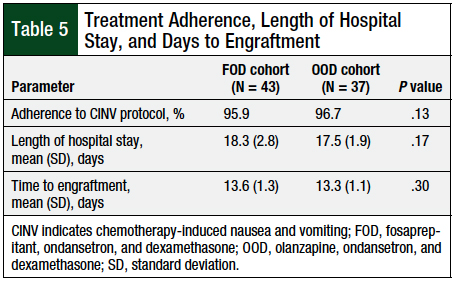

The patients’ median length of hospital stay was approximately 17 days for both cohorts, with a range of 14 to 28 days for FOD, and 15 to 23 days for OOD. There was no significant difference between the mean lengths of hospital stay between the 2 cohorts (Table 5).

The median time to engraftment was approximately 13.5 days for both cohorts, with a range of 11 to 19 days for FOD, and 11 to 16 for OOD. There was no significant difference between the mean time to engraftment between the 2 cohorts (Table 5).

The rates of adherence to the CINV prophylaxis protocols were 95.9% and 96.7%, respectively, for the FOD and OOD protocols (Table 5), when evaluating the percentage of medications administered.

Discussion

Olanzapine is now recommended as a first-line option for CINV prophylaxis by consensus guidelines.5,6,13 However, there is still a paucity of data evaluating olanzapine’s role in patients receiving conditioning regimens before HSCT. The majority of the studies evaluating olanzapine for CINV prophylaxis were conducted in patients with solid malignancies.8,10,14

The study by Clemmons and colleagues examined the addition of olanzapine to fosaprepitant, ondansetron, and dexamethasone in patients receiving single-day and multiday HSCT regimens, and showed that the addition of olanzapine significantly improved clinically relevant outcomes in this patient population.12 This randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study is the first of its kind to evaluate using olanzapine for CINV prophylaxis in patients undergoing HSCT.12 Additional studies to verify these findings, including retrospective reviews such as ours, that also help determine the feasibility of new protocols, are required to find the optimal role, dose, and dosing schedule of olanzapine when used for the prevention of CINV with HSCT conditioning regimens.

The results of this retrospective review show that treatment with an olanzapine-based 3-drug CINV prophylaxis regimen results in a significant decrease in the number of days requiring administration of rescue medication for CINV within 7 days after receiving melphalan compared with a fosaprepitant-based CINV prophylaxis regimen.

There was a decrease in the use of rescue medication for CINV at all time periods assessed, including the acute, delayed, and very-delayed periods. This decrease in the use of rescue medication did not come at the expense of any safety parameters assessed as part of this retrospective review.

The 1 patient who had to be switched from the OOD to the FOD prophylaxis protocol had risk factors for oversedation with olanzapine, including age and weight. Although it was not determined to be a causative factor here, another important consideration when evaluating patients for olanzapine use should be drug–drug interactions, because it is common for patients who undergo HSCT to receive other sedating medications, including and aside from antiemetic drugs.

After evaluating our findings and the most recent guideline recommendations for antiemesis, our institution’s protocol has been amended to allow dose decreases from 10 mg to 5 mg for patients who are elderly or who are at risk for oversedation.6,14

Our findings are in alignment with another single-institution retrospective study that was published after our switch to the OOD regimen.15 In their study, Trifilio and colleagues showed that an olanzapine-based regimen significantly reduced acute and delayed CINV compared with an aprepitant- or fosaprepitant-based regimen in patients with multiple myeloma who received single-day high-dose melphalan before autologous HSCT. The dosing used in that study was different from ours (olanzapine 5 mg twice daily vs 10 mg daily, respectively), and the amount of steroid used was significantly higher (intravenous 125-mg methylprednisolone vs oral 12-mg dexamethasone on the day of melphalan administration, respectively).15

Documentation limitations kept us from evaluating the valuable efficacy and safety end points that Trifilio and colleagues were able to capture. However, the prevalence of studies evaluating the methods to improve EMR documentation practices likely means that detailed information on each episode of nausea for every patient may not be readily available to many institutions.16-18 Analyzing the use of objective data only to evaluate the efficacy of a protocol change, as was done in our review, may be of value to other systems as well.

An interesting similarity between our review and the study by Trifilio and colleagues is the evaluation of CINV observed more than 120 hours after receiving melphalan.15 The 2 studies have come up with this end point independently, which indicates similar experiences at different institutions and a significant need for the development of optimal CINV prophylaxis regimens that effectively prevent these very delayed CINV episodes.

Our findings are also significant from a potential cost-savings standpoint. At the time of this retrospective review, the reported average wholesale price (AWP) for a 150-mg vial of reconstituted fosaprepitant was $401.56, whereas the AWP of a 10-mg tablet of olanzapine was between $0.15 and $19.92, based on the manufacturer. Although it is important to note that hospital purchasing prices may differ significantly, the cost-savings realized by our institution, based on our own purchasing prices of all CINV medications included in the FOD and OOD regimens, were significant.

Limitations

The limitations of this study include its retrospective nature and the small sample size.

The differences in ondansetron dosing on day 1 before transplant and the day of transplant for the FOD versus OOD protocols need to be acknowledged as a potential confounder of this study’s results. However, the intention of the OOD protocol implementation was to improve our patient outcomes and not necessarily to serve as a perfect comparator to the FOD protocol, and we believe that the OOD protocol has served its intent.

The use of an end point that is not complete response may also be seen as a limitation, because our findings cannot be directly compared with the findings of other studies of CINV prophylaxis. The unconventional end point of the proportion of days requiring rescue CINV medication administration was chosen for our study. Our reasoning was that to use complete response as an end point, we would need complete documentation of every episode of nausea and vomiting in the EMR. However, using the proportion of days requiring rescue CINV medication administration as an end point is more objective and reliable, especially in the setting of a retrospective study design. The use of the proportion of days requiring rescue CINV medication administration allows for the collection of data through evaluating the electronic medication administration record either manually or through a data pull.

Other limitations include the lack of comparator data on the number of emesis episodes, patient satisfaction and quality-of-life scores, and oral intake of food and fluids during hospitalization.

Safety events had to be reviewed manually in EMR notes, which is another significant limitation that needs to be highlighted. Such end points would be appropriate for evaluation in future prospective studies.

Conclusion

The results of this retrospective review suggest that a 3-drug CINV prophylaxis regimen that includes olanzapine, ondansetron, and dexamethasone leads to a significant reduction in the number of days that require rescue medication for CINV compared with a regimen that includes fosaprepitant, ondansetron, and dexamethasone in patients with multiple myeloma who are receiving single-day high-dose melphalan conditioning before autologous HSCT. Our group believes that the combination of olanzapine, ondansetron, and dexamethasone represents a cost-effective and feasible CINV prophylaxis regimen for this patient population. The results of this study should be investigated in a randomized clinical trial.

Author Disclosure Statement

Dr Ramos is an advisory board member for Novartis and Celgene, and has received research support from Tessa Therapeutics. Dr Carrum is a member of the Institutional Review Board for US Oncology. Dr Ekinci, Dr Cox, Dr Ensor, Dr McLean, Dr Lulla, and Dr Kamble have no conflicts of interest to report.

Correction

In the print version of this article, the last part of the sentence ending with “the longstanding practice had been to use empirically the FOD regimen in such patients, and use dexamethasone only on day 1 post-HSCT,” should have read “the longstanding practice had been to use empirically the FOD regimen in such patients.” This error has been corrected online and in the PDF.

References

- Bloechl-Daum B, Deuson RR, Mavros P, et al. Delayed nausea and vomiting continue to reduce patients’ quality of life after highly and moderately emetogenic chemotherapy despite antiemetic treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4472-4478.

- Chiu L, Chow R, Popovic M, et al. Efficacy of olanzapine for the prophylaxis and rescue of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24:2381-2392.

- Navari RM. Treatment of breakthrough and refractory chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:595894.

- Langley-DeGroot M, Ma JD, Hirst J, Roeland EJ. Olanzapine in the treatment of refractory nausea and vomiting: a case report and review of the literature. . 2015;29:148-152.

- Hesketh PJ, Kris MG, Basch E, et al. Antiemetics: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:3240-3261.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines): Antiemesis. Version 1.2021. December 23, 2020. www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/antiemesis.pdf. Accessed January 14, 2021.

- Rojas C, Thomas AG, Alt J, et al. Palonosetron triggers 5-HT3 receptor internalization and causes prolonged inhibition of receptor function. Eur J Pharmacol. 2010;626:193-199.

- Navari RM, Nagy CK, Le-Rademacher J, Loprinzi CL. Olanzapine versus fosaprepitant for the prevention of concurrent chemotherapy radiotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. J Community Support Oncol. 2016;14:141-147.

- Tan L, Liu J, Liu X, et al. Clinical research of olanzapine for prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2009;28:131.

- Navari RM, Qin R, Ruddy KJ, et al. Olanzapine for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:134-142.

- Nakagaki M, Barras M, Curley C, et al. A randomized trial of olanzapine versus palonosetron versus infused ondansetron for the treatment of breakthrough chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25:607-613.

- Clemmons AB, Orr J, Andrick B, et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled, phase III trial of fosaprepitant, ondansetron, dexamethasone (FOND) versus FOND plus olanzapine (FOND-O) for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in patients with hematologic malignancies receiving highly emetogenic chemotherapy and hematopoietic cell transplantation regimens: the FOND-O trial. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2018;24:2065-2071.

- Roila F, Molassiotis A, Herrstedt J, et al; for the participants of the MASCC/ESMO Consensus Conference Copenhagen 2015. 2016 MASCC and ESMO guideline update for the prevention of chemotherapy- and radiotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting and of nausea and vomiting in advanced cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(suppl 5):v119-v133.

- Yanai T, Iwasa S, Hashimoto H, et al. A double-blind randomized phase II dose-finding study of olanzapine 10 mg or 5 mg for the prophylaxis of emesis induced by highly emetogenic cisplatin-based chemotherapy. Int J Clin Oncol. 2018;23:382-388.

- Trifilio S, Welles C, Seeger K, et al. Olanzapine reduces chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting compared with aprepitant in myeloma patients receiving high-dose melphalan before stem cell transplantation: a retrospective study. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2017;17:584-589.

- Otero Varela L, Wiebe N, Niven DJ, et al. Evaluation of interventions to improve electronic health record documentation within the inpatient setting: a protocol for a systematic review. Syst Rev. 2019;8:54.

- Lorenzetti DL, Quan H, Lucyk K, et al. Strategies for improving physician documentation in the emergency department: a systematic review. BMC Emerg Med. 2018;18:36.

- Hamade N. Improving the Use of Electronic Medical Records in Primary Health Care: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Master’s thesis. University of Western Ontario; 2017. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=6108&context=etd. Accessed October 1, 2020.

- Fosaprepitant. Lexi-Drugs. Lexicomp. Riverwoods, IL: Wolters Kluwer. http://online.lexi.com. Accessed July 5, 2018. [Requires subscription to access.]

- Olanzapine. Lexi-Drugs. Lexicomp. Riverwoods, IL: Wolters Kluwer. http://online.lexi.com. Accessed July 5, 2018. [Requires subscription to access.]