Background: Oral chemotherapy has an ever-increasing role in the treatment of patients with cancer, but high cost increases the risk for primary nonadherence or “nonfulfillment.” Non-fulfillment is defined as failure to obtain a prescribed medication. Proven methods to decrease nonfulfillment rates for oral chemotherapy are lacking in the literature.

Objective: This article describes how our pharmacist-managed oral chemotherapy program (OCP) has impacted nonfulfillment rates by addressing barriers to obtaining the medication, especially medication lack of affordability.

Methods: This study evaluated the percentage of patients who never filled their medications (ie, nonfulfillment) and explored the reasons for lack of initiation of treatment in patients presented to the OCP at St Luke’s Mountain States Tumor Institute (MSTI) between August 2009 and October 2011. Every patient presenting to the program was evaluated for nonfulfillment and for potential reasons for lack of initiation of treatment. In addition, every patient who received financial assistance or a free drug was identified, and the total dollar amount that was saved was compiled. For this evaluation, the total amount of free drugs that was obtained was calculated for each patient by multiplying the average wholesale price of the medication acquired by the average number of cycles the medication is continued in our patient population.

Results: Between August 2009 (the date when the program was initiated) and October 2011, a total of 702 patients were served by MSTI’s OCP. The overall nonfulfillment rate for that period was 9%, and the primary reason for nonfulfillment was patient or physician choice for an alternate therapy. Only 1% of patients overall were unable to obtain the medication because of financial reasons.

Conclusion: Successful collaboration with patient financial advocates has allowed our pharmacist- managed OCP to reach low medication nonfulfillment rates. Maintaining and processing prescriptions within the health system (ie, MSTI) allowed controllable factors for nonfulfillment (ie, cost and loss to follow-up) to be kept at rates lower than those previously seen in other studies. This study did not address mail-order or closed-door pharmacies.

Oral chemotherapy has an ever-increasing role in the treatment of patients with cancer. The number of oral agents available to treat cancer has more than doubled in the past 15 years, and up to 35% of the agents in development are likely to be oral formulations.1 Nonfulfillment, or primary nonadherence, is defined as failure to obtain a medication that has been prescribed.2

The causes of nonfulfillment are numerous, and they are not well described in the literature. Important factors influencing nonfulfillment include patient-perceived concerns about medications, lack of perceived need for medications, and medication affordability issues.3 Nonfulfillment rates have been shown to increase as medication costs increase, especially as it relates to direct patient costs.2,3 Based on average wholesale price (AWP), oral chemotherapy prescriptions can cost from a few hundred dollars per chemotherapy cycle to more than $10,000 per cycle. Therefore, based on cost alone, these medications are at high risk for nonfulfillment. To combat this risk, the financial barriers to patients obtaining these medications need to be addressed.

Nonfulfillment rates vary greatly in the literature. A recent systemic analysis reported an overall mean nonfulfillment rate of 16.4% based on all the studies reviewed.3 Another study focusing on electronic prescribing reported a 24% nonfulfillment rate that varied by class of medication, formulary status, and other factors (oncology medications were not included as a class in this study).4 In a third study, which specifically focused on oral chemotherapy prescriptions, the nonfulfillment rate reported was 10%.5

This present article describes how a pharmacistmanaged oral chemotherapy program (OCP) at one institution has positively affected nonfulfillment rates by addressing barriers to obtaining the prescribed medication, especially lack of medication affordability. This article does not address mail-order or closeddoor pharmacies; this was not included in the current evaluation.

Methods

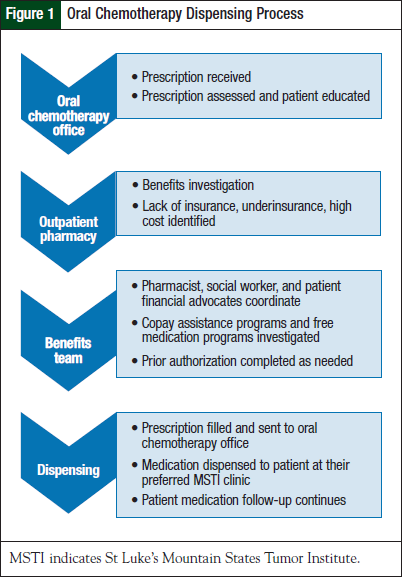

St Luke’s Mountain States Tumor Institute (MSTI) is a National Cancer Institute Community Cancer Center Program with 5 sites that serve a broad geographic area, including southern Idaho, eastern Oregon, and northern Nevada. Prescriptions for oral chemotherapy from any of MSTI’s providers go through a dispensing process as described in Figure 1.

The first step in the process is that the prescriptions are sent directly to the oral chemotherapy office. After a pharmacist conducts a clinical evaluation, the prescription is sent to the outpatient pharmacy for a benefits investigation. A multidisciplinary team, which includes pharmacists, patient financial advocates, and social workers, addresses any potential financial barriers to obtaining the medication. Patient assistance programs are utilized to provide financial aid for uninsured and underinsured patients.

Every patient referred to the OCP is tracked from receipt of the first prescription through termination of the treatment. For this study, the nonfulfillment rate (ie, the number of prescriptions that had been sent to the oral chemotherapy office but never dispensed to the patient) was assessed. These abandoned prescriptions were then classified according to the following reasons for nonfulfillment:

- Inability to obtain the medication, including insurmountable financial issues

- Patient selection of alternate therapy

- Prescriber selection of alternate therapy

- Patient declination of treatment or treatment at a different facility

- Patient complications or death before initiation of treatment.

Once a patient obtains a free drug, the financial advocates follow such a patient and pharmacists are then available for consultation when needed. For this evaluation, the total amount of a free drug that was obtained was calculated for each patient, by multiplying the AWP of the medication acquired by the average number of chemotherapy cycles the medication was continued in our patient population.

Results

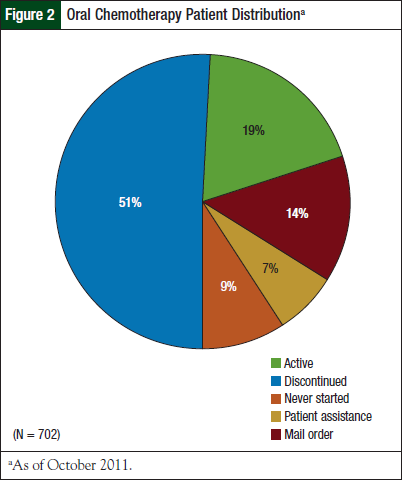

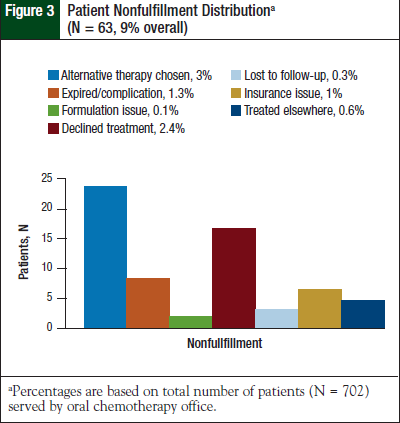

A total of 702 patients have been served by the MSTI OCP from its initiation in August 2009 through October 2011 (Figure 2). During this period, the patient nonfulfillment rate was 9% (N = 63). Of the total number of patients served by the MSTI OCP, only 1% (N = 7) of nonfulfillment was attributable to the inability to obtain the medication or to a medication affordability issue. All other reasons contributing to the nonfulfillment rate are listed in Figure 3.

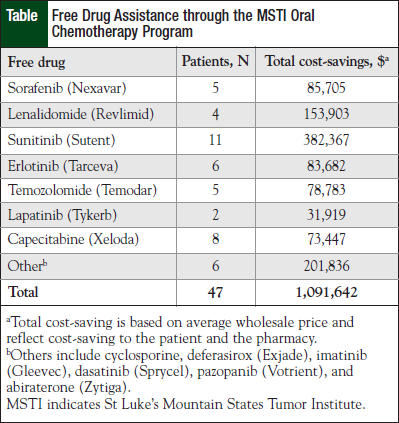

As of October 2011, the MSTI OCP has obtained more than $1 million of free drug assistance (Table) and more than $250,000 of copayment assistance for our patients.

Discussion

The MSTI OCP was described in detail in a previous article published in this journal.6 The goal of the present article is to analyze the impact of this program on medication nonfulfillment.

As the literature consistently reports, the most significant barrier to filling an oral chemotherapy prescription is the patient medication cost. Our patients’ medication affordability issues were attributed to low income, insurance denials, high cost-sharing (copay) insurance, and ineligibility for patient financial or free drug assistance.

At MSTI, patient financial advocates are utilized to help obtain free drug or copay assistance through available patient assistance programs. The Association of Community Cancer Centers and the Oncology Nursing Society have reimbursement resources that patient financial advocates at MSTI use to identify re - imbursement/assistance resources.7,8 High-priced medications and brand-name medications are more likely to have patient medication assistance programs available. Our patient financial advocates have reported that it is easier to obtain patient assistance for medications that are frequently prescribed, for medications prescribed within their US Food and Drug Administration–approved indication, for patients whose income is low or who lack insurance, and for medications that have user-friendly patient assistance programs.

Gadkari and McHorney identified important barriers that contribute to increased nonfulfillment rates, as noted earlier, including patient concerns about medications, patients being unsure of the need for medications, and medication affordability issues.3

At MSTI, patients’ concerns about oral chemotherapy are addressed up front and as therapy progresses by a multidisciplinary healthcare team, including physicians, nurses, and pharmacists. Patients are provided with education on oral chemotherapy for its benefits and for the potential risks to ensure that patients can make an informed medication treatment decision.

Frequent physician follow-up, along with pharmacist initial fill and refill medication counseling, allow for emphasizing the importance of oral chemotherapy medications to MSTI’s patients. Improved communication between the healthcare team and the patient helps to decrease nonfulfillment rates for oral chemotherapy medications.

At MSTI, our evaluation showed other major reasons for nonfulfillment of oral chemotherapy medications, including:

- Choosing an alternative therapy

- The patient declined treatment

- The patient had complications or died before the initiation of treatment.

Alternative therapy was most often chosen based on imaging and pathology results. Physicians send the OCP a “prior authorization only” prescription so the pharmacist can assess prescription insurance coverage, while the imaging and pathology results are pending.

In addition, the choice may be made by either the patient or the physician to decline treatment for advanced cancers when the risks outweigh the benefits. Alternatively, the patient may choose comfort care or hospice. In our evaluation, minor reasons for nonfulfillment were medication formulation issues, treatment at another facility, and loss to follow-up. The minor reasons contributing to nonfulfillment were only observed in <1% of the total patients studied.

The literature reveals little regarding additional methods to decrease nonfulfillment. Several articles offer recommendations for increasing adherence to oral chemotherapy medications,9,10 but they do not address primary nonadherence. Potential avenues for further improvement of primary nonadherence include increased utilization of resources to decrease patient cost for these medications, and increased patient education to address concerns about medications and to emphasize the need for medication adherence.

Conclusions

With our current established prescription processes in place, the MSTI OCP has been able to ensure proper prescription reimbursement. As a result, <1% of the total medication costs have been written off. Successful collaboration with the patient financial advocates has allowed the pharmacist-managed OCP to reach low medication nonfulfillment rates. Maintaining prescription processing within the health system allowed controllable factors for nonfulfillment (ie, cost and loss to follow-up) to be kept at rates lower than those seen in previous studies.

Author Disclosure Statement

Dr Drenker and Dr Sondag reported no conflicts of interest. Dr Mancini is on the Speaker’s Bureau for Millennium Pharmaceuticals.

References

- DeCardenas R, Helfrich J. Oral therapies and safety issues for oncology practices. Oncol Issues. 2010;March/April:40-42.

- Gellad WF, Grenard J, McGlynn EA. A review of barriers to medication adherence: a framework for driving policy options. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation; 2009. www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/technical_reports/2009/RAND_TR765.pdf. Accessed June 14, 2012.

- Gadkari AS, McHorney CA. Medication nonfulfillment rates and reasons: narrative systematic review. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010;26:683-705.

- Fischer MA, Choudhry NK, Brill G, et al. Trouble getting started: predictors of primary medication nonadherence. Am J Med. 2011;124:1081.e9-1081.e22.

- Streeter SB, Schwartzberg L, Husain N, Johnsrud M. Patient and plan characteristics affecting abandonment of oral oncolytic prescriptions. J Oncol Pract. 2011;7(3 suppl):46s-51s.

- Mancini R, Kaster L, Vu B, et al. Implementation of a pharmacist-managed interdisciplinary oral chemotherapy program in a community cancer center. J Hematol Oncol Pharm. 2011;1:23-30.

- Association of Community Cancer Centers. Reimbursement and patient assistance programs: a guide for community cancer centers. Oncology Issues. 2011;January/February:S1-S58.

- Moore S, Brandt ML. Adherence to Oral Therapies for Cancer: Helping Your Patients Stay on Course Toolkit. 2010. www.ons.org/ClinicalResources/OralTherapies/media/ons/docs/clinical/AdherenceToolkit/oraladherencetoolkitprint. pdf. Accessed June 14, 2012.

- Partridge AH, Avorn J, Wang PS, Winder EP. Adherence to therapy with oral antineoplastic agents. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:652-661.

- Schneider SM, Hess K, Gosselin T. Interventions to promote adherence with oral agents. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2011;27:133-141.