Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) is a family of lymphoid malignancies with more than 50 recognized subtypes that arise from lymphocytes.1 Anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies, including rituximab, obinutuzumab, and ofatumumab, were originally developed and approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of B-cell proliferative disorders, including NHL.2 These agents bind to the surface CD20 antigen that is widely expressed in malignant and nonmalignant B lymphocytes and leads to the destruction and eventual depletion of B-cells.3

Patients who had been infected with the hepatitis B virus (HBV) and are receiving immunosuppressive or cytotoxic therapies are at risk for HBV reactivation.4,5 As a result of reports of severe HBV infection flares in patients receiving anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies, the FDA issued black box warnings for ofatumumab and for rituximab in September 2013.6

The rate of HBV reactivation in patients who were at risk for reactivation after receiving anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies is not well-defined, as is evident by a meta-analysis showing a risk of 20% to 80% for reactivation in patients with positive hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg).5 A 2015 meta-analysis showed a rate of 6.3% of HBV reactivation in patients with lymphoma and negative HBsAg who received rituximab.7 The American Gastroenterological Association ranks patients receiving anti-CD20 antibodies as the highest-risk group for HBV reactivation, with high confidence, along with anthracycline derivatives, such as doxorubicin.8

Evidence-based monitoring strategies geared toward patients with lymphoma who are at risk for HBV reactivation are necessary to prevent complications. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) provides recommendations to prevent HBV reactivation during and after cancer treatment.9,10

Based on these recommendations, all patients should be screened for HBsAg and hepatitis B core antibody (HBcAb) before initiating anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies. If positive for HBsAg and/or HBcAb, patients should be prescribed antiviral prophylaxis, which should be continued throughout anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody therapy and for up to 12 months after the completion of treatment. Screening for hepatitis B surface antibody (HBsAb) may also be performed to test for immunity. For monitoring, the NCCN recommends to obtain HBV viral load, by polymerase chain reaction, before initiating anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies, then monthly during therapy, and every 3 months after the completion of therapy, for up to 12 months.9,10

Our institution, the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, implemented a best practice advisory (BPA) alert within the electronic health record (EHR) system to alert prescribers if a patient had abnormal HBV screening results when signing any medication order that requires dual signatures, including anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies. This quality improvement study aimed to determine the rate of appropriate HBV monitoring and treatment, as defined by the NCCN guidelines,9,10 in patients with lymphoma receiving anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies, and to assess if the implementation of the BPA intervention resulted in at least a 20% increase in appropriate HBV monitoring and treatment.

Methods

In this single-center, retrospective cohort study we compared the rates of appropriate HBV monitoring and treatment in patients with lymphoma and with a history of HBV infection receiving anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies before and after an institutional BPA was implemented in the EHR system of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center on February 12, 2020. The patients’ data were collected until November 1, 2020, and the BPA is currently active in the EHR system.

This quality improvement study was approved by, and conducted in compliance with, our institution’s Quality Improvement Assurance Board requirements. Patients were identified using a drug administration report that was generated by the EHR. Patients aged ≥18 years who received any anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies therapy (rituximab, obinutuzumab, or ofatumumab, including biosimilars) and had abnormal HBV testing panel results, defined as HBsAg positive and/or HBcAb positive, were included in the report. These patients were then further filtered to include only the patients with lymphoma.

The patients were divided into 2 retrospective cohorts based on the date that they started a new treatment regimen before or after the BPA was implemented. The pre-BPA implementation cohort included patients who started a new treatment regimen between January 1, 2016, and February 11, 2020, and the post-BPA implementation cohort included patients who initiated a new treatment regimen and were flagged in the EHR by the BPA between February 12, 2020, and November 1, 2020.

All patients who were receiving anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody therapy for an indication other than lymphoma were excluded from the study.

Best Practice Advisory

A BPA is a clinical decision support tool in the EHR system that is used to promote or require certain clinical practices; the BPA essentially exists as reminder tools that are strategically placed in the EHR system and are aimed at the respective end users (eg, providers, pharmacists). The BPA was implemented at our institution to flag providers who were signing any prescription orders requiring 2 signatures (eg, chemotherapy) for abnormal HBV panel results.

The provider must select 1 of 4 options from the BPA, which include “placed a specialist consult,” “patient already had therapy,” “not the appropriate provider,” or “see comments.” The BPA is triggered to fire on the EHR every 6 months per a chemotherapy treatment plan.

Study Variables

The data collected for all patients from the EHR system included the lymphoma diagnosis, the anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody (with or without chemotherapy regimen), start date and end date (if applicable) of lymphoma treatment, date and results of the initial HBV testing panel, HIV status, antiviral drug therapy, antiviral agent and dose, changes in HBV monitoring or therapy, whether the corresponding viral load values were monitored after the start of antiviral therapy, and the positive viral loads during monitoring.

In addition, the data collected for all patients in the postimplementation cohort included the date of the BPA (which was triggered in the EHR system), the option selected on the BPA, and whether a consultation was placed.

The HBV test results were obtained almost exclusively from in-house microbiology testing and, for a few patients, from outside medical records.

The study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools.11 Descriptive statistics were used to assess the primary outcome in each cohort.

The primary outcome was the rate of patients at risk for HBV reactivation who were appropriately monitored and treated. Appropriate monitoring and treatment were defined to reflect the NCCN guidelines9,10 as (1) any patient with abnormal HBV test results who started and continued antiviral prophylaxis throughout the lymphoma therapy (ie, anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies) and for up to 12 months after the completion of the therapy, and (2) the viral load obtained monthly while receiving lymphoma therapy and every 3 months after the completion of lymphoma therapy for up to 12 months.

Several patients in both cohorts, although mostly in the postimplementation cohort, were still receiving anti-CD20 therapy at the time of data cutoff; therefore, the analysis was considered to be intention to treat, because an evaluation of post–anti-CD20 therapy monitoring and treatment could not be performed in these patients. Patients with appropriate monitoring and treatment during the anti-CD20 therapy who had no post-therapy data were considered to be positive for the primary outcome at the time of data cutoff.

Results

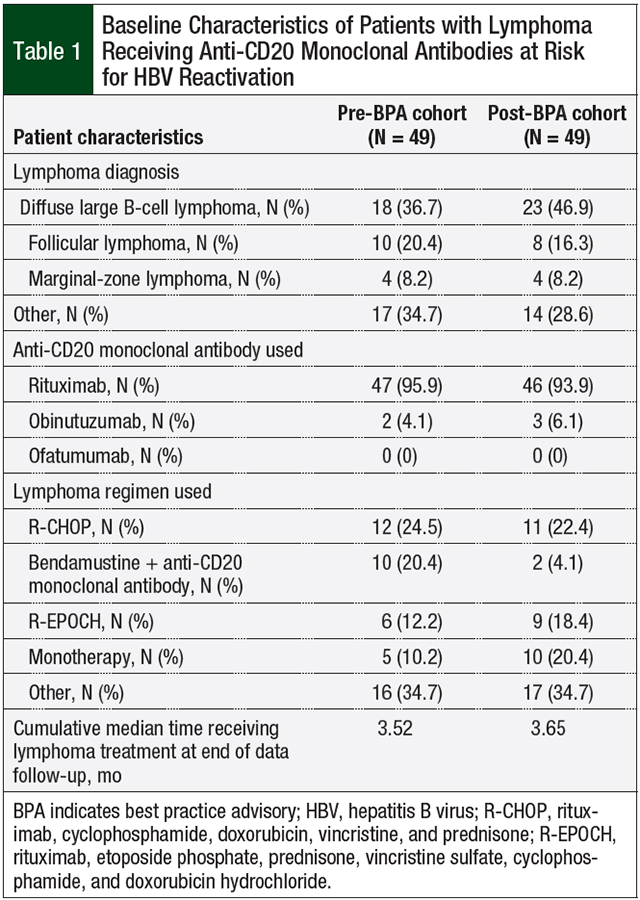

A total of 98 individual patients were included in this study, with 49 patients in each of the 2 respective cohorts (ie, preimplementation and postimplementation). The baseline patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. The most common lymphoma diagnosis was diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in both groups, followed by follicular lymphoma. Rituximab was administered to more than 90% of patients in both cohorts.

The most common lymphoma regimen in both cohorts was R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone). The second most common lymphoma regimen in the preimplementation cohort was bendamustine plus either rituximab or obinutuzumab; in the postimplementation cohort monotherapy with an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody was the most common treatment (Table 1).

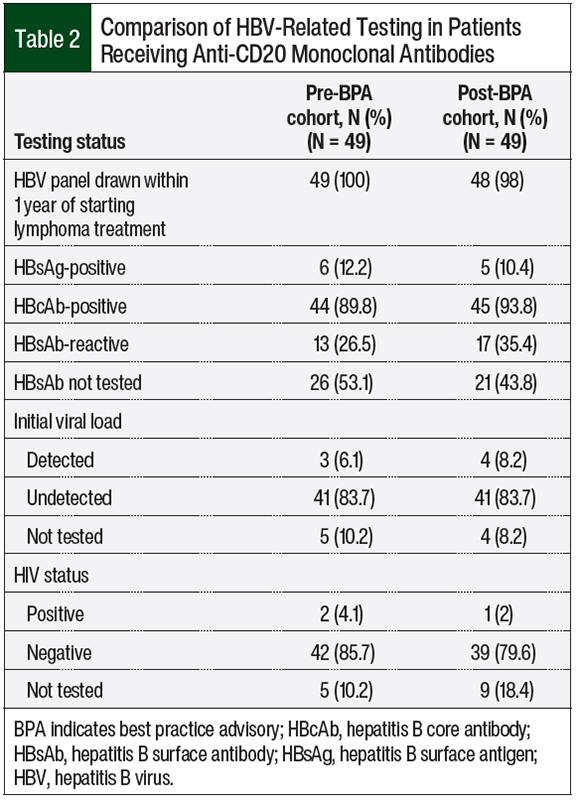

Comparisons of the various HBV-related testing are shown in Table 2. In the preimplementation cohort, 12.2% of patients tested positive for HBsAg and 89.8% were positive for HBcAb. In the postimplementation cohort, 10.4% of patients tested positive for HBsAg and 93.8% were positive for HBcAb. Only 52% of patients were tested for HBsAb, because this laboratory test is not a component of the infectious disease panel order set at our institution.

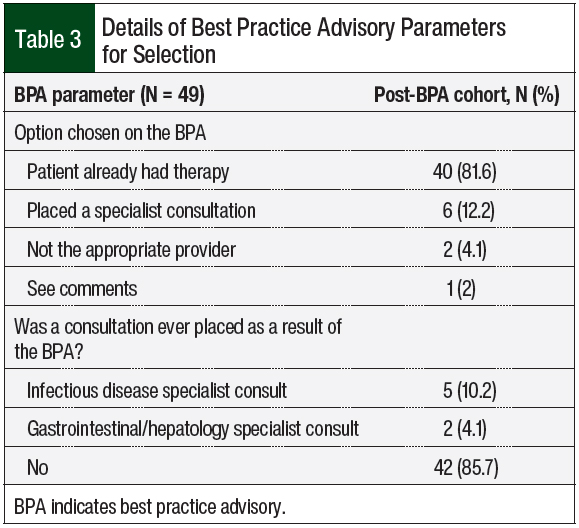

The most common BPA option selected was “patient already had therapy,” with 81.6% of users choosing this option, followed by 12.2% choosing the option labeled “placed a specialist consult.” An infectious disease or gastrointestinal/hepatology consultation was selected for 10.2% and 4.1% of patients, respectively, directly from the BPA tool (Table 3).

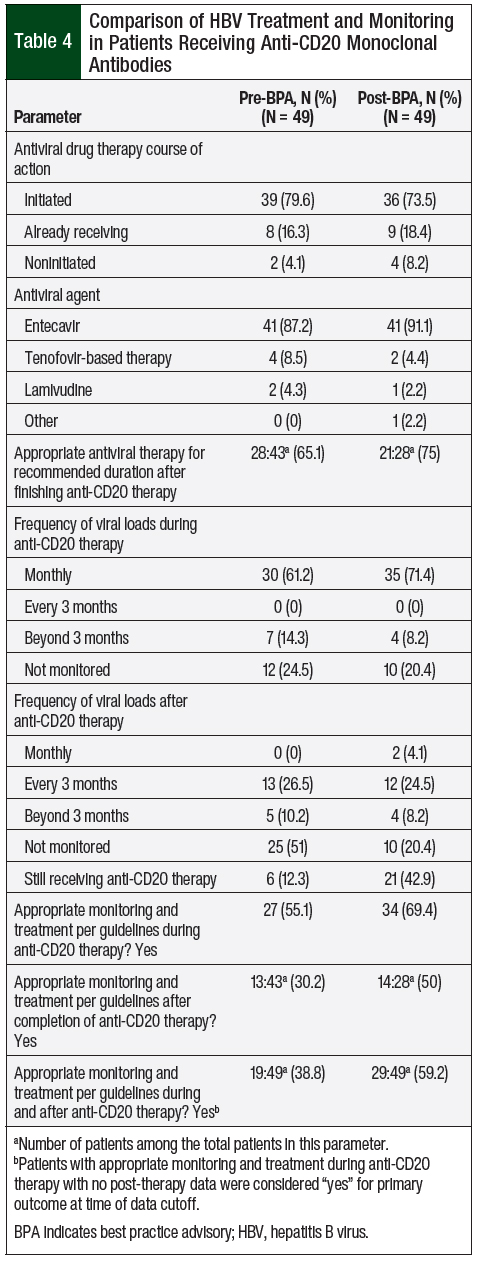

In the preimplementation cohort, 95.9% of patients either started or continued using the previous antiviral therapy compared with 91.9% of patients in the postimplementation cohort (Table 4). Entecavir was the predominant agent in both cohorts, with 87.2% and 91.1% of the patients receiving antiviral therapy with entecavir in the pre- and postimplementation cohorts, respectively. In all, 43 patients in the preimplementation cohort and 28 patients in the postimplementation cohort could be evaluated for appropriate antiviral treatment duration after the completion of therapy.

Of the 49 patients in the preimplementation cohort, 6 were still receiving anti-CD20 therapy at the time of the data analysis, so we could not assess if they had appropriate monitoring and treatment after receiving anti-CD20 therapy. This incompletion of therapy was a more pronounced issue in the postimplementation cohort, of which 21 patients were still receiving anti-CD20 therapy (Table 4).

Of the 43 patients in the preimplementation cohort, 28 (65.1%) were receiving the appropriate antiviral therapy for the recommended duration after finishing anti-CD20 therapy compared with 21 (75%) of the 28 patients in the postimplementation cohort. The corresponding viral loads were monitored monthly during therapy in 61.2% of patients in the preimplementation cohort and in 71.4% of the patients in the postimplementation cohort. After the completion of anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody therapy, 51% of patients in the preimplementation group were not monitored for viral load compared with 20.4% of patients in the postimplementation cohort (Table 4).

While receiving anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody therapy, 55.1% of patients were appropriately monitored and treated in the preimplementation cohort compared with 69.4% in the postimplementation cohort (Table 4). The appropriate monitoring and treatment were determined by the NCCN’s recommendations for viral load monitoring (ie, frequency) and antiviral treatment and prophylaxis (ie, drug and duration).9,10 While receiving anti-CD20 therapy, at-risk patients should be tested for a viral load monthly and should be receiving the recommended antiviral drugs throughout treatment.9,10

In our study, if the patients met both criteria, they were considered to be appropriately monitored and treated. If they did not meet either of the 2 criteria, they were deemed to be inappropriately monitored and treated, because each of the 2 criteria is essential.

Approximately 30% of the patients who finished anti-CD20 therapy were monitored and treated appropriately in the preimplementation cohort compared with 50% of the patients in the postimplementation cohort. Combining these 2 outcomes, the composite primary end point of the rate of patients who were appropriately monitored and treated for HBV reactivation during and after receiving anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies therapy was 38.8% in the preimplementation cohort (Table 4). This rate increased by 20.4%—to 59.2%—in the postimplementation cohort.

Discussion

The majority of patients with B-cell lymphomas receive anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies, and providers must be cognizant of the risk for HBV reactivation with these agents, because they carry the highest risk for reactivation of all of the cytotoxic or immunosuppressive drugs.8 Standards of practices should be continually updated with the most recent evidence-based recommendations for HBV prophylaxis and monitoring.

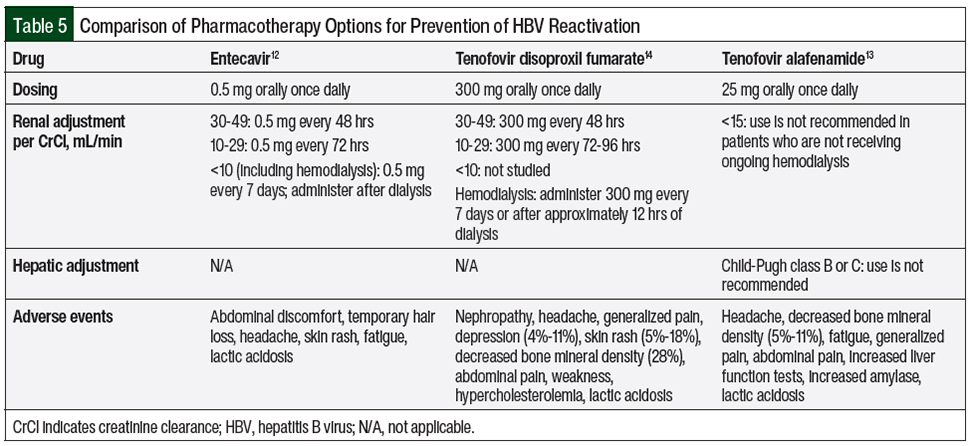

The preferred agents for HBV prophylaxis by the NCCN guidelines are entecavir and tenofovir monotherapy.9,10 Table 5 summarizes the key clinical information regarding these agents.12-14 Tenofovir is commercially available in 2 formulations, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate and tenofovir alafenamide, with no recommended preference (to our knowledge) for one versus the other.13,14 In addition, it is important to remember that tenofovir may be included in HIV treatment combinations, such as the triplet regimen of bictegravir, emtricitabine, and tenofovir alafenamide, which can double as an HBV-directed therapy.15

Lamivudine is no longer recommended by the NCCN, because of its high (80%) resistance rate after 5 years of treatment.9,10,16 The potential for antiviral resistance is lower with entecavir than with lamivudine and is absent with tenofovir.9,10

Entecavir and tenofovir are generally well-tolerated, but patients receiving either agent should be monitored for lactic acidosis and for severe hepatomegaly with steatosis, whereas those receiving tenofovir should also be monitored for nephrotoxicity.12-14 Entecavir and tenofovir require dose adjustment for renal impairment.12-14

Prescription drug costs and insurance preauthorization may be potential barriers to optimal management; however, there are several avenues, including patient assistance programs, online pharmacies, and discount prescription cards, that may aid with drug procurement.

More than 95% of patients in both cohorts were started with entecavir- or tenofovir-based therapy. The current NCCN guidelines recommend antiviral prophylaxis to be continued throughout anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody therapy and for up to 12 months after the completion of treatment.9,10 In our study, only 65.1% of patients in the preimplementation cohort and 75% of patients in the postimplementation cohort (at the time of data collection cutoff) were receiving antiviral therapy for the recommended duration.

The HBV viral load should be monitored monthly during therapy, and every 3 months after the completion of therapy, for up to 12 months. In the preimplementation cohort, 61.2% of patients had viral loads monitored monthly. However, after finishing therapy, 26.5% of patients had viral loads drawn every 3 months, 51% were not monitored for viral load, and 12.3% were still receiving anti-CD20 therapy at the time of data collection cutoff (ie, patients who had passed away while receiving therapy).

In the postimplementation cohort, 71.4% of patients were monitored monthly during therapy, and 50% of the patients were appropriately monitored after the completion of therapy. Approximately 20% of patients in the postimplementation cohort had no viral load monitoring after therapy; however, this percentage may be higher if given a longer follow-up period. In addition, 42.9% of patients in the postimplementation cohort were still receiving anti-CD20 therapy at the time of data collection cessation.

The primary outcome was a composite that combined appropriate monitoring (viral loads) and treatment (antiviral therapy) during and after receiving anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies therapy. The BPA tool was an initial attempt at implementing a system-wide intervention within the EHR system to prompt providers of the necessary steps to prevent HBV.

Meeting the predetermined 20% improvement goal of our study suggests that the implementation of this BPA was meaningful, but there are still opportunities for improvement, because more than 40% of this select patient population were not appropriately monitored for HBV reactivation. Thus, additional interventions are necessary.

To address this shortcoming of >40% of patients not being monitored for HBV reactivation, 2 interventions are currently in process. First, a tip sheet was developed that summarizes the current NCCN guideline recommendations and serves as a visual aid that providers can use during the treatment planning process. This tip sheet will be distributed to physicians and advanced practice practitioners who manage patients with lymphoma or myeloma, along with an in-service education session to discuss these recommendations. The maintenance of this tip sheet will also be necessary, because guideline recommendations are continually updated.

In addition, new parameters were considered to streamline the provider experience and to adjust the options that are within the BPA. The current BPA serves as an acknowledgment that the patient has abnormal HBV results and an action (such as starting anti-CD20 therapy) has to be taken rather than facilitating the ordering of medications or laboratory testing.

The proposed changes are to add statements for guideline recommendations, to link to an HBV management algorithm, and to add options to prescribe or order medications and laboratory tests. However, many factors and stakeholders would need to be involved for these types of large-scale alterations.

Limitations

A primary study limitation is the retrospective nature of the study. In addition, the postimplementation cohort only had 10 months of data at the end of the data collection, and more than 40% of patients were still receiving treatment for lymphoma at the time; thus, longer follow-up would have been beneficial.

Other limitations stem from the specific interventions that we can make with the BPA in the EHR system, and, in particular, the technical limitations of altering the BPA. The proposed interventions were deemed unfeasible because of technical limitations, despite the agreement that they would be beneficial.

Finally, our institution is a referral site, where many patients are not local and may transition their cancer care after receiving their initial treatment, which did not allow for more frequent follow-up and laboratory monitoring.

Conclusion

When evaluated 10 months after its implementation, this BPA intervention resulted in a 20.4% increase in appropriate HBV monitoring and treatment in patients with lymphoma, meeting the study’s objective of 20% improvement. Further follow-up of the postimplementation cohort could potentially confirm the efficacy of this current BPA. Additional interventions are needed, because more than 40% of the patients identified were not being managed per current guideline recommendations. These interventions could be the focus of future quality improvement initiatives in search of the solutions to this significant patient safety concern.

Acknowledgments

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the University of Texas and its affiliated academic healthcare centers.

Author Disclosure Statement

Dr Sinoimeri, Dr Do, and Dr Chen have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- Leukemia & Lymphoma Society. Non-Hodgkin lymphoma. www.lls.org/lymphoma/non-hodgkin-lymphoma. Accessed February 24, 2022.

- Huynh Du F, Mills EA, Mao-Draayer Y. Next-generation anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies in autoimmune disease treatment. Auto Immun Highlights. 2017;8:12. doi: 10.1007/s13317-017-0100-y.

- Plosker GL, Figgitt DP. Rituximab: a review of its use in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Drugs. 2003;63:803-843.

- Mitka M. FDA: increased HBV reactivation risk with ofatumumab or rituximab. JAMA. 2013;310:1664.

- Evens AM, Jovanovic BD, Su YC, et al. Rituximab-associated hepatitis B virus (HBV) reactivation in lymphoproliferative diseases: meta-analysis and examination of FDA safety reports. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:1170-1180.

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA drug safety communication: boxed warning and new recommendations to decrease risk of hepatitis B reactivation with the immune-suppressing and anti-cancer drugs Arzerra (ofatumumab) and Rituxan (rituximab). September 25, 2013. www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-drug-safety-communication-boxed-warning-and-new-recommendations-decrease-risk-hepatitis-b. Accessed February 24, 2022.

- Mozessohn L, Chan KKW, Feld JJ, Hicks LK. Hepatitis B reactivation in HBsAg-negative/HBcAb-positive patients receiving rituximab for lymphoma: a meta-analysis. J Viral Hepat. 2015;22:842-849.

- Perrillo RP, Gish R, Falck-Ytter YT. American Gastroenterological Association Institute technical review on prevention and treatment of hepatitis B virus reactivation during immunosuppressive drug therapy. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:221-244.e3.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines): Prevention and Treatment of Cancer-Related Infections. Version 1.2021. July 2, 2021. www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/infections.pdf. Accessed February 28, 2022.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines): B-Cell Lymphomas. Version 5.2021. September 22, 2021. www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/b-cell.pdf. Accessed February 28, 2022.

- Harris PA Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377-381.

- Baraclude (entecavir) tablets, for oral use/oral solution [prescribing information]. Bristol-Myers Squibb; November 2019. https://packageinserts.bms.com/pi/pi_baraclude.pdf. Accessed February 28, 2022.

- Vemlidy (tenofovir alafenamide) tablets, for oral use [prescribing information]. Gilead Sciences; September 2021. www.gilead.com/~/media/files/pdfs/medicines/liver-disease/vemlidy/vemlidy_pi.pdf?la=en. Accessed February 28, 2022.

- Viread (tenofovir disoproxil fumarate) tablets/powder, for oral use [prescribing information]. Gilead Sciences; April 2019. www.gilead.com/~/media/Files/pdfs/medicines/liver-disease/viread/viread_pi.pdf. Accessed February 28, 2022.

- Biktarvy (bictegravir, emtricitabine, and tenofovir alafenamide) tablets, for oral use [prescribing information]. Gilead Sciences; October 2021. www.gilead.com/~/media/files/pdfs/medicines/hiv/biktarvy/biktarvy_pi.pdf. Accessed February 28, 2022.

- Gish RG. Hepatitis B treatment: current best practices, avoiding resistance. Cleve Clin J Med. 2009;76(suppl 3):S14-S19.