Daratumumab is a first-in-class immunoglobulin G1 kappa human monoclonal antibody directed against CD38, a cell-surface glycoprotein that is highly expressed on multiple myeloma cells.1 By binding to CD38, daratumumab inhibits the growth of CD38-expressing tumor cells by inducing apoptosis

directly through Fc-mediated cross linking, as well as by immune-mediated tumor-cell lysis through complement-dependent cytotoxicity, antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity, and antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis.1

Daratumumab is indicated for the treatment of patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma, as well as for patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma.1,2 In addition, many clinical trials, ongoing and some that have been completed that have investigated the use of daratumumab in various treatment combinations.3,4

Overall, daratumumab is well-tolerated; however, treatment with daratumumab is associated with a high incidence of infusion reactions.1 In clinical trials, 37% of patients had an infusion-related reaction during the first infusion of daratumumab.1 The risk for infusion-related reactions after receiving treatment with daratumumab is lower with subsequent infusions (2%-6%); in clinical trials, less than 1% of patients had a grade 3 infusion reaction with second or subsequent infusions.1

Because of the risk for infusion-related reactions, the prescribing information for daratumumab recommends administering pre- and postinfusion medications with each infusion.1 In addition, Chari and colleagues examined premedication with montelukast before receiving daratumumab treatment to reduce infusion reactions, which has proved beneficial.5

The approved initial infusion of daratumumab, per the prescribing information, is administered over approximately 7 hours, the second infusion is administered over approximately 4 hours, and all subsequent infusions are administered over approximately 3 hours, which can lead to long treatment days for patients.1,6

Additional studies that examined the feasibility of infusing daratumumab over 90 minutes in patients who have received at least 2 previous doses of daratumumab at standard infusion rates have shown that this accelerated infusion is well-tolerated in patients.6,7

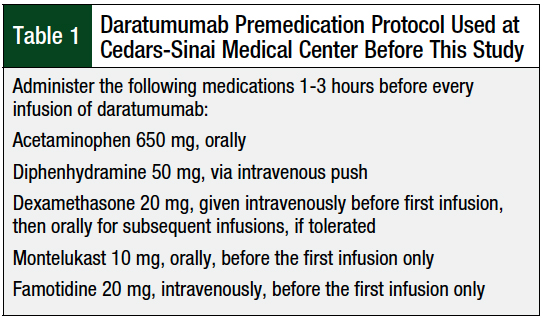

Before our study, the policy at our infusion center at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, CA, was to follow the preinfusion medication recommendations of the prescribing information of daratumumab to prevent infusion reactions (Table 1). This policy included the administration of acetaminophen, a steroid, and an antihistamine before each infusion. In addition, famotidine and montelukast are given before the first infusion of daratumumab (Table 1).

According to this protocol, patients received all premedications, including dexamethasone, in the clinic before any infusion of daratumumab. Per the prescribing information for daratumumab, it is also recommended that postinfusion steroids be considered, as well as bronchodilators for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.1 At Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, however, it is not a common practice to administer steroids or bronchodilators postinfusion.

One of our multiple myeloma providers at our center discontinues preinfusion medications for daratumumab, excluding dexamethasone if it is part of the treatment for multiple myeloma, after the initial 3 to 5 doses, in all patients who previously tolerated the initial daratumumab infusions without adverse reactions. At dose 5 or later, this provider starts to accelerate the infusion rate of daratumumab to 90 minutes (200 mL/hr for

30 minutes, then 450 mL/hr) for patients who tolerate the first 3 to 5 infusions without difficulty instead of the standard titration rate, which can take up to 4 hours.

The goal of this study was to standardize the administration procedure for daratumumab treatment across Cedars-Sinai Medical Center. We compared the rates of infusion-related reactions using the Fischer’s exact test, and the t-test was used to compare the patients’ characteristics.

The primary objective of this study was to compare the incidence of infusion-related reactions after the omission of premedications versus the current standard premedications in patients who receive daratumumab treatment (ie, cohort 1 vs cohort 2). The secondary objective was to analyze the incidence of infusion-related reactions in patients who receive rapid infusion daratumumab (defined as 90 minutes).

Methods

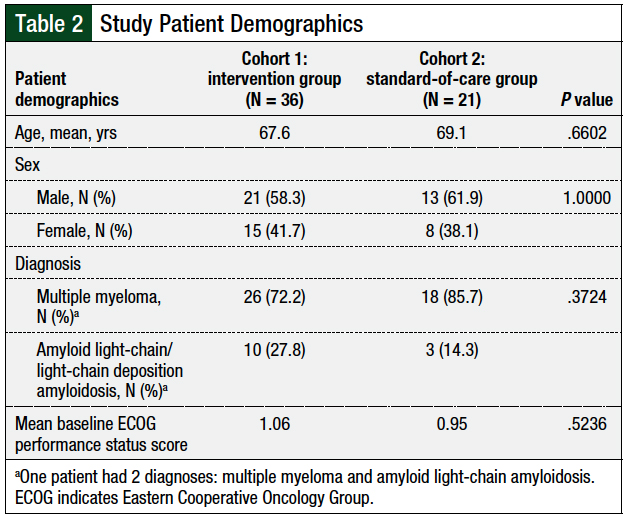

We conducted a retrospective chart review between November 2017 and December 2018 to identify patients with a diagnosis of multiple myeloma, amyloid light-chain amyloidosis, or light-chain deposition disease who completed at least 1 cycle of daratumumab, which was defined as 4 doses, at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center. A total of 57 patients were identified during the study period for inclusion. We divided the patients into 2 cohorts. Cohort 1 included 36 patients who had omitted premedication, per the physician’s judgment, on or after dose 3 of cycle 1. Cohort 2 included 21 patients who received standard premedications, as defined by the prescribing information of daratumumab.1

All the patients in both cohorts received montelukast 10 mg and famotidine 20 mg intravenously before the first infusion of daratumumab. The data we collected include the patient’s diagnosis, age, sex, the premedications given to the patient, the median week that the premedications were stopped, the infusion times, and the presence of any infusion-related reactions (graded per the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events8). Data regarding premedications other than those previously mentioned, such as albuterol, were not collected.

We collected the data by searching for physician or nursing comments regarding the presence or absence of infusion-related reactions, including any time the infusion was stopped or paused (which required further documentation of reason); such documentation is the standard of care at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center.

Our data showed that only 1 physician omitted premedications during the patients’ course of daratumumab treatment, which would have included diphenhydramine and acetaminophen, and dexamethasone if it were a premedication and not a part of the treatment regimen.

This physician initially omitted the premedications at doses 6 to 9; as he became more comfortable that patients were not having infusion reactions, that physician started to eliminate the premedications after doses 3 to 5.

Results

The patients’ demographics were well-balanced between the 2 cohorts (Table 2). After the first infusion of daratumumab with standard premedications (Table 3), 15 (41.7%) infusion-related reactions were reported in cohort 1 (ie, the intervention group) versus 8 (38.1%) reactions in cohort 2 (ie, the standard-of-care group).

In subsequent infusions of daratumumab, only 1 infusion-related reaction was reported in cohort 1, which was headache; this patient was only receiving dexamethasone as part of the treatment regimen and, of note, did not have a history of infusion-related reaction.

In cohort 2, there were 2 infusion-related reactions, which included itching and chills; these 2 patients had received dexamethasone as part of their treatment regimen and acetaminophen and diphenhydramine as premedications. One of these 2 patients who had an infusion-related reaction during a subsequent infusion also had an infusion-related reaction during the first infusion. The difference in infusion-related reactions between the 2 cohorts after the discontinuation of the premedication was not significant (P = .5478; Table 3).

In cohort 1, all 36 patients were able to omit diphenhydramine as a premedication, and 34 patients omitted diphenhydramine and acetaminophen as premedications, all by a median of week 5 (range, 3-6); 1 patient received dexamethasone and acetaminophen, and 1 patient received acetaminophen alone. A total of 6 patients were able to discontinue the premedications entirely, including dexamethasone, by a median of week 5 (range, 3-5). None of these patients had an infusion-related reaction during subsequent infusions of daratumumab. The median time of discontinuation of at least 1 premedication was week 5 (range, 3-9).

The average infusion time was similar between the 2 cohorts during the first dose of daratumumab treatment: 7.3 hours in cohort 1 versus 7.6 hours in cohort 2. A total of 12 patients in cohort 1 had subsequent infusions after dose 5 that lasted more than 90 minutes, which did not result in any infusion-related reactions; of these 12 patients, 1 did not receive any premedications, 10 patients received only dexamethasone, and 1 patient received only acetaminophen. All the patients in cohort 2 received infusions at the rates listed in the prescribing information of daratumumab.1

Discussion

As far as we know, this is the first study to demonstrate that it is safe to omit preinfusion medications gradually before the administration of daratumumab after patients have successfully tolerated the initial 3 to 5 infusions of daratumumab. Only 1 infusion-related reaction was reported after the premedications were discontinued in the intervention group. Moreover, this patient complaint (ie, reaction) was a headache, which could be caused by other factors that are not related to the infusion of daratumumab.

Dexamethasone is given as a premedication, as well as a treatment for multiple myeloma; however, clinicians often adjust the dose of dexamethasone based on patients’ disease burden, as well as their ability to tolerate steroids.9

In cohort 1 of our study, a total of 6 patients stopped dexamethasone as premedication in subsequent infusions, and they were able to tolerate daratumumab treatment without infusion-related reactions. Therefore, if dexamethasone is not used for the treatment of multiple myeloma, it suggests that it could be discontinued as a premedication.

Hamadeh and colleagues demonstrated that treatment with daratumumab can be successfully given at a rapid infusion rate of 90 minutes.7 The results of our study further support the safety of infusing daratumumab at this accelerated rate; a total of 12 patients were able to receive daratumumab treatment safely over 90 minutes. Moreover, diphenhydramine premedication was discontinued in all 12 patients, and acetaminophen premedication was discontinued in 11 patients.

Daratumumab can be used as monotherapy,10,11 as well as in combination with other anti–multiple myeloma agents. The dosing schedule of daratumumab may vary, depending on the combination treatment used; however, treatment with daratumumab is most often given weekly for the first 8 doses, then biweekly for another 8 doses, and every 4 weeks thereafter.1

Therefore, patients come to the clinic frequently and spend a significant amount of time there during each infusion. The prescribing information for daratumumab recommends administering premedications 1 to 3 hours before each infusion,1 which adds even more time for patients to be in the clinic.

By omitting premedications and escalating the infusion rate, we can shorten patients’ time in the infusion area by at least 2 hours and prevent unnecessary side effects from premedications, particularly drowsiness from diphenhydramine, which can interfere with patients’ abilities to drive after treatment.

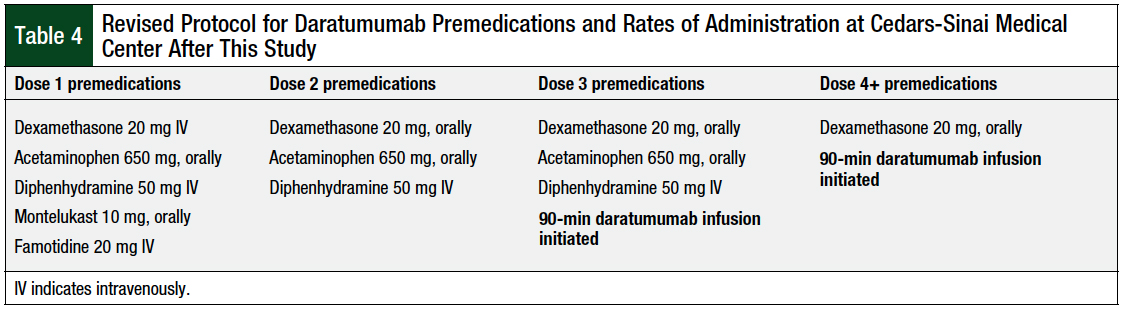

After seeing the results of this study, our institution changed the treatment plans for daratumumab to include a steroid (dexamethasone), acetaminophen, diphenhydramine, montelukast, and famotidine, to be given before the first dose of daratumumab (Table 4).

Before doses 2 and 3 of daratumumab, a steroid, acetaminophen, and diphenhydramine are given. Starting with dose 4, only an oral steroid is administered before the infusion of daratumumab. In addition, the rate of infusion of daratumumab was changed in dose 3 (Table 4). As shown in Table 4, at dose 3 of daratumumab, the rate of infusion has been changed to 90 minutes (200 mL/hr for 30 minutes, then 450 mL/hr).

Limitations

This study has several limitations. The retrospective nature of this study, using data in patients’ charts, is a limitation. Another limitation is the small sample size of the patient population in this study.

Furthermore, the collection of data on infusion-related reactions relied on information in the chart noted by nurses and physicians to determine whether patients tolerated the medication, which could explain the lower rate of infusion-related reactions during the initial infusion versus the rate reported in clinical trials.

In addition, data were not collected regarding delayed infusion reactions that might have occurred after patients left the infusion clinic or on how many lines of therapy patients did not respond to before starting treatment with daratumumab.

Another limitation is that removing premedications and reducing infusion times introduced confounding variables. This is especially true because it is unclear how the provider chose when to omit the premedications.

Conclusion

Our retrospective chart review demonstrates that omitting premedications after patients have tolerated the initial infusions of daratumumab with premedications for at least 3 doses is feasible and does not result in an increase in infusion-related adverse reactions. In addition, as seen in other studies, a shorter infusion time of 90 minutes of daratumumab did not lead to any additional infusion-related reactions. Reducing premedications and the infusion time can decrease medication-related adverse events and reduce the time burden on patients.

Author Disclosure Statement

Dr Preedit and Dr Yudchyts have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- Darzalex (daratumumab) injection, for intravenous use [prescribing information]. Horsham, PA: Janssen Biotech; August 2020.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines): Multiple Myeloma. Version 3.2021. October 19, 2020. www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/myeloma.pdf. Accessed November 20, 2020.

- Nooka AK, Gleason C, Sargeant MO, et al. Managing infusion reactions to new monoclonal antibodies in multiple myeloma: daratumumab and elotuzumab. J Oncol Pract. 2018;14:414-422.

- National Cancer Institute. Clinical trials using daratumumab. www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/clinical-trials/intervention/daratumumab. Accessed August 24, 2019.

- Chari A, Mark TM, Krishnan A, et al. Use of montelukast to reduce infusion reactions in an early access treatment protocol of daratumumab in United States patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. Blood. 2016;128:2142.

- Barr H, Dempsey J, Waller A, et al. Ninety-minute daratumumab infusion is safe in multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2018;32:2495-2518.

- Hamadeh IS, Arnall J, Kachur E, et al. Rapid infusion daratumumab is safe and well tolerated in clinical practice. Blood. 2018;132(suppl 1):2255.

- National Cancer Institute. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE). Version 5.0. November 27, 2017. https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocoldevelopment/electronic_applications/docs/CTCAE_v5_Quick_Reference_8.5x11.pdf. Accessed December 27, 2018.

- Chung CH. Managing premedications and the risk for reactions to infusional monoclonal antibody therapy. Oncologist. 2008;13:725-732.

- Lokhorst HM, Plesner T, Laubach JP, et al. Targeting CD38 with daratumumab monotherapy in multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1207-1219.

- Lonial S, Weiss BM, Usmani SZ, et al. Daratumumab monotherapy in patients with treatment-refractory multiple myeloma (SIRIUS): an open-label, randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2016;387:1551-1560.