The World Health Organization’s pain ladder for cancer recommends opioids for the treatment of moderate-to-severe pain in patients with cancer,1 and is a mainstay of cancer pain therapy. Because of widespread opioid use in patients with cancer, opioid-induced bowel dysfunction is a common concern in this patient population, for whom constipation is the most frequent issue.2 In addition, possible causes of constipation for patients with cancer are often multifactorial, and may significantly affect patients’ quality of life. Assessment of bowel function is therefore important for all patients with cancer.

The prevalence of constipation is reportedly as high as 84% in hospice patients, and 100% in patients with cancer.3 The prevalence ranges from 25% to 100%, depending on the study cited, patient population, and site of observation.3-5

The causes of constipation can be divided into primary, secondary, and iatrogenic sources, and include administration of drugs (eg, opioids, vinca alkaloids, and antiemetics), decreased fluid or fiber intake, decreased exercise, electrolyte imbalances, or location of a tumor.6

Constipation is defined as a decrease in the frequency of passage of formed stools and is characterized by stools that are hard and difficult to pass.6 Reported symptoms of bowel dysfunction may also include bloating, nausea, straining, and a sensation of blockage. Causes, symptoms, and risk factors for the individual patient may overlap and be difficult to identify with certainty. Patients with cancer are often prescribed several medications that can cause constipation, such as antidepressants, antiemetics, opioids, and chemotherapy.

Constipation should be an anticipated side effect of opioid pain management. Opiates delay gastric emptying and stool transit via mechanisms that are driven by central and peripheral opioid receptors.6 The effect of opiates on bowel function is direct and related to the dose of the drug. Tolerance to this side effect, unlike some other side effects associated with opioids, does not develop.2

Complications of unresolved constipation include fecal impaction, bowel obstruction, nausea and vomiting, medication malabsorption, urinary retention, and incontinence.4 In addition, quality of life—a very important parameter for care outcomes in patients with cancer—can be adversely affected. One analysis found that constipation led to irrational thoughts and educational needs, as well as psychological distress; it also affected a patient’s decision to take opioid analgesics.5 Constipation may also lead to an increased number of days missed at work, visits to physicians, and a decrease in health-related quality of life.7

Major oncology groups address constipation, including the Quality Oncology Practice Initiative (QOPI). QOPI’s measures are used to assess quality of care for oncology practices, and the group recommends assessment of bowel dysfunction.8 Specifically, QOPI recommends that “constipation be assessed at the time of narcotic prescription or following visit.”8

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) addresses opioid-induced constipation in at least 2 of its supportive care guidelines, including the guidelines for adult cancer pain,2 and the guidelines for palliative care.9 The NCCN guidelines for adult cancer pain state that preventing constipation is a key to pain treatment efficacy.2 The guidelines also recommend that prophylactic measures include a stimulant laxative (eg, sennosides, 2 tablets every morning), with or without a stool softener.2

The guideline recommendations from the NCCN and QOPI were the basis for our quality improvement project at our institution, and the focus of our primary and secondary objectives outlined in our study.

Studies have found that constipation is rarely documented among patients with cancer, despite the high prevalence reported by patients, and that it is among the supportive care concerns that are least likely to be documented.3,10 Constipation is often underassessed and undertreated, potentially leaving patients to manage their constipation alone, without understanding of the best available treatment strategies. Furthermore, patients may not report constipation without direct questioning about that symptom from the provider.

Pharmacist educational interventions may relate to various topics in a hospital- or a clinic-based setting. The effectiveness of these interventions has not been studied in this particular patient population, to our knowledge. A few studies have described educational interventions by pharmacists or by multidisciplinary teams that helped to improve documentation or guideline adherence.11,12

The primary objective of our study was to determine whether a pharmacist-provided educational intervention would improve documentation of the evaluation of bowel function by the clinical staff. A secondary objective was to review the use of laxatives and stool softeners in each group, to determine whether the intervention could improve the use of laxatives over stool softeners.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective medical record chart review of patients with cancer who received treatment in 2 cancer centers located in the same city. The cancer centers are located approximately 20 minutes apart but have separate patient populations. The data were collected from randomly selected charts of 2 separate patient groups: the “before intervention” group included patient charts from January to September 2014, and the “after intervention” group included patient charts from April to July 2015. The total number of patient charts reviewed was 102.

The data collection period for the group before intervention was chosen to eliminate any potential bias by the clinicians, because the quality improvement project concept was introduced in October 2014. The data collection for the after intervention group was timed for the period after the intervention took place in March 2015, and before results were reported to the hospital cancer committee in August 2015.

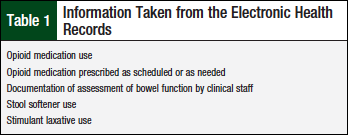

Table 1 lists data taken from the patient medication list in the patient medication record, clinical nursing staff, documentation, and/or physician dictation notes within the electronic health records of before and after intervention patient groups.

Descriptive statistics were used to illustrate the primary and secondary outcome measures. The study was approved by the institutional review board.

Our intervention included an in-service intervention that was provided to the clinical staff once at each of the 2 clinics. The in-service described background information about constipation, including opioid-induced bowel dysfunction, etiology, steps in the assessment process, and the importance of assessing and documenting bowel function in patients with cancer.

The core of the educational intervention included a 30-minute in-service with 4 pharmacy staff members and 9 nursing staff members between the 2 cancer centers, outlining general constipation information, as well as NCCN guideline recommendations.2,9

Two patient handouts were created to serve as reminders of the NCCN guidelines to the entire medical and radiation oncology clinical staff when counseling patients. The first handout details a prophylactic bowel regimen for use at the time opioids are prescribed. The second handout is a home treatment guideline. The 2 handouts were made available via e-mail and shared network drive for easy access, and to facilitate dissemination of the information to the entire staff in both locations.

Results

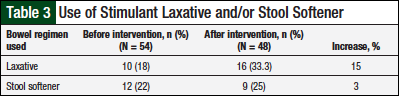

The charts of 54 patients who were prescribed an opioid medication were reviewed before the pharmacist-provided educational intervention. Of the 54 patient charts, 18% (n = 10) included documentation of the use of stimulant laxatives, and 22% (n = 12) included documentation of stool softener use. Overall, 102 charts were reviewed.

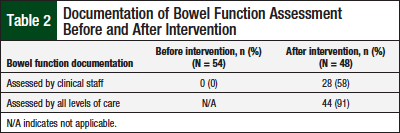

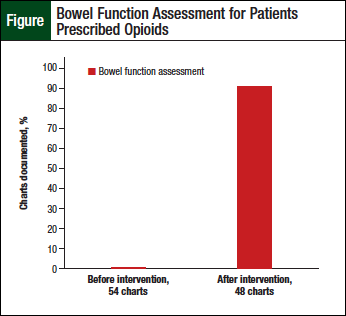

Documentation of the assessment of bowel function by the clinical staff before the intervention was noted to be lacking for all charts reviewed (Table 2). However, improvements were noted in the charts of the additional 48 patients who were prescribed opioids after the educational intervention (Table 3, Figure).

Documentation of stimulant laxative use increased by 15% after the intervention, and documentation of stool softener use increased by 3%, but neither was statistically significant.

Assessment of bowel function by the clinical staff was documented in 58% (n = 28) of the patient charts after the intervention, which was a significant increase (P <.05).

Physician documentation of bowel function assessment, which is typically descriptive in nature, was collected from the patient charts of the 2 groups—before and after intervention groups. Overall, when documentation from all staff were combined (ie, medication lists, clinical staff, and physician), 91% (n = 44) of the 48 charts reviewed after the pharmacist-provided intervention included documentation of assessment of bowel function.

Discussion

The results of this quality improvement project demonstrate that an educational intervention by clinical pharmacists improved adherence to national guidelines at our 2 cancer centers. To our knowledge, this is the first study that assesses whether an educational intervention improves adherence to practice guidelines.

Yam and colleagues demonstrated that a multidisciplinary approach (which included pharmacists and physicians) was used to improve guideline compliance when the researchers initially found poor guideline compliance.11 Reavey and colleagues were able to demonstrate that an educational quality improvement project aimed at educating nursing staff could improve pain assessment in a neonatal intensive care unit.12

Our study adds to this literature in that it provides data that demonstrate improved guideline adherence when a pharmacist-driven educational intervention is provided for the clinical staff. Educational interventions are often provided by pharmacists in the hospital and the outpatient settings, but the outcomes are not always assessed or documented.

Limitations

This study has several limitations, including the small sample size, and being limited to 2 cancer centers within the same city (Lexington, KY). In addition, we were not able to evaluate patient adherence to the bowel regimen that was prescribed or documented.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that a pharmacist-provided educational intervention aimed at increasing awareness of the prevalence of opioid-induced bowel dysfunction in patients with cancer who are receiving opioid therapy for pain can greatly improve the documentation of the assessment of bowel function by the clinical staff. Such an intervention can also increase the use of laxatives and stool softeners for patients with cancer, ultimately improving patient care and increased compliance with current guidelines.

Author Disclosure Statement

Dr Flynn and Dr Gochett have no conflicts of interest to report.

Dr Flynn is Clinical Pharmacist, and Dr Gochett is Oncology Clinical Nurse Specialist, Saint Joseph Cancer Center, Lexington, KY

References

- World Health Organization. Cancer pain ladder for adults. www.who.int/cancer/palliative/painladder/en/. Accessed February 25, 2016.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines): Adult Cancer Pain. Version 2.2014. www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/pain.pdf. Accessed August 1, 2015.

- McMillan SC, Tittle M. A descriptive study of the management of pain and pain-related side effects in a cancer center and a hospice. Hosp J. 1995;10:89-107.

- Reimer K, Hopp M, Zenz M, et al. Meeting the challenges of opioid-induced constipation in chronic pain management-a novel approach. Pharmacology. 2009;8:10-17.

- Dhingra LD, Shuk E, Grossman B, et al. A qualitative study to explore psychological distress and illness burden associated with opioid induced constipation in cancer patients with advanced disease. Palliat Med. 2012;27:447-456.

- McMillan SC. Assessing and managing opiate induced constipation in adults with cancer. Cancer Control. 2004;11(3 suppl):3-9.

- Bell T, Annunziata K, Leslie JB. Opioid induced constipation negatively impacts pain management, productivity, and health related quality of life: findings from the national health and wellness survey. J Opioid Manag. 2009;5:137-144.

- American Society of Clinical Oncology. QOPI Measures & Reporting Pathways - Fall 2017. http://www.instituteforquality.org/sites/instituteforquality.org/files/QOPI%20Fall%202017%20Measures%20and%20Reporting%20Pathways%20-%20Public%20Website.pdf. Accessed January 22, 2018.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines): Palliative Care. Version 1.2016. November 17, 2015. www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/palliative.pdf. Accessed December 22, 2015.

- Nipp RD, Kelley MJ, Williams CD, Kamal AH. Evolution of the quality practice initiative supportive care quality measures portfolio and conformance at a Veterans Affairs medical center. J Oncol Pract. 2013;9:e86-e89.

- Yam FK, Akers WS, Ferraris VA, et al. Interventions to improve guideline compliance following coronary bypass grafting. Surgery. 2006;140:541-547.

- Reavey DA, Haney BM, Atchison L, et al. Improving pain assessment in the NICU: a quality improvement project. Adv Neonatal Care. 2014;14:144-153.