Multidrug regimens have become a staple in oncology, thanks to their ability to overcome multiple areas of treatment resistance by the tumor. The use of multidrug regimens facilitates different mechanisms of attack against the tumor.1 This multidrug regimen method frequently leads to the question of how to sequence chemotherapies or monoclonal antibodies. This is an important question that is asked of oncology pharmacists, because of findings that demonstrate greater toxicity and/or efficacy, depending on the sequencing of the agents.1-5 A common misconception in oncology pharmacy is that these agents have been tested as part of a chemotherapy regimen and are therefore safe and effective, but this belief has been disproved by several studies.2-4

The interaction between cisplatin and paclitaxel is perhaps the most referenced example of this phenomenon of chemotherapy sequencing affecting toxicity.2 The sequence-specific interaction between cisplatin and paclitaxel was documented in 1991.3 When cisplatin is administered before paclitaxel, there is a significant increase in the incidence of neutropenia, which results from a 25% reduction in paclitaxel clearance. By contrast, when paclitaxel is used before cisplatin, there is no such increase in the incidence of neutropenia.3

Another example of this phenomenon has been reported with paclitaxel and cyclophosphamide.4 Profound levels of cytopenias were reported when paclitaxel was infused before cyclophosphamide. When combining chemotherapy in phase 1 and 2 clinical trials, the sequence of these regimens was often not specified, and as was shown with cisplatin and paclitaxel, the sequence can have different or increased side effects for patients.4

When drugs are combined, the rules of pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics still apply. Several chemotherapy agents are extensively metabolized through the cytochrome P450 pathway, and many chemotherapy agents have high degrees of protein binding. When adding the potential for some chemotherapy-specific cell-cycle mechanism of action, it is easy to see how these factors may increase the cytotoxicity, or antagonize the mechanism of action, of the second agent.5 These factors can dictate the order of administration, because of a particular effect or side effect that would be encountered, based on the agent’s pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties. In addition, a chemotherapy agent’s compatibility with different diluents may also affect the chemotherapy regimen’s order of administration.

A previously published review of literature by Mancini and Modlin in 2011 helped shed light on the sequence of the chemotherapy agents approved at that time and helped answer the many drug information questions that are asked in a chemotherapy infusion center.1 Mancini and Modlin compiled available evidence for chemotherapy agents’ sequencing and diluents compatibility through 2009 and created an easily readable chart for real-time use in infusion centers or hospitals.1 However, since then, 18 new intravenous chemotherapy and monoclonal antibodies have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

The purpose of this current review is to update the previously published chemotherapy sequencing chart with the intravenous medications that have been approved since 2010 by the FDA and are used in combination. Because of the number of new intravenous medications that are approved in oncology regularly, the sequencing of agents is constantly changing and needs to be reviewed with the updated information. In addition, this review includes updates on the sequencing and diluent compatibility of agents previously researched during the literature review for the 2011 publication of the article by Mancini and Modlin.1

Methods

First, we collected from the CenterWatch website (www.centerwatch.com) a list of the intravenous chemotherapy and monoclonal antibodies that were approved by the FDA between January 2010 and May 2018. Any agent that was used as a single agent only was excluded from the list. Combination therapy was defined in this current article as FDA-approved regimens only. Then, we compiled a list of agents previously reviewed by Mancini and Modlin,1 with the current FDA-approved combination regimens.

To update the 2011 sequencing chart,1 we evaluated the administration sequence in the original studies in published regimens, when provided in the study. Any chemotherapy agent that is not administered on the same day as another chemotherapy agent per an FDA-approved regimen was excluded from the chart. We reviewed Lexicomp (www.lexi.com) as a standard resource for drug information for the FDA-recommended sequence specifics in the administration and drug interaction sections on that website.6 The clinical trial relating to the FDA approval for each medication and regimen was reviewed to determine if the authors discussed the administration sequence.

Next, we conducted a PubMed search using keywords that included any combination of the drug name and the various combinations with “administration,” “sequencing,” or “interactions.” When evaluating for updated information on the agents listed in the original article by Mancini and Modlin,1 we searched PubMed as well, using the same search terms for these agents, within the date limits of January 2010 to May 2018. After establishing the literature base, we reviewed the studies to determine whether they were clinically applicable, defined as clinical trials that were conducted in humans and that evaluated the forward and reverse sequences of drug administration. Review articles were included if they provided human clinical trial data.

Studies were excluded from the final review if the agents were not recommended for administration on the same day, to keep the consistency with same-day treatment administration at an infusion center. The prescribing information and the online Lexicomp medication database for each newly approved medication were evaluated for the sequence of administration recommendations. If the prescribing information listed a particular sequence but did not elaborate on the reason for this sequence, we contacted the drug’s manufacturer for clarification of the information.

The inclusion and exclusion criteria for this update were selected to mirror the original sequencing article by Mancini and Modlin published in 2011.1 If conflicting data were apparent regarding a sequence after reviewing the study for inclusion, recommendations were made in the chart to err on the side of safety. For example, if one study suggested that a particular sequence was more toxic and a second study suggested that there was no difference between the sequences, the recommendation included on the chart would be that the reverse sequence was less toxic rather than stating that there was no difference in the sequence of the agents.

Finally, we used Lexicomp Solutions’ IV Index with Trissel’s IV Compatibility Tool to assess whether medications were physically compatible via Y-site co-infusion. The Trissel tool was used to match the original article by Mancini and Modlin who used that tool. The medications included the chemotherapy and monoclonal antibodies approved between January 2010 and May 2018 and the agents previously listed by Mancini and Modlin. In addition, base-solution (ie, lactated Ringer’s, normal saline, and dextrose 5% in water) compatibilities for individual chemotherapy agents were evaluated.

Results

A total of 18 intravenous chemotherapy or monoclonal antibodies were approved by the FDA from January 2010 to May 2018 and were approved for use in combination with other agents, including 2 agents that were biosimilars to bevacizumab and trastuzumab. The literature search we conducted on these 18 agents yielded 2 articles for evaluation. Both articles were excluded, because the agents were not administered on the same day. We also conducted a literature search from January 2010 to May 2018 on the previously approved and researched agents included in the 2011 publication, which yielded no new results to suggest any update to the recommendations.1

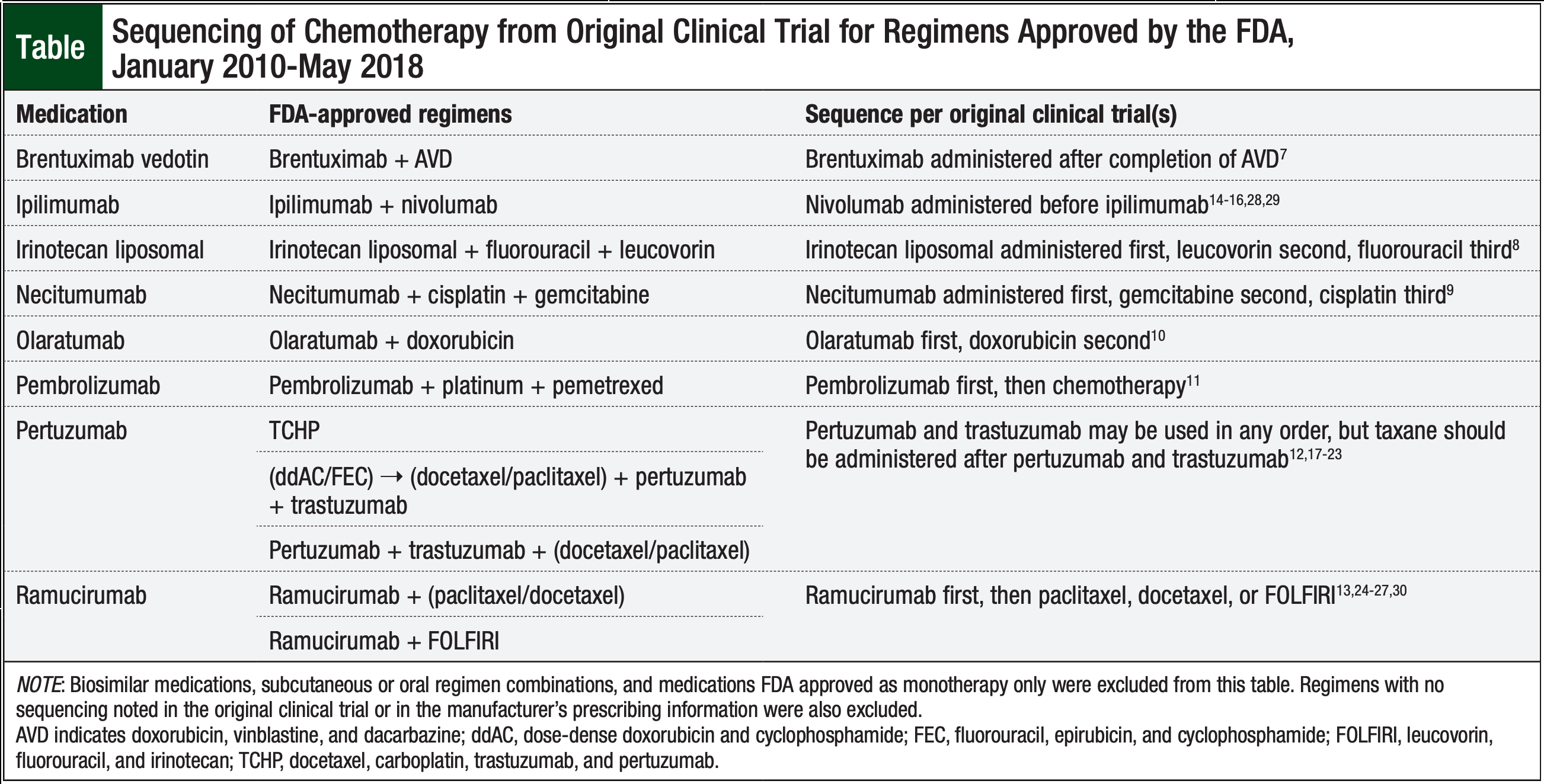

The Table lists the sequencing used in the original clinical trials for 8 of the recently approved medications that were approved by the FDA for use in combination therapies.7-30 The original clinical trials published on the other 10 agents did not specify a sequence of administration in FDA-approved regimens.29,31-44

We updated the original compatibility and sequencing chart (Figure),7,14-44 which was originally published in 2011,1 to include the FDA-approved intravenous chemotherapies from January 2010 to May 2018. These new agents are highlighted in yellow in the chart, including Y-site co-infusion compatibility and base-solution compatibilities. Of the new agents, gemtuzumab ozogamicin was Y-site compatible with daunorubicin and cytarabine. In addition, trabectedin is Y-site compatible with doxorubicin liposomal. Two of the regimens—obinutuzumab plus bendamustine and ramucirumab plus irinotecan and leucovorin—were incompatible because of their base-solution requirements. A total of 11 of the recently approved agents are compatible with a single base-solution.

Several of the recently approved medications had manufacturer recommendations for agent sequencing when administered on the same day. No information was included in the prescribing information for those drugs regarding the reasons for these sequence recommendations. When contacted, the drug manufacturer representatives referred to the original clinical trial(s) involved in the FDA’s approval for sequencing recommendations.

Discussion

The goal of this literature review was to update the user-friendly reference chart published in 2011 that is often used by pharmacists and nurses who work in outpatient infusion centers and on inpatient oncology floors. As stated in the original article by Mancini and Modlin, this chart cannot be used for determining the sequences of chemotherapy agents given over several days, because that was not the original intent of the literature search.1

In this current update, no supportive literature was found regarding the sequencing of the intravenous chemotherapy agents and monoclonal antibodies that were approved by the FDA between January 2010 and May 2018, and no new supportive literature was found for the older agents discussed in the previous publication. While reviewing the literature for the more recent FDA-approved agents, the sequence of administration in the original clinical trial leading to the FDA approval was present in many of the cases, as noted in the Table.

When using the chemotherapy and monoclonal antibody regimens, as long as the sequence is provided in the clinical studies related to the FDA approval of the regimens, institutions should follow the original sequence that appears in those articles.

The question posed in the original article by Mancini and Modlin, “Which drug should be administered first?” still stands today as a common encounter among oncology pharmacists. With continued growth in oncology and an increased number of FDA-approved agents, this question remains important for pharmacists to answer.

The original article by Mancini and Modlin did an excellent job providing a resource that is available in a timely manner to help find the answer to that question and avoid the countless hours that can be spent reviewing the abundance of literature and resources available. Nevertheless, a need remains for solid head-to-head evidence regarding the sequences of intravenous chemotherapy and monoclonal antibody agents in question before further conclusions can be made for the new agents.

Conclusion

The 18 intravenous chemotherapy and monoclonal antibodies that were recently approved by the FDA between January 2010 and May 2018 had no studies discussing forward and reverse sequencing in terms of safety and efficacy, based on inclusion and exclusion criteria required by this article. When not clearly supported by literature that evaluates safety and efficacy, the recommendation for the sequence of administration of combination chemotherapies is to follow the sequence of administration published in the regimen’s original study. The need for further clinical studies is paramount to evaluate the optimal sequence for all combination agents and ultimately to help pharmacists and nurses answer the common question of which drug should be administered first.

Author Disclosure Statement

Dr Lehman and Dr Howard have no conflicts of interest

to report. Dr Mancini is on the Speaker’s Bureau for Millennium

Pharmaceuticals.

References

- Mancini R, Modlin J. Chemotherapy administration sequence: a review of the literature and creation of a sequencing chart. J Hematol Oncol Pharm. 2011;-1:17-25.

- Vaishampayan U, Parchment RE, Jasti BR, Hussain M. Taxanes: an overview of the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Urology. 1999;54(suppl 6A):-22-29.

- Rowinsky EK, Gilbert M, McGuire WP, et al. Sequences of taxol and cisplatin: a phase I and pharmacologic study. J Clin Oncol. 1991;9:1692-1703.

- Kennedy MJ, Zahurak ML, Donehower RC, et al. Sequence-dependent hematological toxicity associated with the 3-hour paclitaxel/cyclophosphamide doublet. Clin Cancer Res. 1998;4:349-356.

- Smorenburg CH, Sparreboom A, Bontebal M, Verweij J. Combination chemotherapy of the taxanes and antimetabolites: its use and limitations. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37:2310-2323.

- Lexicomp. https://online.lexi.com/lco/action/login. (Subscription required to access.) Accessed June 30, 2018.

- Connors JM, Jurczak W, Straus DJ, et al; for the ECHELON-1 Study Group. Brentuximab vedotin with chemotherapy for stage III or IV Hodgkin’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:331-344. Erratum in: N Engl J Med. 2018;378:878.

- Wang-Gillam A, Li CP, Bodoky G, et al; for the NAPOLI-1 Study Group. Nanoliposomal irinotecan with fluorouracil and folinic acid in metastatic pancreatic cancer after previous gemcitabine-based therapy (NAPOLI-1): a global, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2016;387:545-557. Erratum in: Lancet. 2016;387:536.

- Thatcher N, Hirsch FR, Luft AV, et al; for the SQUIRE Investigators. Necitumumab plus gemcitabine and cisplatin versus gemcitabine and cisplatin alone as first-line therapy in patients with stage IV squamous non-small-cell lung cancer (SQUIRE): an open-label, randomised, controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:763-774.

- Tap WD, Jones RL, Van Tine BA, et al. Olaratumab and doxorubicin versus doxorubicin alone for treatment of soft-tissue sarcoma: an open-label phase 1b and randomised phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2016;388:488-497. Erratum in: Lancet. 2016;388:464.

- Langer CJ, Gadgeel SM, Borghaei H, et al; for the KEYNOTE-021 Investigators. Carboplatin and pemetrexed with or without pembrolizumab for advanced, non-squamous, non-small-cell lung cancer: a randomized, phase 2 cohort of the open-label KEYNOTE-021 study. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:1497-1508.

- von Minckwitz G, Procter M, de Azambuja E, et al. Adjuvant pertuzumab and trastuzumab in early HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;-377:122-131. Errata in: N Engl J Med. 2017;377:702; N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1585.

- Obermannová R, Van Cutsem E, Yoshino T, et al. Subgroup analysis in RAISE: a randomized, double-blind phase III study of irinotecan, folinic acid, and 5-fluorouracil (FOLFIRI) plus ramucirumab or placebo in patients with metastatic colorectal carcinoma progression. Ann Oncol. 2016;27:2081-2090.

- Wolchok JD, Kluger H, Callahan MK, et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma.N Engl J Med. 2013;369:122-133.

- Postow MA, Chesney J, Pavlick AC, et al. Nivolumab and ipilimumab versus ipilimumab in untreated melanoma.N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2006-2017.

- Larkin J, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, et al. Combined nivolumab and ipilimumab or monotherapy in untreated melanoma.N Engl J Med. 2015;-373:23-34.

- Baselga J, Cortés J, Kim SB, et al; for the CLEOPATRA Study Group. Pertuzumab plus trastuzumab plus docetaxel for metastatic breast cancer.N Engl J Med. 2012;366:109-119.

- Swain SM, Baselga J, Kim SB, et al; for the CLEOPATRA Study Group. Pertuzumab, trastuzumab, and docetaxel in HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer.N Engl J Med. 2015;372:724-734.

- Gianni L, Pienkowski T, Im YH, et al. Efficacy and safety of neoadjuvant pertuzumab and trastuzumab in women with locally advanced, inflammatory, or early HER2-positive breast cancer (NeoSphere): a randomised multicentre, open-label, phase 2 trial.Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:25-32.

- Schneeweiss A, Chia S, Hickish T, et al. Pertuzumab plus trastuzumab in combination with standard neoadjuvant anthracycline-containing and anthracycline-free chemotherapy regimens in patients with HER2-positive early breast cancer: a randomized phase II cardiac safety study (TRYPHAENA). Ann Oncol. 2013;24:2278-2284.

- Baselga J, Gelmon KA, Verma S, et al. Phase II trial of pertuzumab and trastuzumab in patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive metastatic breast cancer that progressed during prior trastuzumab therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1138-1144.

- Glover ZWK, Gennaro L, Yadav S, et al. Compatibility and stability of pertuzumab and trastuzumab admixtures in i.v. infusion bags for coadministration. J Pharm Sci. 2013;103:794-812.

- Cortés J, Swain SM, Kudaba I, et al. Absence of pharmacokinetic drug-drug interaction of pertuzumab with trastuzumab and docetaxel. Anticancer Drugs. 2013;24:1084-1092.

- Tabernero J, Yoshino T, Cohn AL, et al. Ramucirumab versus placebo in combination with second-line FOLFIRI in patients with metastatic colorectal carcinoma that progressed during or after first-line therapy with bevacizumab, oxaliplatin, and a fluoropyrimidine (RAISE): a randomised, double-blind, multicentre, phase 3 study.Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:499-508. Erratum in:Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:e262.

- Garon EB, Ciuleanu TE, Arrieta O, et al. Ramucirumab plus docetaxel versus placebo plus docetaxel for second-line treatment of stage IV non-small-cell lung cancer after disease progression on platinum-based therapy (REVEL): a multicentre, double-blind, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2014;384:-665-673.

- Wilke H, Muro K, Van Cutsem E, et al; for the RAINBOW Study Group. Ramucirumab plus paclitaxel versus placebo plus paclitaxel in patients with previously treated advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma (RAINBOW): a double-blind, randomised phase 3 trial.Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:1224-1235.

- Chow LQM, Smith DC, Tan AR, et al. Lack of pharmacokinetic drug-drug interaction between ramucirumab and paclitaxel in a phase II study of patients with advanced malignant solid tumors. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2016;-78:433-441.

- Weber JS, Gibney G, Sullivan RJ, et al. Sequential administration of nivolumab and ipilimumab with a planned switch in patients with advanced melanoma (CheckMate 064): an open-label, randomised, phase 2 trial.Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:943-955. Erratum in:Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:953.

- Overman MJ, Lonardi S, Wong KYM, et al. Durable clinical benefit with nivolumab plus ipilimumab in DNA mismatch repair–deficient/microsatellite instability–high metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:773-779.

- Wang D, Braiteh F, Lee JJ, et al. Lack of pharmacokinetic drug–drug interaction between ramucirumab and irinotecan in patients with advanced solid tumors. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2016;78:727-733.

- Sehn LH, Chua NS, Mayer J, et al. Obinutuzumab plus bendamustine versus bendamustine monotherapy in patients with rituximab-refractory indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma (GADOLIN): a randomised, controlled, open-label, multicentre, phase 3 trial.Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:1081-1093.

- Palumbo A, Chanan-Khan A, Weisel K, et al; for the CASTOR Investigators. Daratumumab, bortezomib, and dexamethasone for multiple myeloma.N Engl J Med. 2016;375:754-766.

- Monk BJ, Herzog TJ, Kaye SB, et al. Trabectedin plus pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in recurrent ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3107-3114.

- Blay JY, von Mehren M, Samuels BL, et al. A phase I combination study of trabectedin and doxorubicin in patients with soft tissue sarcoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:6656-6662.

- von Mehren M, Schilder RJ, Cheng JD, et al. A phase I study of the safety and pharmacokinetics of trabectedin in combination with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in patients with advanced malignancies. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:1802-1809.

- Tahir S. Real-life experience using trabectedin plus pegylated liposomal doxorubicin combination to treat patients with relapsed ovarian cancer. EJC Suppl. 2014;12:17-20.

- Colombo N, Hard-Bessard AC, Ferrandina G, et al. Experience with trabectedin + pegylated liposomal doxorubicin for recurrent platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer unsuited to platinum rechallenge. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2016;16(suppl 1):11-19.

- Takahashi N, Li WW, Banerjee D, et al. Sequence-dependent enhancement of cytotoxicity produced by ecteinascidin 743 (ET-743) with doxorubicin or paclitaxel in soft tissue sarcoma cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:3251-3257.

- Leporini C, Patanè M, Saullo F, et al. A comprehensive safety evaluation of trabectedin and drug–drug interactions of trabectedin-based combinations. BioDrugs. 2014;28:499-511.

- Middeldorf I, Galm O, Osieka R, et al. Sequence of administration and methylation of SOCS3 may govern response to gemtuzumab ozogamicin in combination with conventional chemotherapy in patients with refractory or relapsed acute myelogenous leukemia (AML). Am J Hematol. 2010;85:477-481.

- Ravandi F, Estey E, Jones D, et al. Effective treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia with all-trans-retinoic acid, arsenic trioxide, and gemtuzumab ozogamicin. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:504-510.

- Hills RK, Castaigne S, Appelbaum FR, et al. Addition of gemtuzumab ozogamicin to induction chemotherapy in adult patients with acute myeloid leukaemia: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from randomised controlled trials.Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:986-996.

- Marcus R, Davies A, Ando K, et al. Obinutuzumab first-line treatment of follicular lymphoma.N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1331-1344.

- Robak T, Warzocha K, Babu G, et al. Ofatumumab plus fludarabine and cyclophosphamide in relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia: results from the COMPLEMENT 2 trial. Leuk Lymphoma. 2017;58:1084-1093.